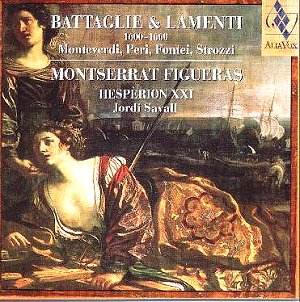

Battaglie & Lamenti: 17th Century music for battles and

lamentation

Samuel SCHEIDT

(1587-1654)

Pavan (1621)

Galliard Battaglia (1621)

Claudio MONTEVERDI

((1567-1643)

Lamento d'Arianna: Lasciatemi morire

(1608)

Giovanni GABRIELI (ca.

1554-1612)

Canzon III a 6. (1621)

Bastiano CHILESE (fl.

1608)

Canzon in Echo a 8 (1608)

Jacopo PERI (1561-1633)

Lamento di Iole (1628)

Luigi ROSSI (1598-1653)

Fantasia "Les Pleurs d'Orphée2

(1630)

Nicolò FONTEI (ca. 1600-ca.

1647)

Pianto d'Erinna

(1639)

ANONYME

Sarabande Italienne, (ca. 1650)

Barbara STROZZI (1619-1664)

Il Lamento "Su'l Rodano severo"

(1634)

Andrea FALCONIERO (ca.

1585-1656)

Battaglia de Barabasso yerno de Satanas

(1650)

Montserrat Figueras

(soprano)

Montserrat Figueras

(soprano)

Ton Koopman (clavecin); Rolf Lislevand (théorbe); Robert Clancy

(théorbe)

Jordi Savall (basse de viol); Paolo Pandolfo (basse de viol);

Lorenz Duftschmid (violone)

Hespèrion XXI/Jordi

Savall

ALIAVOX AV 9815

[76:12]

ALIAVOX AV 9815

[76:12]

Crotchet

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Battaglia and lamento are two genres that cover the whole range

of musical expression in both the vocal and instrumental music of the

17th century. Battaglia covers the din of battle, soldiers

spurred by the rhythm of drums and the sound of trumpets while the lamento

covers the personal anguish of individuals or whole nations trapped in

a hopeless situation. The origins of the battaglia can be traced to

the beginning of the 16th century; the earliest lamenti

were composed before the end of the 16th and the beginning of

the 17th centuries. In fact it was in 1528 that Clément

Janequin's chanson La guerre that set the model for future musical

battaglie. The works in this collection are a fine representative

selection of both genres.

I have often praised Jordi Savall's direction of Renaissance and Early Baroque

music. His earlier recordings for Alia Vox have been remarkable for their

scholarship, lucidity and vitality. This latest album is no exception. The

numbers associated with battles are colourful and lively. The programme commences

with the Pavan and Galliard Battaglia of Samuel Scheidt. Rather

appropriately, the Pavan gives the impression of a mix of lamentation and

celebration; there is the formality of strict drumbeats both in a doleful

funeral procession mode, and in the urge to battle; and there is music in

a more celebratory mood. In fact, one might imagine this music as dance music

too, like the material in some parts of the Galliard when war-like bugles

are not sounding. (After all, in musical dictionaries, Galliard is defined

as a "lively dance from 15th century or earlier in simple triple

time"). Additionally, we have the lively and celebratory Canzon's of Giovanni

Gabrielli and Bastiano Chilese which must have sounded magnificent in the

acoustic possibilities offered by, for instance, St Mark's cathedral, Venice

- particularly Chilese's Canzon in Echo with its near and distant

canonic echoes adding so much more interest. Guami's Canzon sopra la

Battaglia is somewhat relaxed, the fray somewhat gentlemanly and elegant,

one imagines. Not so the final number, Andrea Falconiero's energetic

Battaglia de Barabasso yerno de Satanas. This is exciting indeed and

must have spurred the troops with its biting pizzicatos and thrilling overlapping

brass imperatives.

There are two other purely instrumental numbers: Luigi Rossi's beautifully

mournful Fantasia "Les Pleurs d'Orphée" and the dainty dance rhythms

of the Anonymous Sarabande Italienne.

The most extended numbers in the programme are the laments, sung very

expressively and with great passion by Montserrat Figueras (most beautifully

accompanied, especially by Ton Koopman). Ms. Figueras's dark-hued and smoky

voice is ideal for such material where most of the lines lie in the soprano's

lower registers and she loses no opportunity to express the wide range of

emotions expressed by her hapless heroines: grief, anger, hurt pride, impatience,

spite and yearning. She begins expressing Arianna's (Ariadne) grief at being

abandoned on a desert island by Theseus before Bacchus will deliver her,

in Claudio Monteverdi's Lamento d'Arianna, the work which really founded

the musical genre of the lamento. It is a highly expressive recitative of

such emotional intensity that it reduced the audience to tears. Arianna's

lament mounts to an almost hysterical frenzy as she invokes all the terrors

of the seas, sharks, whales and storms to avenge her before she droops down

again in resignation. Jacopo Peri's Lamento di Iole is very much in

the same mould, except that this time it is Iole grieving for Hercules abandoning

her for the glory of the wars, leaving her to gnash her teeth and agonise

imagining her hero disporting in the arms of others. The lament was also

used in a more universal capacity to deplore certain political events like

the fall of Constantinople, the death of a sovereign, the defeat of a general,

or oppression by some foreign power. Unusual in two ways, is Barbara Strozzi's

lurid and melodramatic Il Lamento, "Su'l Rodano severo" because, of

course, it is written by a woman (in an age when so few women were heard)

and secondly its theme is not thwarted romance but political tragedy. The

singer mourns the downfall and death of Henri Cinq-Mars, the favourite of

King Louis XIII, who was first protected then cast aside by Cardinal de

Richelieu.

The packaging and presentation is first class. Another feather in the cap

for Jordi Savall and his players.

Ian Lace