Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL RECITAL REVIEW

From Bach to Debussy - Piano Recital by

George Hadjinikos:

Horto / Pelion, Greece, 17.8.2008 (BM)

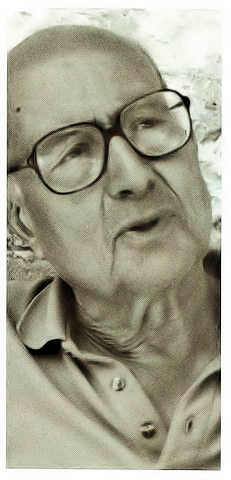

George Hadjinikos

Having devoted much of his life to music education (mainly in the

UK, but his summer master classes in his native Horto have also

become a tradition), it is no wonder that this evening, too, was

conceived as a lesson, entitled “A Living Journey Through the

History of Music from Bach to Debussy” and including brief

introductions to the pieces he was about to play. And he embarked on

this journey with an enduring Furtwängler quotation: “The issue

today is no longer what makes for good or bad music, but rather

music per se, what we mean when we use the term music.”

(Es

geht heute nicht mehr um gute oder schlechte Musik, sondern um Musik

schlechthin.)

Choosing Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in C major (from the 2nd

book of the Well-Tempered Clavier) as a point of departure – and

remarking in passing that the Fugue was of more academic than

humanistic value, he moved on to the ones in F sharp major and F

sharp minor in the 1st book, observing that the former

was a celebration of nature - his translucent playing, serving as a

celebration of the fugue as an art form, so much more than just

recurrently bringing out the theme - and the latter a reflection on

the plight of mankind – or words to that effect. At 85, Hadjinikos’

voice is somewhat reduced, which made it difficult to catch

everything he was saying, but it soon became evident that this was

not all that important: he was saying everything he needed to when

he sat down to play.

Next, after reminding us of how “Papa”

Haydn succeeded in infusing seemingly simple forms with so much

ingenuity that “nothing new came after him”, and referring to

Mozart’s genius and how he changed the world of melody, he chose

several movements from two of their lesser-performed sonatas – the

Allegro from Haydn’s Sonata in E flat major HobXVI: 28 and the

Adagio and Menuet I & II from Mozart’s K282 in the same key.

Particularly the Haydn was performed with such affection for every

single note that I couldn’t help but be reminded of Richter’s

fondness for this composer’s works, so often underrated and deemed

appropriate study fare for ‘intermediate’ students only.

I

caught very little of the introduction to the moody and pained Largo

e Mesto (followed by the Menuet & Trio) of Beethoven’s Sonata no. 7

in D major, but again, this was irrelevant, since it was all there

in the music. The second movement of this sonata has been described

as Beethoven’s

first sojourn into the tragedy of existence, and Hadjinikos conveyed

to us not only every subtle shade of the composer’s melancholy

mindset, but also the beauty of the music born from it.

There was no ‘prologue’ to the Brahms Rhapsody in G minor which came

next – actually, I had felt a little disappointed when I saw it on

the program, wasn’t this the kind of piece that led people to

misunderstand Brahms’ music as ‘heavy’? But clearly this was because

I had never heard the Rhapsody played quite like this before,

without a trace of the Sturm & Drang style most pianists

bring to it, completely devoid of all haste and more intense than

ever – I wish there were a recording of this.

Much the same is true of the momentous interpretation of one of

César Franck’s last compositions, the epic Prelude, Aria and Finale,

which followed the interval. Before he set out on this separate

voyage within the evening’s journey, and following an anecdote about

how popular Franck’s music was in pre-war Greece – in his youth, the

poet Angelos Sikelianos had once asked him to play Franck for him,

saying that this was the only music he listened to - Hadjinikos

mentioned that to him, the Aria was essentially a prayer…and nothing

could have been more fitting. His performance was perhaps less

technically disciplined than lyrically delicate, but most important

was his sensitive touch – exactly what is required to rekindle

listeners’ appreciation of this masterpiece. It was not difficult to

deduce from Hadjinikos’s next introductory lines that he is

particularly partial to Debussy and the completely new approach he

devised to harmony and the flow of music, as well as his ability to

convey the feeling of eros in the pure sense, which he chose

to demonstrate with Preludes no. 1, 8 and 10, while closing with

‘The Joyous Island’ - and Grieg’s Lullaby as an encore, in view of

the late hour, as he remarked half jokingly (and indeed it was

almost midnight).

Throughout the evening, it was as if he

were playing to each member of the audience personally; intent on

conveying his message of humanism, he focuses on the significance of

music for humanity, for each and every individual listening to him,

and expresses what cannot be put in words.

I

left the recital longing to get home and play some of these pieces

myself, and wondering whether this feeling of discovery was anything

similar to what it must have been like for Hadjinikos when he

happened on those lost Skalkottas* manuscripts in a second-hand

bookshop in Berlin.

Bettina Mara

*George Hadjinikos is an authority on Nikos Skalkottas, and

the author of a recent book about this 20th century Greek

composer (unfortunately available in Greek only to date). The

complete opposite of an academic treatise, the footnotes are almost

more engrossing than the main text. Hadjinikos chose not to play

Skalkottas at this recital, attesting to the fact that, fortunately

for his audiences, self-projection is not an issue for him. Read

more about this artist at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hadjinikos

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page