Other Links

Editorial Board

-

Editor - Bill Kenny

Assistant Webmaster - Stan Metzger - Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN AND HEARD OPERA REVIEW

Sferisterio Opera Festival Macerata (3) ‘To the Greater Glory of God’ Verdi, I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata: Soloists, Conductor, Daniele Callegari; Director and Designer of Sets and Costumes, Pier Luigi Pizzi; Chorus Master, David Crescenzi; Choreographer, Gheorghe Iancu; Mime movement, Roberto Maria Pizzuto; Lighting Designer, Sergio Rossi. Sferisterio Macerata 1. 8.2010 (JB)

Cast: Arvino, Alessandro Liberatore; Pagano, Michele Pertusi; Giselda, Dimitra Theodossiou; Acciano, Luca Dall’Amico; Oronte, Francesco Meli

Production Picture © Foto Tabocchini

All these elements are to be found in the episodes surrounding the Crusades. Here too, unbridled sincerity was at war with reasoning and alternative vision. All the nuances of making realpolitik out of this have been superbly explored by Steven Runciman in the three definitive volumes which he left us. I have a nagging feeling that Condoleezza Rice and Dick Cheney are not familiar with Sir Steven’s excellent prose. Otherwise how could the same fatal mistakes go on being made?

Enter Giuseppe Verdi. He was a fervent nationalist and (at best) a lukewarm Christian. Still, he recognised the theme of unbridled sincerity versus alternative vision as fine operatic material. For good measure I Lombardi has a Romeo and Juliet sub-plot thrown in, whereby the virgin Christian, Giselda, is in love (secretly, of course!) with the Infidel, Oronte.

Verdi’s reputation was made with Nabucco, whose chorus va pensiero narrowly missed becoming Italy’s national anthem, so narrowly that I have met Italians who believe that it is the anthem and have no idea that it comes from Nabucco. That was at La Scala in 1842 and with the rallying cry for nationalism still rampant, Solera (librettist) and Verdi followed it up with another opera, the following year, still on the theme of a country unified against a common enemy, I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata. The pilgrims’ chorus O Signore del tetto ( Dear Lord in Heaven) in the last act of I Lombardi, for a while, rivalled va pensiero as first place for a national anthem.

I Lombardi is not quite the chorus opera that Nabucco is, but for all that, the “People” still form a key part of the drama. Herein a problem for Macerata: their chorus is not their strong point. Even in the famed chorus, while they managed to produce the right hushed dynamic, the attacks were a little rough. Daniele Callegari, who had been the finest of conductors in La Forza del Destino seemed, at various moments, to have some trouble holding stage and orchestra together. It sounded suspiciously under-rehearsed.

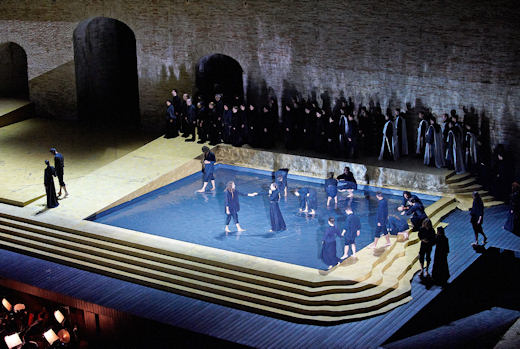

Still, what the chorus lacked in sound they almost made up for in the musicality of their movement, aided at appropriate moments by talented dancers and mimes. Pier Luigi Pizzi (Pigi) is rightly famed for his handling of crowd scenes and here again he was never so much as a second out in timing the smallest movement. He had clearly drilled them in the art of stillness (the hardest thing for an Italian chorus to do) so they appeared profoundly to understand the music. There were moments when I wished I was watching this with the rough sound switched off.

A group of mimes carry a huge crucifix round the endlessly long stage, launching it at various appropriate points and giving a real feel to the sense of pilgrimage. Some of the battle scenes came out as unintentionally comic. This is still the early, rum-tum-tum, village band Verdi ,and even Pigi’s genius couldn’t disguise the banality. There are moments when Verdi’s presumed banality sparks his best, but they are not in these scenes.

Pigi is irresistibly drawn to water. I recall a Tancredi at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro’s sports stadium where real boats arrived on real water. How is it when you can’t quite believe something you are seeing, it always makes a special impact? Here in Macerata, the pilgrims savoured the waters of the Jordan with their feet. With appropriate Pigi dignity, of course.

The soloist in what is effectively a violin concerto in the last act –Michelangelo Mazza- played with romantic commitment, and on stage too, following round the gifted ballerina, Anbeta Toromani, to whom the choreographer, Ghirorghe Iancu, had handed some rather clichéd steps.

The role of Giselda calls for a big, firm-voiced soprano, familiar from early Verdi operas, ideally suited to the young Ghena Dimitrova or Gwyneth Jones. Dimitra Theodossiou’s voice is certainly big. It is also anything but firm. Her idea of intonation (if idea it is –she seems oblivious to it) is on par with Florence Foster Jenkins. There was hardly a note which was in tune. She was also rhythmically insecure in places.Still, she blasted her way through the evening, earning applause from some evident fans. She pushes the notes from underneath, never quite managing to arrive at the intended pitch, if indeed there is an intention. A shapeless shambles.

Pagano is one of Verdi’s most challenging bass roles and one of the earliest in which Verdi conveyed character through a vocal line. Sadly, these subtleties seemed to escape Michele Pertusi, through he fared better in the final trio in which the villain becomes contrite.

Alessandro Liberatore rose to little more than all right in the challenging tenor role of Arvino. I would have thought that the admirable conductor, Daniele Callegari, would have got much more out of him, but it was not to be. Francesco Meli fared better as Oronte and cut a dashing figure in the third act.

In the end, it seems that a little more dedication to sincerity would have balanced some of the off-beat alternative vision. Non of the singers sounded sufficiently involved in their roles. Zeal has its uses too. It doesn’t always have to be of the fundamentalist strain.

Jack Buckley