It was more than 30 years ago that I first heard the music of Sergei Bortkiewicz,

played by Moritz Rosenthal. It was the Etude, Op. 15, No. 8 and it

absolutely enthralled me with its sweeping melody and great climaxes. I wanted

to search out more of his gorgeous music, to play it myself. It was then

than I realized that this was no easy task. Sergei Bortkiewicz was a composer

relegated to the obscure back rooms of music's Hall of Fame and his major

piano scores were no longer in print. In fact it took me more than 20 years

to acquire most of his compositions for solo piano.

Such a situation really intrigued me. How was it that a composer born in

the 19th century, a contemporary of Scriabin, Rachmaninov, Glazounov and

others, who outlived all of them and died in 1952, should be forgotten so

completely? He lived into the age of stereo recording and yet not a single

example of his piano playing is available. He was a Russian, and no mention

is made of him in books on music published in Russia.

It was only after I got a copy of his autobiographical sketches, "Erinerrungen"

(Recollections), published in 1971 that I was able to understand partially,

Bortkiewicz's character and Weltanschauung. These recollections, at times

whimsical and amusing but never dull, also explain to a certain extent the

oblivion into which he has been relegated.

Sergei Eduardovich Bortkiewicz, was born in Kharkov in 1877 in a wealthy

family of land-owners. He spent a happy childhood in the family estate of

Artiomowka, about 24 kilometers from Kharkov, and showed an early interest

in music. At the insistence of his father, after finishing his schooling,

he left for St. Petersburg and enrolled in the Faculty of Law, as well as

the Imperial Conservatory of Music.

The Petersburg Conservatory at that time was held in high regard and counted

professors such as Rimsky-Korsakov, Liadov, Glazounov, and Blumenfeld on

its teaching staff. It was there that Bortkiewicz received his musical training,

while at the same time trying to study law.

For three years he dutifully undertook his law examinations, but never completed

his fourth year and decided to leave the University so as to proceed abroad

for further musical studies. But before that he had to complete one year

of compulsory military service so that the authorities would issue him a

passport to travel abroad.

Indeed, it was one of his great desires from early youth. He especially wanted

to go to Germany, the land of Goethe and Wagner, where he thought he could

discover wider horizons, and get a more thorough education.

So in the fall of 1899 he started his military service in St. Petersburg,

but soon developed a lung inflammation due to the rigorous military life

and was discharged from military service because of poor health. Early next

year he left Petersburg for good and travelled to Leipzig, where he became

a student of Alfred Reisenauer, who had been one of the favored students

of the legendary Liszt. Bortkiewicz, in turn, was one of the favorites of

Reisenauer, and it is to him that he dedicated his splendid set of Etudes,

Op. 15. It is with reluctance that he describes Reisenauer's alcoholism and

his early death due to a heart attack at the age of 43, brought about by

alcohol addiction.

After his first year of musical studies, Bortkiewicz spent the summer in

Italy, learning Italian and giving concerts. He returned to Leipzig, studying

assiduously, attending many concerts and was much impressed by the conducting

of Arthur Nikisch. Years later, the conductor was enthusiastic about

Bortkiewicz's Piano Concerto, No. 1, Op. 16 and strongly recommended its

publication.

In July 1902, Bortkiewicz completed his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory,

and was awarded the Schumann Prize. That summer he returned to Russia and

to the family estate of Artiomowka where he met his future wife, Elisabeth

Geraklitowa.

He gave concerts in Kharkov and also played with the symphony orchestra of

the city. In July 1904, he married Elisabeth and traveled back to Germany,

where he settled down in Berlin. It was only after marriage that he started

composing seriously. His first publisher was Daniel Rahter of Leipzig, who

unfortunately died early; the firm was subsequently taken over by A.S. Benjamin.

From 1904 till 1914, Bortkiewicz lived in Berlin, spending his summers in

Russia, or traveling over Europe. For a year he also taught at the

Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory, but left it after some unpleasant

experiences. He then took to concertizing not only in Germany, but also in

Vienna, Budapest, Italy, Paris and Russia. However, the career of a virtuoso

did not appeal to him and he concentrated instead on composition and teaching.

His Etudes, Op. 15 had just been published by D. Rahter when he was in Berlin,

and it was there that he found a lifelong friend in Hugo van Dalen, the Dutch

pianist and composer (1888-1967). Dalen told him that it was through his

playing of the Etude Op. 15, No. 8 that he had met his wife. She liked the

piece so much that she came up to van Dalen to ask the composer's name. This

acquaintance led to their marriage, as a result of which Bortkiewicz unofficially

named this etude the "Verlobungsetude" (Betrothal etude).

The outbreak of the war in 1914 shattered Bortkiewicz's life. Being a Russian

alien in Germany he was suspected of being a spy and placed under house arrest.

After 6 weeks he was allowed to leave for Russia through Sweden and Finland.

He established himself in Kharkov as a music teacher, at the same time giving

concerts in Orel and Moscow, where he met Scriabin, whose music he much admired.

He describes Scriabin as a slightly built man, with an upturned moustache.

"Just imagine Chopin or Raphael with a moustache à la Wilhelm II!"

he writes mischievously.

The situation took a turn for the worse in 1917 with the collapse of the

Russian army. There was chaos in southern Russia till the German army occupied

Kharkov in March 1918 and some order was restored by the German soldiers.

However, after the German withdrawal in November, there was a complete social

breakdown. Food, electricity and heating oil was scarce. Bortkiewicz describes

how his piano students had to sit at the piano in furs and hats, with

frost-bitten fingers, continuously drinking tea to keep warm.

The Bolsheviks did not spare Bortkiewicz and plundered his family estate

at Artiomowka. In the summer of 1919 he moved on to Crimea with his wife,

where he lived in two furnished rooms in Sevastopol with a view of the harbor

of Yalta. He rented a piano and composed his haunting Nocturne Op. 24, No.

1, subtitled Diana, during a wonderful moonlit night.

He had decided to leave Russia and waited till November of 1920 till he found

place on a crowded steamer bound for Constantinople, now Istanbul, arriving

with only 20 dollars in his pocket. His 1.5 million roubles were totally

worthless! But his fame had preceded him and soon he was able to attract

a cosmopolitan group of students from the well-to-do families in the city.

He taught them in French and English.

"Knowing the strict morals of Orientals," he writes, "I had to put up with

the presence of mamas or aunts who did not want to leave me alone with young

ladies, and read a book during my lessons, while casting suspicious glances

at my hands; and even with the presence of a husband who suddenly appeared

in the room and looked at my posture jealously." Bortkiewicz did have a sense

of humor!

In almost two years he had earned enough money from piano lessons and concerts

to think of emigrating to Europe. He had established his old business contact

with his publisher D. Rahter and set his goal as Vienna. He did not regret

his decision to move on; within a couple of months after his departure,

Kemal-Pascha had taken over Istanbul and the Sultan had abdicated. The majority

of his students, Greeks and Armenians, had to leave the city.

A new chapter in his life began. He passed through Sofia to Belgrade where

he had to wait for quite some time till he obtained an Austrian visa. Finally,

he and his wife boarded a Danube steamer and arrived in Vienna on 22 July,

1922.

In 1928 he went to Paris for half a year and then to Berlin, a city which

he loved; but again he had to leave because, being a Russian, he was persecuted

by the Nazis and his name was deleted from all musical programs. He returned

to Vienna in 1935 where he found a suitable residence in Blechturmgasse.

He remained in this city till his death in 1952.

The war years 1939-1945 was a terrible time for Bortkiewicz and his wife.

Three times, as he recounts in his letters to van Dalen, he was close to

death as the Allied bombs rained down on Vienna and the Russians advanced

on the city. A postcard from December 1945 reveals how he lived. "I am writing

to you from my bathroom," he writes there, "where we have crept in, because

it is small and can be warmed now and then by a gas flame... I don't believe

in happiness anymore, rather that I am a dead man." To add to his woes, his

wife's mental condition had deteriorated due to the hardships of the war

and he had to look after her continuously.

All of his music scores were destroyed during the bombardment of Leipzig

and his financial situation was desperate. His friend van Dalen, too, seemed

to have deserted him in the post-war years, adding to his growing melancholia.

He had been suffering from a stomach ailment for quite some, most probably

cancer, and on the advice of his physician, he decided to undergo an operation

in October 1952. He never recovered and passed away on the 25th of October,

1952. His wife, who was childless, died 8 years later in 1960 in Vienna.

It seems Bortkiewicz was on the wrong side of the fence wherever he went.

Though he spoke German fluently and even wrote his "Erinnerungen" in this

language, he was not looked upon too kindly in Austria, perhaps because of

his Russian origin and the behavior of Soviet troops when they occupied Vienna.

In 1977, twenty five years after his death, the Viennese civic authorities

levelled his grave in the city cemetery.

The autographs of his unpublished works, which were in van Dalen's possession

were bequeathed by van Dalen to the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague. It took

me quite an effort to locate Bortkiewicz's Sonata No.2, Op. 60 in this museum

and publish it in 1996. Very recently, Malcolm Ballan of Southampton, England,

finally found the autographs of his 2 Symphonies in the Fisher Collection

in Philadelphia, where Bortkiewicz had sent them for safe keeping just before

his death.

It interesting to speculate why Bortkiewicz never recorded his own music,

though he lived into the age of high fidelity. Why, one can even hear Scriabin

or Saint-Saens playing their works, thanks to the reproducing piano. A clue

to his "old-fashioned" attitude is to be found in the remarks he makes in

the Erinnerungen. "It is certain, at least for me, that the Mechanization

of Art nowadays is a big backward step. The cinema is the greatest enemy

of theatre, the radio - of music at home and of concerts." I guess he stuck

to his beliefs and refused to record his music "mechanically" for posterity,

though during the war years he performed his works in various radio stations.

In 1995 I decided to record all of Bortkiewicz's music that I had in my

possession, including all orchestral works. So far I have made 11 CDs of

his music including the two great Symphonies, in the hope that the magnificent

music of this last great romantic will not be forgotten. © Bhagwan

N. Thadani

FURTHER READING

"Recollections, Letters and Documents" Translated from German

and annotated by B.N. Thadani. Cantext Publications, Winnipeg, Canada. 1997.

ISBN 0-921267-26-6

"Discovering the music of Sergei Bortkiewicz," Clavier, Jan.

1996.

List of works

I have always been passionately fond of the piano, having played it for more

than 50 years, and lately have taken to publishing rare piano scores and

recording the music on CD's. My interest is in the Russian composers of the

late 19th, early 20th centuries, specially the music of Sergei Bortkiewicz

(1877-1952) Felix Blumenfeld (1863-1931), Constantin Antipov (1859 - ?),

Cesar Cui (1835-1918), and the French composer, Benjamin Godard (1849-1895).

I discovered Bortkiewicz's Second Sonata #2, Op. 60 in a museum in the

Netherlands and published it in 1995. Since then I have published the following

music scores under the Cantext Publications imprint.

Sonata #2, Op. 60, Sergei Bortkiewicz, 1995 - $10

Selected Works, Bortkiewicz, 1996 - $10

Sonate-Fantaise, Blumenfeld, 1996 - $10

Selected Works, Blumenfeld, - $10

Russian Rhapsody, Bortkiewicz - $10 from an autograph discovered in a museum

in the Netherlands

Recollections, Letters and Documents" by Bortkiewicz, which I translated

from the German, and which, with my annotations, is the definitieve biography

of the composer,1997 - $15

Concerto #2, Op. 28, Bortkiewicz for the left hand, arranged for solo piano

by me. - $14

All prices are in US $ and include postage

My article on Sergei Bortkiewicz appeared in the Jan. 1996 number of the

music magazine Clavier. Please contact me if you are interested in

any of these publications.

Recordings

So far I have made 19 CDs of the works of my favorite composers listed below.

Most of these recordings are world premier recordings; in fact, it may be

the first time they have been played after almost 6 decades. A synthesizer

was used for the orchestral accompaniment for the concertos.

Each CD costs $17 US or the equivalent in local currency. You are entitled

to a 20 % discount if you order more than one CD, and can pay me by personal

cheque made out to me. Allow 10 days for delivery

CD-1 Felix Blumenfeld - Piano Works

Preludes, Op. 17 (1 to 24); Sonate-Fantaisie, Op. 46; Preludes, Op. 12

(1 to 4)

Deux Morceaux, Op. 37; Deux Fragments, Op. 33

CD-2 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works Vol. 1

Etudes, Op. 15 (1 to 10); Etudes, Op. 29 (1 to 12); Trois Morceaux Op.

6 (1 to 3)

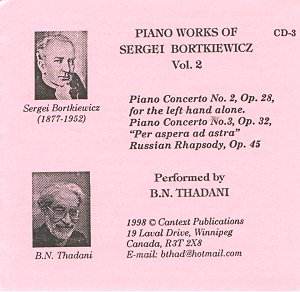

CD-3 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works, Vol. 2 Piano Concerto No.

2, Op. 28 for the left hand alone; Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 32 "Per aspera

ad astra"; Russian Rhapsody, Op. 46

CD-4 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Works, Vol. 3 "Othello", Op. 19;

Oesterreichische Suite, Op. 51; Trois morceaux pour violoncello et piano,

Op. 25; Trois morceaux, Op. 6

CD-5 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works Vol. 4 Sonata No. 2, Op.

60; Quatre Morceaux pour piano, Op. 3 Impressions. Sept Morceaux pour piano,

Op. 4; Minuit: Deux Morceaux, Op. 5

CD-6 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works, Vol. 5 Ein Roman für

Klavier, Op. 35; Deux morceaux, Op. 7; Esquisses de Crimée, Op. 8;

Six Preludes, Op. 13; Trois Morceaux, Op. 24

CD-7 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Works, Vol. 6 Cello Concerto, Op. 20;

Trois morceaux pour piano, Op. 12; Trois morceaux, Op. 24; Im 3/4 Takt, Op.

48

CD-8 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Works, Vol. 7 Violin Concerto, Op. 22;

Sonate pour violon et piano, Op. 26; Marionettes, Op. 54

CD-9 Felix Blumenfeld - Works, Vol. 2 Deux Nocturnes, Op. 6; Valse

Impromptu, Op. 16; Nocturne Fantaisie, Op. 20 Trois Morceaux, Op. 21; Impromptu,

Op. 26; Dix Moments Lyriques, Op. 27 Près de l'eau, Op. 38; Deux

Impromptus, Op. 45; Allegro de concert pour piano et orchestre, Op. 7

CD-10 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works, Vol. 8 Sonata No. 1, Op.

9; Lamentations et Consolations, Op. 17; Pensées Lyriques, Op. 11

CD-11 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works, Vol. 9 Elégie, Op.

46; Dix Preludes, Op. 33; Sieben Preluden für Klavier, Op. 40; Trois

Valses, Op. 27; Lyrica Nova, Op. 59; Der kleine Wanderer, Op. 21

CD-12 Sergei Bortkiewicz - Piano Works, Vol. 10 Tausend und eine

Nacht, Op. 37; Aus meiner Kindheit, Op. 14; Ballade, Op. 42

CD-13 C. Antipov and C. Cui - Piano Works Antipov: 5 Morceaux,

Op. 5; Preludes, Op. 8, 10; Miniatures, Op. 9 Valse et Etude, Op. 11; Nocturne,

Op. 12 Cui: Trois Valses, Op. 31; Cinq Morceaux, Op. 52; Esquisse;

Intermezzo; Impromptu; Scherzino

CD-14 Felix Blumenfeld - Piano Works, Vol. 3 Quatre Morceaux, Op.

2; Deux Morceaux, Op. 22; Suite Lyrique, Op. 32; Ballade, Op. 34; Cloches

- Suite, Op. 40; 2 Fragments Lyriques, Op. 47; Trois Nocturnes, Op. 51; Episodes

de la vie d'une danseuse, Op. 52 Vier Klavierstücke, Op. 53

CD-15 Benjamin Godard - Piano Works Sonate Fantastique, Op. 63;

Deuxième Sonate, Op. 94; Chemin faisant, Op. 53 (1, 6); Au matin,

Op. 83; Etude, Op. 149-II, No. 4 Etude, Op. 149-IV, No. 1; Fourth Barcarolle;

Valse chromatique, Op. 88 Chopin, Op. 66, No. 2

CD-16 C. Antipov and C. Cui - Works, Vol. 2 Antipov: Trois

Etudes pour piano, Op. 1; Variations, Op. 3; Quatre Morceaux, Op. 6; Allegro

symphonique pour orchestre, Op. 7; Impromptu et Valse, Op. 13

Cui: Trois mouvements de Valse, Op. 41; Vier Klavierstücke,

Op. 22; Tenèbres et Lueurs

CD-17 Benjamin Godard - Works, Vol. 2 Etudes Artistiques (1 to

12), Op. 42; Musset; Kermesse, Op. 51; Renouveau, Op. 82; Tziganka, Op. 134;

Fantaisie Persane for piano and orchestra, Op. 152.

CD-18 Benjamin Godard - Works, Vol. 3 Etudes artistiques (13 to

24), Op. 107; Barcarolle, Op. 77; Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 148; Barcarolle,

Op. 105

CD-19 Benjamin Godard - Works, Vol. 4 Impressions de Campagne (1

to 16), Op. 123; Lanterne Magique, Op. 55 (1, 3, 6); Les Hirondelles, Op.

14; Introduction et Allegro pour Piano et Orchestre, Op. 49

Available from:

Bhagwan Thadani

19 Laval Drive

WINNIPEG

CANADA R3T 2X8

bthad@hotmail.com

REVIEWS

Sergei Eduardovich BORTKIEWICZ

(1877-1952) Vol. 2: Three works for piano and

orchestra

Piano Concerto No. 2 (1922) 25 mins

Piano Concerto No. 3 Per Aspera ad Astra (1927) 28 mins

Russian Rhapsody (1930) 13 mins

Bhagwan Thadani

(piano) 'orchestra directed' by Daniel Oke Bhagwan Thadani

(piano) 'orchestra directed' by Daniel Oke

Note: the

orchestral sound is produced using computer generation to synthesise the

orchestral canvas. BHAGWAN THADANI private recording CD3 [66.38] Note: the

orchestral sound is produced using computer generation to synthesise the

orchestral canvas. BHAGWAN THADANI private recording CD3 [66.38] |

Bhagwan Thadani (a pianist now living in Winnipeg, Canada) has made the tracing,

performance and recording of the works of Bortkiewicz a life's mission. His

achievement is staggering, prompting comparisons with the LP/cassette era

legacy of Grant Johanessen's complete Liszt and Busoni cycles. Years have

been spent in tracing, reprinting, performing and recording the works. There

are currently ten volumes of CDs published by Mr Thadani and another ten

or so recording the neglected piano works of Antipov, Blumenfeld and Godard.

This achievement seems to have been studiously ignored by the usual review

channels perhaps because Mr Thadani has had to use a computer synthetic to

record the sound of the orchestral part of the concertos.

This present disc acts as a nice complement to the Hyperion CD of the First

Piano Concerto with two single movement concertos each playing five or minutes

under half an hour and prompting comparisons and contrasts with the Medtner

Ballade Piano Concerto (No. 3). The second concerto and the rhapsody

were both written for the left hand alone and, unsurprisingly, were commissioned

by Paul Wittgenstein, the dedicatee of the more famous Ravel, Schmidt, Strauss

and Korngold concertante works for piano left-hand.

Second Piano Concerto

This launches in an atmosphere of vehement hyper-romantic turbulence sustained

for most of its compact length. It is more a child of tempest than anything

in Rachmaninov and the soloist's part follows a similar style. Along the

way there are Tchaikovskian episodes and the big theme has more than a little

in sympathy with Rachmaninov's piano concerto No. 2. This work however seems

more modern than the Tchaikovsky. It has more in common with Rachmaninov

and Medtner. The big theme from the latter's second piano concerto is also

hinted at. It has more gravity than the Saint-Saens concertos or the Palmgrens,

enjoyable though they are. It has the bounce and élan of the more

exuberant moments from the Delius piano concerto. The orchestral impression

is one of urgency and no little excitement. A carefree tone and humming bright

eagerness reaches out to us in the closing pages of the first movement suggesting

momentary inspiration from Borodin's Polovtsian Dances. The themes

and treatment are more openly accessible than the ochre-toned subtlety of

the Medtner concertos. If you appreciate the Tchaikovsky second piano concerto,

the Rachmaninovs, the Arensky and the Scriabin concertos you will like this

... and like it very much. This is a comprehensively enjoyable romantic concerto

which stands out from amongst the crowd.

The synthesised accompaniment will not fool you into thinking this is a real

orchestra but that was not the intention. What you get is a mind's ear

approximation of the orchestral sound and for the most part the ear

psychologically 'reconstructs' an orchestral sound quite successfully 'on

the fly'. The violin and percussion instrument sounds are not successful

although they are less of a problem in orchestral numbers than in solo. The

cello solo in the cello concerto is very believable as also is the horn solo

towards 19.40 in the first movement of the second concerto. At all times

an indulgent and kindly ear is necessary but then why make obstacles for

yourself. Until orchestras and record companies take up these works we can

enjoy Mr Thadani's precious CDs as pathfinders.

As for the solo part Mr Thadani probably knows these concertos better than

any man alive. Bonfires of notes, clouds of sparks, sheet lightning and

thunderous display are all there in abundance. His technique seems fully

equal to the challenges both in bravura and in reflection.

Third Piano Concerto

While the second concerto is hardly ever out of wind-blown flight and romantic

torment the third occupies a subtle and more varied landscape although delivering

far from short measure in the late-romantic upheaval stakes. The soloist

nicely catches the variations in tempo and the orchestra (as with

the second concerto) is comfortably integrated with the solo piano picture.

The exertion and intensity is grand in scale and well worth your time. Listen

to the nicely conjured horns at 10.25 accompanying the piano. Once again

there is an infusion of Rachmaninov's grand and faintly lachrymose heroism;

at all times dignified and grandly clangorous like a landscape of noisy bell

towers in icily sonorous counterpoint. Little details stand out: e.g. the

harp, totally believable, at 15.50 and 18.21 in partnership with the solo

piano. A stunning change of gear and a great relaxation comes at 16.30 where

pulse slows. The work is never boring and always mobile with crystalline

incident at times evocative of the Grieg concerto. The peroration from 26.17

is grandly leonine and frankly totally enjoyable. Not once does display,

of which there is a lot, suffocate musical ideas. Display and poetry, fireworks

and dramatic moment are in equipoise.

Russian Rhapsody for Left Hand alone

This starts with galloping theme in a nocturnal journey. In sympathy with

the other two concertos this has a franker melodic debt to Russian folk song

(yes - The Volga Boat Song! - 09.02) and the Kuchka's brand of nationalism.

This drifts Bortkiewicz into the mildly corny in the manner of Chopin's

Krakowiak during the central dance episode. Good fun nonetheless.

Now I do hope that Mr Thadani will look at one of Rachmaninov's British

exponents: Richard Sacheverell Coke whose six piano concertos and extensive

piano solo catalogue made a brief éclat in the UK during the

1920 and 1930s and was then utterly forgotten.

Of the three discs I have heard so far this is the one to get if you must

limit yourself to one purchase.

Reviewer

Rob Barnett

(special category computer synthesised orchestral and solo cello sound)

Each CD costs $17 US or the equivalent in local currency. You are entitled

to a 20 % discount if you order more than one CD, and can pay me by personal

cheque made out to me. Allow 10 days for delivery

As early as Vol. 2 of his momentous Bortkiewicz series Bhagwan Thadani decided

to include works with orchestra. It would cost far too much to hire a real

orchestra so he opted for a synthesiser to give an approximation of the

orchestral partner. While the piano concertos present a real sound (Mr Thadani's

piano) alongside the synthesis the violin concerto is totally synthetic in

this recording with both solo and orchestra emulated by the synthesiser.

The light-stepping long-limbed theme of the first movement rolls out with

tireless stamina - a tribute to the composer's fertility of invention. However

enjoyment requires far more suspension of disbelief or psycho-acoustic

re-creation than the disc of the two piano concertos. The obstacle is that

the sound of the violin solo must be a less successful approximation than

the results achieved for the cello. It sometimes comes perilously close to

sounding like a Dutch theatre organ - miniaturised. The keyboard origins

of the synthesis are difficult to mask and the undulating legato of the bowed

instrument can be difficult to emulate. You can see where it is going and

how the violin would sound but a greater leap of faith is required.

Putting this aside, athletic lyricism is there in full but the temperature

is far less than the super-heated romantic furnace of the piano concertos.

The ambition is linked to the same horizons as the Saint-Saens violin concertos

rather than say the Elgar or the Tchaikovsky or the Brahms. The

central Poème is stronger in drama with touches of Tchaikovsky's

Pathétique final movement. The final movement has an infusion of

squeeze-box jollity, Rimskian Easter festivals and the air of the Glazunov

violin concerto. The work is naively engaging, somewhat conventional and

not as impressive as the taut and high pressure piano concertos or cello

concerto. Still it is fully worthy to take its place in Hyperion's romantic

violin concerto series with the Arensky, de Boeck, Pfitzner, Reger, Freitas

Branco, the splendid Mieczyslaw Karlowicz and from a later era but still

consummately on-song the Janis Ivanovs concerto.

The Sonata takes us back to the natural sound of Mr Thadani's piano but leaves

exposed the challengingly Hammond-accented sound of the solo violin. The

relaxation and diversion of the concerto is here contrasted with a much more

grown up and Tchaikovskian passion. This might very easily arrange as a violin

concerto. The main theme of the first movement is insistently shadowy and

impassioned. Thankfully the piano part is not at all the subjugated and purely

accompanimental 'along for the ride' role we might have feared. The middle

andante is charmingly done and clearly a movement of some gentle melodic

confidence. A darting allegro vivace rounds out the sonata in humming

bird brio and flouncing dervish fantasy. Do I detect a touch of the Istanbul

where the composer spent the years 1919-1922. By the way the violin sound

is much more successful in the more percussive staccato moments.

The Marionettes is a sequence of nine skilful salon charmers - pert little

character pieces designed for the piano stool commercial market and with

titles such as The Cossack, The Gipsy and Teddy Bear.

These are nicely despatched by Mr Thadani being more abrasively interesting

and emotionally developed than a Macdowell sequence. The Chinese and

Teddy Bear are more challenging, stylistically speaking, with the

former linking into the enthusiasm for 1920s (and earlier) chinoiseries e.g.

the Bethge translations of Li Tai Po for Mahler's Das Lied and the

Chinese songs of Schierbeck, Bliss, Lambert and Van Dieren.

Reviewer

Rob Barnett

(special category computer synthesised orchestral and solo cello sound)

Brahms first symphony is sometimes spoken of as Beethoven's tenth. Well,

Bortkiewicz's cello concerto plays like the Cello Concerto Tchaikovsky (or

for that matter Rachmaninov) never wrote. It is in two movements, the first

of which is torrentially melodic with suggestions of the last movement of

Tchaikovsky's Pathétique and of Rachmaninov and towards its

end a Mozartian airiness carried by the dialogue of flute and cello (15.12).

The surging and receding passion takes us once again into the world of

Rachmaninov's second piano concerto.

The second movement buzzes and hums with a melting pot of rumba, tarantella

and havanaise. Although of greater emotional breadth it reminded me of Glazunov's

and Frank Bridge's brief character pieces for cello and orchestra but the

lights and darks are deeper. This is an exciting and dashing romantic concerto

which should immediately be taken up by the world's inspirational young cellists

otherwise trapped in a repertory limited by the standard concert 'draws'

of Elgar, Dvorak and Saint-Saens.

The whole listening experience is greatly aided by the fact that the cello

sound is a more credible synthesis than the sound of the solo in the violin

concerto. Listen for example to the section of cello sound at 2.16 in the

first movement.

The rest of the disc takes us back to the natural sound of Mr Thadani's piano

and his dedicated pianism.

The 1910 trilogy of three dances (Morceaux) floats past us in procession:

a dignified Mazurka, a Gavotte of sparkling velocity and a

stormy Polonaise somewhat predictive of the tumult of the second and

third piano concertos.

The trio of piano pieces from twelve years later starts strongly with the

Nocturne-Diana, inspired by a wonderful moonlit night in Yalta in

which the shades of Chopin and Rachmaninov drifted in nostalgic ease. The

Valse Grotesque (Satyre) is of quasi-Bartókian

percussiveness which carries over into the final panel (Eros) and

from which emerges music paralleling by Rachmaninov's Preludes.

The waltz sequence of six miniatures are light on the listener and so

undemandingly entertaining that they can be overheard. The final allegro

robusto is memorably tense.

I can hardly wait to hear Bortkiewicz 's two symphonies. Going by Grove V

they should date from circa 1935 and 1939 respectively. After many years

these were finally tracked down in the Philadelphia Free Library. Mr Thadani

is now busy producing a recording of these symphonies using the now accustomed

computer synthesis. We can hope that these and other works will be taken

up by adventurous recording companies and orchestras. Perhaps someone will

now start to take up this same approach to other composers including Josef

Holbrooke and Frederic Cliffe. Perhaps Mr Thadani will also turn his attention

to the Op. 53 Overture and the Yugoslav Suite both circa 1938.

As usual, succinctly informative notes are provided by Mr Thadani on 'plain

jane' paper inserts - nicely designed.

Reviewer

Rob Barnett

(special category computer synthesised orchestral and solo cello sound)

Each CD costs $17 US or the equivalent in local currency. You are entitled

to a 20 % discount if you order more than one CD, and can pay me by personal

cheque made out to me. Allow 10 days for delivery

Bhagwan Thadani

19 Laval Drive

WINNIPEG

CANADA R3T 2X8

bthad@hotmail.com

MR THADANI's website is at

http://www.geocities.com/bthad.geo or

http://www.geocities.com/Vienna/Strasse/7136/