Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Enescu, Oedipe

(Second Opinion)

: Soloists,

Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse; Capitole Toulouse and Bordeaux

choruses. Conductor: Pinchas Steinberg. Théatre du Capitole de

Toulouse. 10.10.2008 (ED)

There is little doubt that Nicolas Joel’s enthusiasm for the opera

has been a driving force behind the new production. It was

therefore, a great concern to learn of his serious health

problems in the run-up to the premiere, knowing that such a complex

work to stage might suffer as a result. On the evidence of the

opening night it seems perhaps that things were pared back to make

the production reach the stage on schedule, and perhaps before it

transfers to Bucharest next September further elaboration of the

basic concept might take place. The direction of Act I (Oedipe’s

birth and the prophecy of his downfall) had stuttering moments and

Act II (the killing of Laios and the answering of the Sphinx’

riddle) had more of them as the transfer between scenes seemed a bit

hesitant. Acts III and IV (respectively, Oedipe learns that he

fulfilled the prophecies and blinds himself before taking refugein

old age within a sacred grove with

his daughter Antigone), being both single scene acts had a greater

degree of cohesion about them. The use of a single set, with slight

variations, simplified things rather on stage as well. The massed

crowd scenes of Acts I and III worked well, but the setting of Act

II, scene 2 where Oedipe kills his father at a crossroads was ill at

ease with the raked amphitheatre setting

in which it found itself.

The shepherd’s horrific observation that the King and his two

companions were killed also failed to correspond with the action,

with only Laios lying dead on stage. Some might also have wished for

greater colour contrast between the grey-taupe set and the costumes,

which tended to instil a sense of dry dustiness to the legend.

The real beneficiary of the production though was the music, and no

doubt as a conductor himself, Joel

realised that this is where the emphasis should be. There is after

all enough musical detail in Enescu’s score which deserves its

chance to be heard, and not become swamped by stage action. A huge

orchestra including additional piano, harmonium, celesta,

glockenspiel, alto saxophone - and

for purely dramatic effect also including

a musical saw, wind machine, whip on drum, pistol shot and

a nightingale’s song -

is employed, but all are used

with a great deal of restraint. This is further augmented by mixed

adult and children’s choruses to add specific textural nuances to

the narrative. If extravagance was ever a good thing in opera, and

surely it is here, then this and the consequent demands made must

account of the lack of productions. Pinchas Steinberg marshalled the

forces effectively, rarely letting the tension drop, though I felt

there were aspects of transition that had yet to be effectively

realised: from the sense of gloaming before the riddle of the

Sphinx, through the interrogation itself, to the euphoric Theban

celebrations afterwards. Cristian Mandeal (conductor of the

Edinburgh, Cagliari and Berlin productions) brought greater

instrumental drama and weight to Oedipe’s blinding in Act III, and

certainly a greater understanding of the Romanian folk elements that

pepper the score.

Sylvie Brunet as Jocasta

The work has had a patchy performance history to say the least. From

its world premiere in 1936 at the Palais Garnier in Paris, which the

composer described as being “like a dream” because no sooner had the

work been presented then it disappeared almost from view, concert

performances initially filled the void, including those in Belgium

in 1955, and more recently in Barcelona during 2003. The

British premiere of was given in concert at the 2002 Edinburgh

International Festival. Staged performances of the work have long

been a mainstay in Bucharest, understandably, but internationally

only a few provincial German houses mounted the work, albeit with

significant cuts to the score, until the Götz Friedrich

co-production between the Vienna State Opera and the Deutsche Oper

Berlin appeared in 1996. The Teatro Lirico di Cagliari mounted a

modern dress production by Graham Vick in 2005 as the Italian

premiere. This new co-production by Nicolas Joel between Toulouse

and the International Enescu Festival is further evidence that

Enescu’s mature compositions continue to gain serious attention

before the public.

There are

unconfirmed rumours that the production might be seen at the Palais

Garnier in Paris during the 2010-11

season, as Joel assumes control of Opéra

de Paris in September 2009.

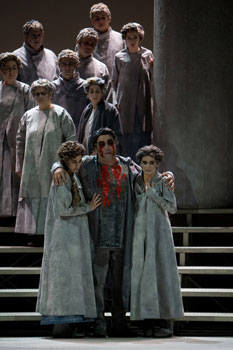

Oedipe Blinded

Any slightly negative points though were amply balanced by other

factors in the production. Effective lighting, though sparingly

applied, added emphasis at key moments: the Sphinx rising from her

hell-red pit to have infinitely more menace than in the Cagliari

production; or the brilliant blue present almost throughout the

final Act. The crowd scenes were handled well: the sense of decay

and desolation that pervades Act III and its contrast with the

transformation of Oedipe in Act IV as he fearlessly follows the

calling of Eumenides to the afterlife were effectively communicated.

The Sphinx

Oedipe is on stage more or less throughout Acts II, III and IV, and

it is a demanding yet beautiful role to sing for an artist

who has the necessary vocal resources for

the task, which by and large Franck Ferrari does. There was a slight

tendency towards inaccuracy, particularly in Act III when quarter

and three-quarter tones are used to heighten the sense of anguish

and self-torment that Oedipe feels.

Ferrari's acting was purposeful

throughout, if occasionally lacking somewhat in impetus. Much of the

rest of the cast benefitted by being native French speakers. Vincent

Le Texier portrayed Creon somewhat as an opportunist

and Emiliano Gonzalez Toro was an effective shepherd, the one

character who pieces

together the action from birth predictions to witnessing their

fulfilment. Arutjun Kotchinian provided a rich and menacing Tiresias,

dominating as much by his stage presence as vocally. Amongst the

female cast, Sylvie Brunet provided a

strongly acted and vocally robust yet heart-moving Jocaste, charting

a path from serenity at her new birth to inner-most terror before

her suicide. Amel Brahim-Djelloul’s Antigone was a plaintive foil to

Oedipe in the final Act. Marie-Nicole Lemieux would have stolen the

evening for many though, in her

single scene as the Sphinx. Although restricted in movement by her

deathly-black costume she used the full extent of her supple

contralto to bring both haughtiness and harrowed agony in the

moments of her death, as Oedipe confidently declares that Man in

stronger than Destiny.

It is this message that makes the opera a truly universal one, its

point highly necessary now in today’s troubled world,

and thus making Enescu’s music more

relevant to audiences than ever before.

Youtube: Video about the production

Pictures © Théatre du Capitole de Toulouse

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page