BRAHMS:

Symphony No 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Variations on the St Anthony

Chorale

Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester Leipzig/Hermann Abendroth

Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester Leipzig/Hermann Abendroth

recorded 1949

BERLIN CLASSICS

0092432BC Mono [63.49]

BERLIN CLASSICS

0092432BC Mono [63.49]

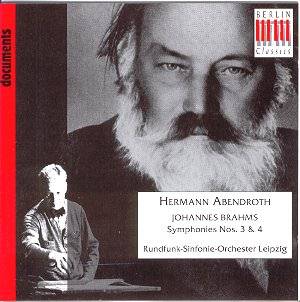

Symphony No 3 in F minor Op. 90

Symphony No 4 in E minor

Op.98

Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester Leipzig/Hermann Abendroth

Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester Leipzig/Hermann Abendroth

recorded 1952 (Op.90), 1954

(Op.98)

BERLIN CLASSICS

0094332BC Mono [71.38]

BERLIN CLASSICS

0094332BC Mono [71.38]

The great regret about the first of these CDs is the poor recording quality.

Underneath a very muddy sound (the opening timpani strokes in the First Symphony

are almost completely inaudible through speakers, but not headphones) lies

a performance of considerable fire and abandon. Any listener interested in

acquiring a great performance of Brahms' C minor symphony should persevere

with this disc for immured within it is a Brahms interpretation it was once

the norm to hear. Here we have a performance that is unbuttoned in its passion

- and, most unexpectedly for this conductor in Brahms, profoundly lyrical.

Listen to the horn in the first movement, or the solo flute and clarinet

in the second and you will be astonished by the refinement of the playing.

It is as if each of these is a lone voice. As always with Abendroth the pacing

is brisk and matter-of-fact, his use of rubato less common than with his

contemporaries.

Among other things, Abendroth's Brahms is so successful because he constantly

alludes to the precision of the composer's notation and orchestration. The

performance of the First Symphony is far from the turgid, over-laden indulgence

we so often encounter in performance (see my

review of Thomas Sanderling's

Philharmonia cycle for a comparison of how not to play Brahms). Here we have

playing that takes account of rhythm and metre, and, more importantly, takes

account of intonation. True, there are problems with some of the playing

(though not the horns or woodwind which are constantly a delight to the ear)

but this is of little concern when the end result emerges so compellingly.

The nobility of the opening tutti is an example in point - with timpani strokes

(from what I can detect) being exactly as Brahms demanded, taken in tempo

and dynamically at f not ff as is so often the case. Elsewhere

Abendroth achieves a miraculous balance of orchestration with woodwind and

strings for once in harmony. If the final movement contains the most extreme

examples of Abendroth's subtle use of rubato - with strings often pushed

to the limit - it is balanced by the knowledge that the last 14 bars are

played with astonishing fidelity to the text. Here the rising bass line is

perfectly audible beside restrained timpani. This remains one of the finest

Brahms Firsts available.

The Third Symphony is one of the most difficult to bring off in performance

- its mood of introspection and romanticism a problem for many conductors.

Toscanini only succeeded once on disc in giving a great performance of this

symphony (his account with the Philharmonia on Testament) and Abendroth's

performance measures up to that recording well. Abendroth's objective approach

to Brahms' orchestration is probably the antithesis of what this symphony

needs yet in the first movement Abendroth seems to find the a range of

expressivity (listen from 8'10 to 8'26) which contrasts nicely with the

turbulence elsewhere in this movement. The mood of solemnity in the pastoral-like

second movement is most successfully done from the very opening dialogue

between clarinets and low strings to the descending cellos and basses which

close the movement in stillness and tranquillity. The allegretto's

melodious cadences, with superbly poetic cellos and deft touches elsewhere,

are as impressionistic as on any performance I can recall. When we come to

the finale, with its turbulent change of moods and direction, we really find

conductors encountering all sorts of problems (notably Furtwängler who

never quite got this movement right). Not so Abendroth. Everything here is

as it should be - the articulation of the proto fugato is astonishing in

its demonic power, the entry of C minor a veritable tempest of activity.

Woodwind are securely fleet, strings impassioned in the furious descending

scales - everything neatly in place but without the slightest hint of

over-preparation. The ending - sublime in its peacefulness and restiveness

- is here beautifully phrased by the violins floating towards the stillness

like falling snow. It closes a revelatory performance.

Brahms' last symphony has received many great performances and Hermann

Abendroth's joins them. Abendroth is the very antithesis of Wilhelm

Furtwängler in virtually everything that he conducted but in this symphony

the comparisons between the two are strikingly similar. Both brought considerable

drive to the first and last movement codas, and both achieve heights of poetry

and inspiration that elude most other interpreters of this great work. What

strikes me most about this performance is the extraordinary tenseness Abendroth

builds up almost from the very first bar. Indeed, the very opening phrases

are built up with the sole purpose of making this a tragic performance of

a tragic work. Any number of moments from this astonishingly wild and abandoned

performance would illustrate its greatness but I will concentrate on just

two. The first is the opening of the second movement. This whole movement

is a masterful combination of wondrous poetry and Brahmsian impressionism

with the very opening, until its transition to the main theme, being one

of the utmost lyricism and beauty. Here Abendroth is unsurpassed giving a

fugal, organ-like sonority to the instrumentation. The entry of the clarinets

and first bassoon (almost as a trio) are magically played as written -

pp - almost so that their inaudibility is achieved (this is, I imagine,

as it would sound in the concert hall). The rest of this opening development

requires enormous balance (as well as technical control from the players)

with horns in particular playing as written and not drowning out the underlying

melody. Largely, Abendroth achieves this.

The final movement of the Fourth Symphony is a unique movement being a set

of variations. Moving from variation 21 (a volcanic outburst of staggering

energy) to the final variation (No.30) Abendroth's performance has a drive

of Aeschylean breadth and majesty. Listen to his handling of the horn and

first violins variation (No.23), the marcato triplets (on flutes and

violins) in the next two variations or the rapid poco ritard of the

final variation's close and you will experience a subliminal power rarely

encountered in this symphony. Over and over again there is a fidelity to

the text most conductors miss. It concludes another great performance.

Both of these discs offer Brahms interpretation of the highest stature. Although

the sound requires some tolerance (considerable tolerance in the First Symphony)

they are unforgettable performances. The orchestral playing is largely first

class and always totally committed. They are quite fascinating historical

documents of one of the last century's greatest, yet most undervalued,

conductors.

Marc Bridle

See also Rob Barnett's review

of the second disc

ORDERING AND ENQUIRIES:-

EdelClassics

EDEL/Berlin Classics discs CANNOT yet be ordered directly from the

website. However it is probably worth browsing anyway:

You can try:-

EDEL affiliates in UK and USA:

edel UK ltd.

12, Oval Road

NW1 7DH London

phone: 0044 207 48 24 848

fax: 0044 207 48 24 846

edel America Records, Inc.

1790 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, NY 10019

phone: 001 212 5419700

fax: 001 212 6648391