How often do we start out to do one thing, with a perfectly

plain and straightforward objective firmly in mind, only to find that

we end up doing something entirely different? This started out as a

simple review. Before I knew where I was "at", Iíd got myself

rather swept up in it all, but by that time it seemed better to go on

than start again! It ended up as what is presented below, a series of

dissertations of such proportions that Iíve had to index it. Follow

the usual web thingy, where you just "click on the link to get

to the bit you want". Maybe youíd prefer to print it out to "read

in bed"? Quite apart from its soporific potential, be warned that

youíll need in excess of 40 A4 sheets. Iím just thankful that Rob asked

me to do the Shostakovich symphonies, and not the complete Haydn set!

Such is the damage that the Soviet regime wreaked that,

even now, much of Shostakovichís history remains contentious. There

is no absolute authority, and I certainly make no claims to be even

a "relative authority", regardless of the (false) impression

endowed by the appearance of my words in print. Hence, even statements

of "fact" that I make are open to argument. My opinions (of

which there are plenty) are my own, and I would welcome argument with

arms open wide. Of course, to argue the toss requires not only you to

have read my "dissertations", but also me to have written

stimulating prose. Thereís only one way to find out. So, off you go

then!

Index

Overture

Symphony No. 1 op. 10 (1926)

Symphony No. 2 op. 14 "To October"

(1927)

Symphony No. 3 op. 20 "First

of May" (1929)

Symphony No. 4 op. 43 (written 1935-6,

f.p. 1961)

Symphony

No. 5 op. 47 (1937)

Symphony

No. 6 op. 54 (1939)

Symphony

No. 7 "Leningrad" op. 60 (1941)

Symphony

No. 8 op. 65 (1943)

Symphony

No. 9 op. 70 (1945)

Symphony

No. 10 op. 93 (1953)

Symphony

No. 11 "The Year 1905" op. 103 (1957)

Symphony

No. 12 "The Year 1917" op. 112 (1961)

Symphony

No. 13 "Babi Yar" op. 113 (1962)

Symphony

No. 14 op. 135 (1969)

Symphony

No. 15 op. 141 (1971)

Round-Up and Conclusions

Overture

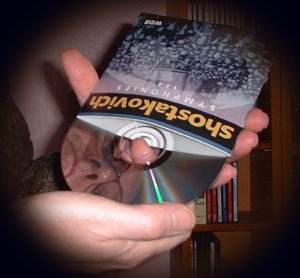

You pays your money and you takes your choice - this

set comes packaged in either standard individual jewel-cases or cardboard

sleeves. My copy is the latter. I rather like it. Itís such a neat little

box. At just under an inch and a quarter thick (a nadge over three centimetres

to the Euro-orientated), it belies the sheer magnitude of its contents.

Just to listen through it a couple of times equates to a full three

daysí work. Alright, it may be far more fun than working, but itís still

a daunting prospect. Itís only now, faced with it myself, that I start

to properly appreciate the sheer effort involved in reviewing complete

cycles. Suddenly humbled, I take off my hat (well, cloth cap) to those

reviewers who scale heights like the Haydn Symphonies, the Mozart Edition

or that Everest of oeuvres, the complete works of J. S. Bach

- and somehow survive to tell the tale.

Shostakovichís symphonies, even in their entirety,

are hardly in the same league when it comes to plain, old-fashioned

bulk. However, in the "salutary experience" stakes, even one

Shostakovich symphony can take some swallowing, to the extent that sitting

down and scoffing the lot in a single, mightily protracted gulp brings

on not indigestion but another hot flush of humility. Letís face it,

even Mahler felt that three hammer blows were enough to finish him off,

so what chance does a mere mortal have when repeatedly thumped in the

ribs through fifteen gruelling rounds?

Sure, Iíve watched the documentaries, and Iíve read

the books (some of them). But working my way through all the symphonies,

one after the other, convinced me with an ear-searing immediacy that

no one symphony on its own can punch home how appallingly fearful Shostakovichís

life was. That he managed to produce anything at all under such conditions

is remarkable, that he produced so much is amazing, and that he somehow

maintained his individuality - along with the wit to express it - under

a regime that habitually murdered individualists simply beggars belief.

Youíd really have to have a heart of stone to listen to these symphonies

from first to last and emerge at the far end entirely unscathed.

This starts to look like it has the makings of a harrowing

write-up. Yet again I am humbled. How would I - or you, for that matter

- have got on, had I (or you) been in his place? "First train to

the salt mines" springs to mind. Yet Shostakovich not only maintained

his marbles intact, but also (and donít ask me how!) managed to hang

on to his sense of humour. Whether wry, ironic, mordant, or uninhibitedly

uproarious, the jester in him is irrepressible: no matter how dire things

became, Shostakovich never seemed to let them get him down for long.

Surely, he must be one of the few truly heroic figures in history, and

prime material for a high-class, big-budget "bio-pic". I sometimes

try to imagine what it would have been like, if Eamonn Andrews had ever

intoned the words "Dmitri Shostakovich, this is yurr loif!"

(especially compared to some of the barely-out-of-nappies dross that

Michael Aspel has to contend with these days).

Mind you, we might reasonably be tempted to ask, "Which

life?" There are at least two versions of the tale (plus more variants

than Iíve had hot dinners). In its simplest terms, this depends largely

on whether or not you believe Solomon Volkovís Testimony. If

you donít, you have to try to extricate the "truth" from the

"official" Soviet history, which is not easy (given that there

are lies, damned lies, statistics, and "official" Soviet history!).

Even now, with both Berlin Wall and USSR dead and buried, and much more

open access to information, we would still seem to be a long way from

the real truth of the matter. The one thing thatís emerging unequivocally

(for now, anyway!) is that Volkovís view is "correct", if

not altogether then at least in principle - and thatís shocking enough

in itself. In what follows, Iím sure it goes without saying that I am

necessarily expressing what I personally have come to believe regarding

Shostakovichís life and motivations. As things stand, the "truth"

is something that we each must decide for ourselves.

Anyway, as I was saying, itís such a neat little box, a decently robust

container for the 11 CDs. Unfortunately, the individual cardboard sleeves

are a little too robust, or rather they are a tad too snug-fitting

- getting a disc out can be a right tussle. Companies especially

please note! The sleeve should be a loose enough fit so that, by

holding it between the fingers and thumb of one hand and gently squidging

it, the disc will slip out edgewise onto the other hand, neatly caught

through the spindle-hole by a middle finger. I soon learnt to immediately

apply the less than ideal remedy of easing each sleeve to give its resident

CD a bit more elbow room. This is a serious complaint, as I found

that the rim of CD3 was marked all around its circumference, rendering

the end of the Sixth Symphonyís middle movement unplayable. I

managed to salvage it, but the procedure - involving diligent polishing

with a very soft cloth and a minute drop of something like "Silvo"

- is hair-raisingly risky even if youíre confident that you know what

youíre doing. Of course, as a consumer you would just demand a replacement,

but then that may be the same! You would in any case be well advised

to store the CDs in their slip-cases "upside down", with the

label side facing the overlapping join in the cardboard. The real point,

though, is that this simply should not be a problem in the first place.

On a brighter note, I give full marks for the very

striking art-work! As is usual, both box and booklet bear the same illustration

but each sleeve, following the same style, bears a different illustration.

The CDs themselves all copy the CD1 sleeve illustration. The 28-page

booklet contains 28 pages of English, believe it or not! I wonder

if copies distributed in (say) Germany are similarly graced with all-German

booklets? I sincerely hope so. Four pages are, quite rightly, devoted

to a profile of Rudolf Barshai, and either one or two pages to each

symphony. The former is by Bernd Feuchtner, the latter by David Doughty

who deftly runs a narrative thread of historical context through his

informative discussions of the symphonies. Now, itís all starting to

look dangerously like a stonking good buy for "newcomers",

so I should advise such folk that prior knowledge is assumed.

This is fair enough: there are lots of leads for the interested to follow

up and, well, we donít want everything dished up on a plate,

pre-chewed or (heaven forbid!) pre-digested, do we?

Even the mildly-initiated will be attracted by the

name of Rudolf Barshai. Heís been around a bit, and in lots of the right

places. A one-time composition student and performing colleague of Shostakovich,

heís perhaps generally best known for his string orchestral arrangement

of the latterís Eighth String Quartet, but between the sheets

of this web site he also gained some reflected notoriety as conductor

of that recording of Mahlerís Fifth, our review of which

caused such a kerfuffle a while back [see http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2001/Apr01/Mahler5.htm

for the review and a supporting article by Norman LeBrecht]. His performing

credentials are substantial right where it counts: creator of the Moscow

Chamber Orchestra, conductor of the first performance of Shostakovichís

Fourteenth Symphony in 1969 and, as a viola-player of considerable

standing, founder member of both the Borodin and Tchaikovsky string

quartets. This chap would seem to be well acquainted with all the necessary

personal onions.

With everything else about the booklet being ship-shape

and Bristol-fashion, itís a shame that a few words about the orchestra

couldnít have been included, seeing as the WDRSO is hardly a household

name. In a sudden fit of altruism, I chased up the WDRSO website to

get some information for you. Itís in German, so I had to resort to

Googleís "translate-a-page" service, whence it becomes my

solemn and bounden duty to pass on to you these priceless gems, verbatim

seeing as I donít think that I dare risk rendering them into colloquial

English. This orchestra "developed 1947 in the northwestGerman

broadcast at that time (NWDR) and belongs today to the West German broadcast",

and "it is not only the Ďhouse orchestraí of the WDR for radio

and television productions, but presents itself also with numerous concerts

in the Cologne Philharmonic Concert Hall and in the whole transmission

area". In addition, "its outstanding call it acquired

itself in co-operation with the principal conductors Christoph of Dohnányi,

Zdenek Macal, Hiroshi Wakasugi, Gary Bertini and Hans Vonk".

I hope youíre following this, because thereís a bit more yet: "as

considerable guest conductors stood as Claudio Abbado, Karl Boehm, Fritz

shrubs, Herbert of Karajan, Erich nuthatch, petrol Klemperer, Lorin

Maazel, Sir André Previn, Zubin Mehta, Sir George Solti and Guenter

wall at the desk of the orchestra". In terms of repertoire,

I should mention that "apart from the care of the classical-romantic

repertoire the WDR Sinfonieorchester Cologne made itself 20 particularly

by its interpretations of the music. Century a name. Luciano Berio,

Hans's Werner Henze, Mauricio Kagel, Krzysztof Penderecki, Igor Strawinskij,

Karl Heinz stick living and Bernd Alois Carpenter belong to the contemporary

composers, who specified their works - to a large extent order compositions

of the WDR - with the WDR Sinfonieorchester Cologne".

Apart from now being all too well aware of the German

for "shrubs", "nuthatch", "petrol" (?),

"stick", "living" and "carpenter", I gather

(or I think I do) that the WDRSO is a top-notch provincial orchestra

on a par with (say) the UKís BBC Philharmonic. My mouth waters at the

prospect: I donít know about you, but I generally find such orchestras

far more exciting than any of the pan-global mega-orchestras. For a

start, they often retain some local "flavour", and being somehow

less exalted and hence nearer the gut-level ground, they seem to be

more attuned to what it means to make real music for real

people, donít you think? Well, in this instance, thatís exactly what

weíre about to find out, so here goes . . .

Symphony No. 1 op. 10 (1926)

Having hit the mat in Maternity only in 1906, Shostakovich

was still in short pants when Lenin and Co. hit the streets in 1917,

and not overlong out of short pants in 1926 when he presented his graduation

thesis for the scrutiny of his professors at the Petrograd (or Leningrad,

or St. Petersburg) Conservatory. Itís hardly overwhelming news that

in this "thesis", his First Symphony, the young Shostakovich

exposes his influences as blatantly as any young lad might his underpants

through torn breeches. They are all there: Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Mahler,

and Glazunov, his teacher at the Conservatory. What is perhaps surprising

is that there is relatively little of Rimsky-Korsakov, who taught both

Glazunov and Prokofiev, and was Stravinskyís mentor. Thatís because,

by the time he wrote this landmark op. 10, the precocious youngster

had already worked his way over that particular hurdle (try Shostakovichís

Scherzo, op. 1, or Theme with Variations op. 3 to be found

on a Melodiya-sourced BMG twofer, cat. no. 74321 59058 2 - shades a-plenty

of Rimsky-Korsakov there!).

What really brings you up short about this music is

not so much the oft-voiced "astonishing accomplishment for one

so young" - as a symphony, itís as short on structural integrity

as it is long on youthful bombast (and thatís not a grumble!)

- but that, like Mahlerís equally youthful Das Klagende Lied,

it already contains all the key elements of his maturity bar

only one, and that is the ability to "carry the line". Not

that we should worry - hereís a burgeoning genius, revelling in a Brave

New World of Cultural Revolution, singing his socks off at the top of

his voice (it would be quite a few years yet, before he had to sing

his socks off to save his life). That itís "not bad for starters"

has been borne out by the musicís enduring, and richly deserved, popularity.

On went CD1. The Moment of Truth. After all the expectation-building,

would my face fall? No, it didnít; instead it was my jaw that dropped.

A clear, bright trumpet, a cuddly bassoon, a clarinet tone to die for!

Oh, and beautifully judged chamber-music textures, clearly etched against

a warm acoustic - and I could hear all the percussion, from the

black bumping of the bass drum right up to the tingle of the triangle.

Doughty points out a Petrushka-like "grotesquerie", but Barshai

finds more than that. Within the confines of a sprightly basic allegretto,

he uncovers a delightful whimsicality interweaving the brash

buffoonery, a perception he carries though to the allegro of

the second movement, where Shostakovich substitutes athleticism for

buffoonery. By the time I got to halfway through the lento third

movement, Barshai had me dubbing this symphony "Ode to Youth".

He laces the throbbing adolescent passion with spoonfuls of syrup that

bring out the tang of bitter lemon in Shostakovichís gauche trumpet-and-snare-drum

fanfare figures. The eruption of the finaleís opening, basses shovelling

the tam-tam up and over, is superbly done. Shostakovich adds to his

brew the impetuosity of a young man, all fired up but as yet with nothing

on which to vent his brimming bellyful of crackling energy, exposed

nerves twitching and pulsing because they havenít quite learnt how to

insulate themselves from the raw stimuli of Life. There may be Stravinsky,

Prokofiev and Mahler looking over his shoulder. Ignore them - this is

Shostakovich, rearing up, kicking at the traces, and raring to

go!

If, in bringing out the youthful buffoonery, zest,

and unbridled passions, Barshai misses a single trick, then I didnít

spot it. His only misjudgement would seem to be the rapid-fire repeated

notes at about 2'17 into the finale, which are that damned quick that

they are smeared into tremolandi, though whether through imprecise

articulation or "saturation" of the warm acoustic itís hard

to say. Yes, every now and then there are little lapses or awkward

corners in the WDRSOís playing, but these are nothing to write home

about, particularly when compared to the spirit of their music-making,

which positively bristles with vitality and (dare I

say it?) commitment. Stunning.

Symphony No. 2 op. 14 "To October" (1927)

A year down the line, Shostakovich was channelling

his creative energies like nobodyís business. In the euphoric years

of cultural revolution the artistic community was humming, like a beehive

in July, with invention and experiment. In those heady days, it was

even OK to exchange ideas with the "West". Shostakovich was

as happy as a pig in muck. In line with the original communist ethos,

there was a great demand for enthusiastic blowing of own trumpets. The

Soviet Union was an unprecedented hotbed of "team-building",

which reached fever-pitch with the imminence of the 10th.

anniversary of the Revolution. Shostakovichís Second Symphony

was, quite simply, written in response to a State commission for a work

to glorify the achievements of the Red Revolution. And why not? Everything

in the garden was rosy!

I wonder why, when the Brits belt out stuff like Rule,

Britannia! or the Yanks, hands on hearts, intone God Bless America,

we call it "patriotism", yet the minute the Reds of Russia

try the self-same thing we call it "political propaganda"

(or, worse, "agitprop")? Smacks of double standards to me.

Along with the Third - and, for that matter, the Seventh,

Eleventh and Twelfth - Shostakovichís Second has

come in for a fair old bit of stick for its "propagandism",

the problem being that along with the propagandist bathwater, the musical

baby has tended to be chucked out. To be perfectly honest (which I usually

am), I think that the Second Symphony is actually a very good

piece of music, lacking only a decent belter of a singable tune for

its choral finale.

Moreover, in sonic terms the largo introduction

is one of Shostakovichís most adventurous passages. Light years off

the beaten track of his otherwise direct style this is an incredible

impressionistic wash of shifting layers of sound. At first, I thought

of the opening of Rheingold, but then - well, although I canít

imagine that Shostakovich would have even heard of Charles Ives, let

alone his music, this sounds for all the world as if it ought to be

called "The Dnieper at Kiev, from Three Places in Little

Russia"! From the black (Dylan Thomas would surely have called

it "bible black") bass drum roll at the start, Barshai builds

a real feeling of oily oppression and creepy-crawly foment, aided by

some deeply rosiny basses.

When the main allegro molto started, I was again

impressed by the sound of the WDRSO, this time particularly by the nut-flavoured

woodwind and some spectacularly raucous brass. Already, Shostakovich

is learning to "carry his line", courtesy of a quasi-fugal

treatment of his materials. Barshai grabs the opportunity with both

hands, moulding out of the embattled confusion a terrific build-up to

a broader climax. With the melodic and harmonic contours veering momentarily

towards Scriabin, this sounds not so much like "We are victorious!"

as "Are we victorious?" Barshai equally coaxes some real Russian

gloom out of the ominous disquiet of the slower central music. The final,

choral section is fired off by a factory siren, apparently "keyed

in F sharp", though how I donít know! This cuts in so alarmingly

that itíll have the family dog running for cover. The WDR chorus sound

full-bodied and pretty idiomatic, standing their end resolutely against

the big orchestra. Only their final words, which are supposed to be

"shouted", sound a bit understated, and frankly Iím a bit

surprised that Barshai didnít put a rocket under them! Chorus versus

Orchestra is never an easy balance to strike, but itís struck superbly

here. Thereíre neither words nor translation given of the poem (by Alexander

Bezymensky), though we are told the gist of it: "Lenin - struggle

- October - the Commune - Lenin", which is probably all we need

to know?

All in all, with some terrifically intense playing,

Barshai and the WDRSO (and Chorus) make out a convincing case for this

symphony, which although it isnít Shostakovichís best is still nowhere

near the unmitigated "crock of s***e" that some folk would

have us believe.

Symphony No. 3 op. 20 "First of May"

(1929)

Having its origins in pre-Christian fertility rites,

the traditional May Day festival celebrates the coming of spring-time

with garlanded processions and maypole dancing. Or at least it does

where it survives - I often wonder why in this day and age we forego

the simple rustic pleasures of innocent little fertility rites. Itís

likely that the festivalís association with "rebirth" or "renewal"

influenced the 1889 International Socialist Congress in its designation

of May Day as an international labour day, which in its turn was adopted

by the Soviets to celebrate their victory over the Tsarist regime. Looked

at this way, the seemingly obscure connection between floral frolics

on the village green and parades of military might in Red Square becomes

crystal clear, doesnít it?

Shostakovich cheerfully opted for the same "one

continuous movement with choral ending" format as he had for the

Second, but adopting otherwise (as you might expect) a lighter,

more festive overall tone. Doughty points out that "again there

is little attempt at true symphonic form", whatever "true"

might mean in relation to such an all-embracing, infinitely flexible

musical model as the Symphony. My feeling is that Shostakovich deliberately

sacrificed the relatively conventional form and much of the melodic

invention of his First Symphony at the altar of colourful and

rhythmic effect, so that he could concentrate on honing his argumentative

techniques - and thatís why the Second and Third symphonies

are generally regarded as the crucibles in which he forged his mature

style. Once heíd cracked that, he would turn his attention - in no uncertain

terms - to the question of symphonic architecture.

Performance-wise, itís much the same tale as before:

right at the outset, the pastoral tone - presumably representing workers

peacefully working - is finely spun (those luscious clarinets again!),

and the ensuing balalaika-like thrumming of strings - presumably representing

workers downing hammers and sickles for the festivities - sounds as

fresh as new paint. The ensuing whirl of merriment seems to go on for

fun-filled ages, and to my ears Barshai never puts a foot wrong, even

by the merest whisker. The playing of the WDRSO is vivid and alive in

every bar, trumpets and horns in particular having a whale of a time.

Towards the end of this allegro, thereís a comical passage for

woodwind (shades of the composerís contemporary The Age of Gold)

which is deliciously done.

The allegro struts off into the distance, leaving

behind what I imagine as nocturnal, vodka-induced hallucination: eerily

groping high strings are punctuated by íecky thumps from drums and brass,

and ghostly dancing veers from weird to wonderful by way of whacky -

and thatís exactly how itís played! Come the "dawn", and the

shenanigans resumes, this time firmly in "Keystone Kops" territory

with Barshai deftly choreographing the orchestraís frenetic antics.

Artfully vaulting from Shostakovichís "chase" to "riding"

mode, the conductor displays an almost equestrian proficiency, steering

his surging stallion with a nudge of the heels here and a tug on the

reins there. A big, bold climax triggers a drum roll over which jut

jagged unison phrases (the birth of another Shostakovich trademark?).

Shuddering basses, miry tuba, sonorous tam-tam, slithering strings conspire

to lecture us on the bad old days - the cue for the chorus to make resonant

pronouncements about "hoisting flags in the sun", and marching

sturdily into a (sadly) fairly commonplace conclusion.

Good music, or bad music? Maybe here thatís not the

question. Good performance or bad? Ah, that is the question!

This orchestra may not have been born to play Shostakovich, but by golly

it sounds like it. That is I suspect all due to Mr. Barshai, who leaves

no stop un-pulled.

Symphony No. 4 op. 43 (written 1935-6, f.p. 1961)

Try to imagine what it would be like to sit down to

breakfast one sun-soaked morning, basking in both sun and successful

career, open the paper, and read that in your absence you have been

tried and condemned for a crime that wasnít even considered naughty

when you did it. Worse, the "crime" is the very reason that

you are successful and much admired by your peers. Bemused, you set

off for work, only to see posters publicly displayed declaring you to

be an "enemy of the people". A scenario so horrific and grotesque

could only have come from Kafka, couldnít it? Yet, this is precisely

how Shostakovichís honeymoon with the Soviet state ended - "in

tears" doesnít even begin to describe it.

The cause of all the fuss was not the Fourth Symphony

(though had he got it out sooner, it might well have been), but what

was his first really serious composition, the opera Lady MacBeth

of the Mtsensk District, which contains many of the elements that

opera fans the world over have come to know and love - humiliation,

violent sexual harassment, lust, jealousy, rape, whipping, murder by

rat-poison, adultery, murder by strangulation and beating, drunkenness,

bullying, murder by drowning, suicide by drowning. All good, clean fun?

Not to the politically correct Mr. J. Stalin and his cohorts. Deciding

that they knew what was best for the USSR, they undertook some draconian

measures of ensuring that everyone followed their advice.

In a way, Shostakovich was lucky: while Meyerhold,

the producer of Lady Mac., was "taken out" in 1940,

Shostakovich survived - by keeping his head well down. Nape-tinglingly

aware that the music of the Fourth Symphony had a distinct family

resemblance to that of the opera, he withdrew it. There are two consequences

that are usually glossed over. Firstly, regardless of anything else

(like his skin), it must have hurt him like hell; the Fourth

was his first unequivocally "great" symphony, a massive work

of Mahlerian proportions over which he must have sweated blood. Secondly,

in spite of the enraged bitterness of much of the music, this is still

the product of that "honeymoon", and no matter how much it

sounds like it ought to, there is no trace of the musical "subversion"

that was to come. Thirdly ("NOBODY expects the Spanish Inquisition!"),

that in itself begs the question, "So what was the cause

of all that enraged bitterness?" Now, that is the question

- please write your answers on £5 notes and send to me c/o Musicweb!

Or. so I thought. Another version of the tale has it

that Shostakovich became aware of the beginnings of Stalinís first "Purge",

which began in the confines of government and only gradually spread

outwards, in the last few months of working on the Fourth. He

wouldnít feel the lash personally until the Lady Mac. debacle

a few months after finishing the symphony, and although too late to

influence the content of the symphony overall, it is likely that this

awareness may have moved him to "tailor" its ending to reflect

his feelings. If so, then this lends to the closing pages of the work

a certain political significance that marks the beginning of his "career"

(see Thirteenth Symphony!) as a musical subversive.

The Fourth Symphonyís first movement alone lasts

as long as the whole of any of the first three symphonies, yet

is so packed with extreme invention that its doesnít seem like it -

provided, that is, the conductor knows what heís about. Doughty refers

to the workís "sprawling undisciplined mass of ideas" Hum.

Granted, it is episodic, but the episodes do have a definite connective

logic, and if this is not managed properly - preferably with an iron

fist in a velvet glove - the whole thing does indeed rapidly deliquesce

into a messy puddle on the floor.

Without going into detailed comparisons, I think I

can safely say that Rudolf Barshai has given us a performance of this

movement which can hold its head up in all but the most exalted company.

His one misjudgement is not artistic but practical: the hurricane-force

string-led fugue towards the end of the "development" is too

fast - not for the players, who rip into it with gob-smacking venom,

but simply because the acoustic and/or the microphones canít comfortably

resolve the seething cascades of notes! Admittedly, the players are

clawing at (or maybe even a bit beyond) the limits of their capabilities,

and the ensemble is thus a bit scrappy, but it doesnít half get you

onto the edge of your seat. That aside, with nary a tempo or tempo change

that feels "forced", Barshaiís grip on the proceedings is

iron-fistedly phenomenal but never, as befits a velvet glove, glaringly

obvious.

Mind you, within this disciplined framework, the orchestraís

playing is as overheated as you could wish. The WDRSO players, as witness

the above-mentioned string fugue, may not have the scalpel-bladed precision

of Ormandyís Philadelphians, but they more than make up for it with

some truly gut-wrenching violence and finely-drawn bemused and desolate

interstices, leaving you with the feeling that perhaps the most staggering

thing about this movement is that Shostakovich had the gall to mark

it simply allegretto poco moderato. "Allegretto"

indeed - who does he think heís kidding?

Significantly, the second movement is cast in that

sine qua non of simple layouts, extended binary form, and its

main subject bound by that most rigorous of compositional processes,

the fugue. It wears its badge of allegiance to the Mahlerian Landler

with justifiable pride. Barshai resolves the apparent conflict between

moderato and the qualifying con moto to produce a dancing

interlude that combines rustic delicacy and rumbustiousness, troubled

only as the end of each main section approaches by surges of repressed

bile. Barshai brings out a feeling that the composer was, for some reason

best known to himself, gipping on his own sweet-meats. The players respond

with evident affection, and the sheer sound that they make is a joy

to hear - especially in the "tick-tock" percussion coda, recorded

with crystal clarity, with its gently tramping basses, whirring violins,

and delectable flute fluttertonguing.

The imposing canvas of the third and final movement

is a more satisfying symphonic experience than either of the previous

symphonies. Doughty suggests that it is in five sections - which we

might call "Funeral March", "Allegro", "Waltz",

"Scherzo" and "Peroration and Coda" - but doesnít

add that the "Scherzo" is embedded within the "Waltz",

an important contributor to the movementís symmetry and complementarity.

Yet again, Barshaiís grasp of the musicís logic is impressive. Refusing

to confuse the initial largo marking with adagio, he imposes

a consistent onward flow and builds the pressure inexorably. The WDRSO

respond by punching home the climax with doom-laden ferocity. In the

sharply-etched "allegro", Barshai skilfully graduates the

several ostinati, with one exception which he presents with rigid,

maddening monotony: this ostinato, or its twin brother, will

return to madden us again in the Eighth Symphony! If that were

not enough, the ensuing build-up and climax are a distinct pre-echo

of the finale of the Seventh.

In my book, nobody ever puts across the witty surrealism

of the bibulous "Waltz" with quite the same style as Gennadi

Roszdestvensky (heard live), though whether youíd want to live with

his extreme exaggerations on CD is quite another matter. Veering, albeit

less vertiginously, between ballroom and fairground, Barshaiís must

surely be some sort of golden mean, coaxing some leery playing with

(I would guess) a round of carefully measured tots of vodka - possibly

confirmed by the increasingly hectic scramble of the "Scherzo".

The WDRSO blast out the "Peroration" to literally

terrible effect, the two sets of antiphonally-placed tympani thundering

murderously if with less than ideal precision - but at least the tymps.

are antiphonally divided, unlike several other recordings (including

Ormandyís). I must admit that I prefer a tempo more like Haitinkís,

with more majestic air around the angular figurations. Or at least I

thought I did, until now: Barshaiís faster pulse sets the music thrashing

about in a fit of furious rage. That may not only be equally valid,

but also make a telling point out of what is generally just a passing

observation.

The observation is that the wittering string ostinato,

emerging from the tail end of the "Waltz", is a dead ringer

for an effect in the third movement of Mahlerís Second. Alright,

maybe lots of us know that already, but then consider the "Waltz/scherzo"

from which it emerges. Doesnít this equally parallel Mahlerís expressed

commentary on the banalities and trivia of life? If so, then it follows

(with impeccable logic!) that Shostakovichís "Peroration"

is his equivalent of Mahlerís "Cry of Disgust". This would

account nicely for Barshaiís furioso frazzlemente approach. The

thing is, once you accept that much, you start to wonder about parallels

between Mahlerís and Shostakovichís first two movements (go on, you

do it!). The conclusion, and the reason for all Shostakovichís anger

(growing political awareness apart), might be that he is finally fed

up to the back teeth with writing nothing but shed-loads of relatively

trivial "gee up, folks, and letís have fun" music.

The symphony would thus appear to be a declaration of the motivations

hiding behind Lady MacBethís skirts. The anguish of that public

pillorying must have been privately doubled by having to choke this

symphony at birth. That we can today enjoy the privilege of listening

to it must, appropriately and retrospectively, make it Shostakovichís

Resurrection Symphony - a delicious irony!

How ironic then that it should end, not in triumphant

affirmation, but inconclusive ethereal musing. The WDRSOís gruff basses,

unearthly woodwind, silken string lines, and liquid celeste all pulsing

and shining as if from some realm a million miles away. Shostakovich,

like Arthur C. Clarkeís Star-Child, is "not sure what he would

do next, but he would think of something".

Part

2

Part

3