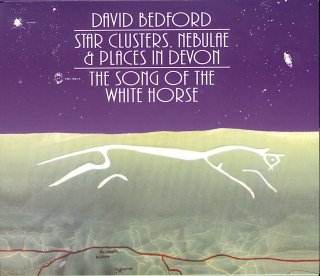

David BEDFORD

Song of the White Horse also featuring Star Clusters,

Nebulae & Places in Devon

Nash Ensemble & Queens

College Choir conducted by Steuart Bedford, with Mike Ratledge and David

Bedford, keyboards, soloist Diana Coulson (Song of the White Horse) / Chorus

and Brass of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Star Clusters…) * produced

and engineered by Mike Oldfield

Nash Ensemble & Queens

College Choir conducted by Steuart Bedford, with Mike Ratledge and David

Bedford, keyboards, soloist Diana Coulson (Song of the White Horse) / Chorus

and Brass of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Star Clusters…) * produced

and engineered by Mike Oldfield

Classicprint CPVP011CD

* [48:52]

Classicprint CPVP011CD

* [48:52]

Purchase direct

http://www.voiceprint.co.uk/index.htm

David Bedford is a composer with a foot in at least two camps. Born in 1937,

he studied at the Royal College of Music under Lennox Berkeley, in Venice

with Luigi Nono and at the RAI Electronic Music Studio in Milan. A contemporary

composer with the reputation to have Radio 3 devote a whole 105 minute programme

of late night broadcasting to his works in 1998, he is also a musician whose

collaborations with Tubular Bells rock-composer Mike Oldfield span

three decades, and who seems to be comfortable on that edge where progressive

rock has ambitions to orchestral seriousness. In conjunction with Kevin Ayers

of Soft Machine Bedford combined rock with acoustic music (their band

was Whole World).

Star's End was perhaps the most acclaimed piece to come out of this

period, and is just one of several to reveal Bedford's interest in the celestial

lights: other works include A Dream of the Seven Lost Stars (1964-5)

, Music for Albion Moonlight (1965), The Tentacles of the Dark

Nebula (1969), The Sword of Orion (1970) Some Stars Above Magnitude

2.9 (1971), Twelve Hours of Sunset (1974), Ocean Star a Dreaming

Song (1981), Of Stars, Dreams and Cymbals (1982), An Island

in the Moon (1985-6). Given that Mike Oldfield has released a concept

album based upon Arthur C. Clarke's Songs of Distant Earth, it is

perhaps no surprise to discover that Bedford is currently at work on an oratorio

based upon the same novel. Which brings us to this current disc, produced

and engineered by Mike Oldfield, and Star Clusters, Nebulae & Places

in Devon for mixed chorus and brass (1971).

The choir is divided in two. Choir one sings a text comprised of nothing

but the names of star clusters and nebulae. Choir two, a text which is simply

a list of place names in Devon (and progressive rock fans might like to note

that one of them is Yes Tor, the feature which helped inspire the name of

the 1978 album by the band Yes.) The only point of connection seems to be

that there are many Bronze age remains in Devon, such that (the anonymous

programme note, presumably written by the composer, explains), "When the

hut-circles of the Bronze Age people were in daily use, roughly three and

a half thousand years ago, the Globular Star Cluster in Hercules shone out

as they slept." To which I have to add, "so what!" The writer further tells

us, "When we look at it though a telescope, we are seeing exactly the

same light as shone out over the Bronze Age people, for the cluster is

some three and a half thousand light-years away and that is when the light

started on its long journey to us." (my italics). Of course, the light that

shone out over the Bronze Age people is not exactly the same light we see

three and a half thousand years later. The light the Bronze Age people saw

began its journey seven thousand years ago…

The whole concept strikes me as pretentious and pointless, and I am afraid

the music impresses me little more than the idea behind it. It seems typical

of late 60's experimental music, the concept given more value than the ears

of the unfortunate listener. The actual names in the text are so fragmented

into sung chords as to be unrecognisable, the result being a dissonant choral

sound almost certainly inspired by a viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey

(1968) and the music therein by Ligeti, while the agitated brass at times

seems as if it may even have had an influence upon John Williams in his writing

for Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). The range of bizarre

vocal textures Bedford achieves is certainly accomplished, but in the end

it all sounds rather too much like the music from some very dark and unsettling

horror film, and I would happily never hear it again. The recording is vivid,

but there is some occasional peak distortion on the left channel which is

not really acceptable in a 1999 studio production.

The Song of the White Horse (1978) is in five sections but plays in

one continuous track running 24 minutes. Written for an edition of the BBC

series Omnibus, it is a musical evocation of the Ridgeway footpath

between Wayland's Smithy (beyond the Bronze Age to a Stone Age burial chamber)

and the old chalk hill feature, the White Horse of Uffington. Opening with

lugubrious electronic keyboards, soon joined by static woodwind, the atmosphere

evoked is not so distant from Bernard Herrmann's Journey to the Centre

of the Earth (1959) film score. After this beginning, much use is made

of delay effects, particularly on the trombones, combined with a comical

ship's siren effect which proves to be the composer blowing into The Blowing

Stone at the bottom of White Horse Hill. Then at 9:27 the song itself begins,

first with a solo vocal, soon joined by an uncannily detached and tranquil

children's choir. The words, taken from The Ballad of the White Horse

by G.K. Chesterton certainly offer more substance than those of Star

Clusters… In-fact, there are an awful lot of word to get though

in this epic tale of 'the days of (King) Alfred'. Unfortunately the music

is insufficient to maintain the interest as the choir wades its way steadily

forward, while some of the synthesiser lines seem terribly dated. This central

section lasts over ten minutes and does nothing but accelerate, becoming

increasingly frenzied with the addition of more instruments. Ravel's

Bolero, it is not. The Postlude, sung like the opening, by Diana Coulson,

has an otherworldly appeal, but is insufficient to justify what has come

before. At half the length this might be quite an interesting piece, but

stretched so far it is simply too much of not enough.

Reviewer

Gary S. Dalkin