| Len Mullenger

CD booklet With Permission Hyperion Records

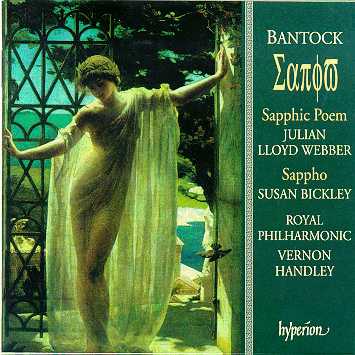

Sappho

(Prelude and Nine Fragments for Mezzo-Soprano and

Orchestra)

|

Sapphic Poem

Susan Bickley - mezzo soprano

Julian Lloyd Webber - cello

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Vernon Handley

Hyperion CDA66899 |

|

When I heard the Hyperion recording of Sappho I was "Knocked Sideways", to

use the words of the young Benjamin Britten on his first hearing of Frank

Bridge's "Enter Spring". When the record reviewers get round to this disc

they will be reaching for the superlatives and it would not surprise me if

it were to end up as Gramophone's Record of the Year. Sappho is a sensual

and voluptuous orchestral song cycle for mezzo voice that has been virtually

hidden for 90 years. Bantock creates a warm-textured thickly upholstered

sound that has been caught to perfection by the engineer (Tony Faulkner)

with a perfect balance between a large orchestra and the soloist, the mezzo,

Susan Bickley. Following an orchestral prelude, there are nine songs and

the work lasts fully an hour.

Sappho was written whilst Bantock was Principal of the Midland Institute

School of Music in Birmingham, just before he was appointed Peyton Professor

of Music at the University of Birmingham. Bantock had met his wife, Helena

von Schweitzer, in 1896 and had married in 1898 (apparently the von was an

affectation and she soon also shortened her name to Helen). She was a poetess

and subsequently wrote the texts for many of Bantock's works. The Sappho

songs are based on poems written by the Greek poetess, Sappho, who lived

on the Island of Lesbos in the middle of the 7th Century. Her poetry was

said to be inspired, passionate and also erotic. Very little has survived.

It had been collected into nine volumes and deposited in the great Library

of Alexandria. This was all lost when Alexandria was sacked in the fall of

the Alexandrian empire at the end of that century. Other copies survived,

possibly for another century, but they too were eventually destroyed, probably

because of the lesbian connotations which would have been anathema to the

early Christians. What has survived has been mainly due to her work having

been quoted in part by other poets and scholars - often only a single line.

These still turn up with one having been discovered on a strip of papyrus

used to wrap a mummified crocodile.

Surviving fragments were collated and translated by Henry Wharton in 1885

and it was from this that Helen Bantock worked. One poem, "Ode to

Aphrodite", survived intact and this is the first poem in the Bantock

cycle. There also existed a considerable extract of a second poem which is

used in Bantock's sixth song: "Peer of Gods he seems". The remainder

were fragments of a line or two which Helen Bantock arranged in a seemingly

logical assembly although the original Sapphic relationships cannot be known.

Occasionally Helen seems to have composed some lines herself where she felt

them to be needed. Altogether she utilized about 50% of the Wharton collection.

The songs appear to have originally been composed for the contralto voice

(1906) but were soon adapted for mezzo for the orchestral score of 1909.

There were possibly only a couple of complete performances before the scores

were lost in the War. They were reconstructed for the concert celebrating

the 50th Anniversary of his death held in Birmingham in November 1986 by

the University of Birmingham Orchestra conducted by Professor Stephen Banfield

with Sarah Walker as soloist. Using these same parts, Hyperion went on to

record the work with Susan Bickley and Vernon Handley conducting the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra

Sappho opens with a. 10 minute orchestral prelude. This was possibly written

after the songs as, to quote Stephen Banfield, "Bantock sticks all the best

bits together", but it was the first to be orchestrated. The prelude opens

with the harp which has a very prominent part in this cycle evoking the playing

of Sappho who played both harp and lute. Melodies from various songs are

woven together although not in the order in which the songs subsequently

appear. The prelude has frequently been played on its own in concert performance.

The songs follow as below:

1. Ode to Aphrodite 7'16

This is the only complete poem to have survived. Sappho has been spurned

by her lover and appeals to Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus and Goddess of Love.

This is clearly not a unique plea: "Now hither come,

as once before thou camest."

2. I loved thee once, Athis, long ago 6'33

This song is instantly memorable for its intensity. We hear Sappho's harp

against a cor-anglais of haunting longing. Sappho is both resigned and scornful

of a former love who has left her for another. She will be forgotten whereas

Sappho will live on because she has gathered "the roses of Pieria". Lewis

Foreman explains in the notes accompanying the recording that Sappho is referring

to her poems. "Pieria was in fact part of Macedonia, North of Mount Olympus,

the home of the Muses. The roses of Pieria are simply poems."

3. Evening Song 2'17

This, the shortest of the songs, is a beautiful nocturne with string

accompaniment (and triangle; Stephen Banfield declares Sappho to have the

biggest triangle part in the world). Sappho greets the evening that will

reconcile all that has been scattered by the day. In the second part of the

poem she greets the coming of Spring.

4. Stand face to face, friend 8'06

The first two verses are set to swirling strings and then the first paean

to love with harp and triangle accompaniment:

|

So all night long,

when sleep holds the eyes of the weary,

Before the feet of Love

May I set my tireless singing.

Ah delicate love,

More precious than gold,

Sweeter than honey,

softer than the rose-leaves,

Beautiful Love!

|

Gradually the full orchestra sweeps in building to a passionate climax with

|

Let us drain a thousand cups of love |

and then pulling back for

|

O my sweet, O my tender one. |

It is the floating of the vocal line over the orchestra that reminds me so

strongly of similar settings by Chausson (Poeme de l'amour et de la mer

of 1892) or even of some of the late Strauss songs. The movement's end is

underpinned by three beautifully caught strokes on the bass drum and gong

and this is echoed in:

5. The moon has set 5'52

This is the desolate centre of the work which Banfield describes as a Mahlerian

funeral march which I find also has a lot in common with On the Lagoons from

Berlioz's Nuits d'étè; and again with Chausson. It is

midnight and Sappho is asleep but alone. To rising consternation in the orchestra

she realises she may always remain alone. She mourns:

|

Alas! I shall ever be maiden

Neither honey nor bee for me. |

6. Peer of the Gods he seems 4'13

There is still an all-pervading sense of loss here as Sappho sees the one

that she loves and has lost (Dare I to love thee?) now with a man. She feels

as one who is dead:

|

Sight have I none, nor hearing,

cold dew bathes me,

Paler than grass I am, and in my madness seem as one dead,... |

7. In a dream, I spake 4'23

In her dream Aphrodite tells Sappho that is to be considered evil to die

(by suicide; Sappho is believed to have ended her own life) - if it were

not so the gods would do it. When Adonis, who was the beloved of Aphrodite,

was killed by a wild boar, Aphrodite's grief was so great that Zeus allowed

Adonis to alternate six months with the living and six months among the dead.

This is correlated with the six months from Spring to Harvest and the six

months when the world appears dead.

8. Bridal Song 4'40

The mood brightens for the last two songs. With chirruping wood-wind and

tinkling triangle Bantock celebrates the institution of marriage. Sappho

loses her lover to a man; is this the only way Sappho can prevent having

empty nights by herself?

|

Happy bridegroom, now is thy wedding come

And thou hast the maiden of thy heart's desire |

9. Muse of the golden throne 5'28

With the accompaniment of Sappho's harp we have a final hymn to the Cyprian

goddess; Aphrodite, goddess of love.

|

Come, Cyprian Goddess, and in cups of gold

Pour forth they nectar of delight,

Thou and thy servant, Love! |

The work ends in neither celebration nor resignation. All emotions have been

visited during this cycle and Sappho has finally found peace and contentment.

As if this were not riches enough the disc also contains a performance of

Sapphic poem for cello and orchestra which is contemporaneous with Sappho,

receiving its first public performance in 1906 and published with orchestral

accompaniment in 1909. The cellist is Julian Lloyd Webber, continuing his

championing of British music. The piece has a delicate beauty but without

quite engaging the range of emotions found in Sappho.

References:

Booklet notes by Lewis Forman accompanying Hyperion CDA66899

The Bantock Society Journal Volume 2 No.1 Summer 1997 containing a

number of articles on Sappho:

Bantock and Birmingham by Stephen Banfield

Programme Notes, 50th Anniversary Concert by Stephen Banfield

Interview with Stephen Banfield by Rob Barnett

A Brief Comment on the Performance of Sappho by Sarah Walker

A Review of 1996 Sappho Performance by Lewis Foreman

Programme Notes, Reid Orchestral Concert 1921 by Francis Tovey

A Short Sappho Anthology

Since February 2000 you have been visitor number

Return to Bantock Main Page

Return

to Classical Music on the Web Return

to Classical Music on the Web |