Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Second Opinion.

Mussorgsky, Boris Godunov:

Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera,

Conductor, Vassily Sinaisky, War Memorial Opera House, San

Francisco. 2.11.2008 (HS)

Probably no other other opera has gone through as many revisions,

re-orchestrations, re-sorting of scenes and acts and other

adaptations than has Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. Right from

the beginning, the composer himself went back to the drawing board.

The Imperial Theater rejected his original 1869 version, noting

among other things the lack of a significant female role. By 1872

the composer had reworked the seven existing scenes and added an

entirely new act set in Poland, where the princess Marina decides to

use a pretender to the throne as her path to becoming queen of

Russia.

Musically, Mussorgsky ends several scenes abruptly, the music

stopping suddenly rather than reaching a climax or arching into

rest. The curtain comes down for the one intermission at the end of

the scene at an inn, where the drunken friar Varlaam and his pal

Grigory, the pretender, are pursued by the tsar's guards. Despite

the vivacity and comic elements of the scene, it ends so

unpreparedly that only the drop of the curtain cued the audience to

applaud.

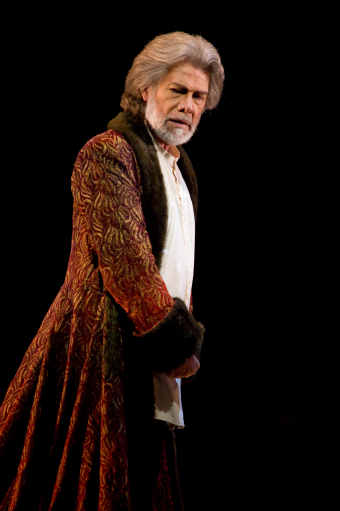

Boris Godunov – Samuel Ramey (bass-baritone)

Prince Shuisky -

John Uhlenhopp as Prince (tenor)

Grigory/The

Pretender Dimitri - Vsevolod Grivnov (tenor)

Varlaam - Vladimir Ognovenko (bass)

Pimen - Vitalij Kowaljow (bass)

The Simpleton - Andrew Bidlack (tenor)

Innkeeper: Catherine Cook (mezzo-soprano)

The Act I Set

The stark scenes in the original more single-mindedly focus on a

dark, brooding portrait of the troubled tsar than the grander, more

epic-scaled opera we are accustomed to. By the time the original

version finally was staged in 1928, several posthumous revisions,

culminating in a colorfully orchestrated one by Rimsky-Korsakov, had

changed Mussorgsky's tight, no-frills portrait into a grand opera.

This time around, San Francisco Opera mounted a strong, musically

and dramatically moving production of the original version, never

seen here. (In fact, Boris hasn't held the stage at SFO since James

Morris assayed the role in 1992.) One can argue that the later

versions are more complete, and the revisions to the original scenes

make them play more smoothly, but the original has a power of its

own: owing to a more economical palette of music and dramatic

material and that single-minded focus on what's going in in Boris'

mind without the distractions of colorful Polish balls and extensive

scenes detailing plots against him. Instead we can follow Boris'

disintegration from his accession to the throne through his growing

madness and eventual death.

Samuel Ramey as Boris

This economy, however, gives the scenes a certain realistic power,

the sense that we are encountering actual reality instead of a staging of

it. In its way, this series of individual moments is affecting. The

first two scenes, in later versions making up the prologue, show a

crowd of peasants being asked to pray that Boris will accept the

throne, followed by the coronation scene with the "slava" chorus and

Boris' prayer. Then we cut to the monk Pimen's cell, where he

recounts Boris' murder of the heir and Grigory decides to become the

pretender. Then comes the scene at the inn. After intermission we

get the scene in which Boris' monologue, wherein he sees the spectre

of the murdered heir, then the scene of in which a simpleton

confronts a frightened Boris, and the final scene of Boris'

confrontation with Pimen and his death. End of opera. No Polish act,

no Kromy Forest scene.

Some of the music we associate with Boris' big set-pieces had not

yet been written for this score. But Samuel Ramey, in the title

role, grabs hold of the material and gives us a portrait of a man

haunted by his past deeds (having killed the heir to get the throne)

and, in his dying moments, urges his son to keep his conscience

clear in order to be a good ruler. At 66, Ramey can occupy a

character with mesmerizing intensity and wield a gloriously dark

bass-baritone. The wobble that has affected him in recent years

stayed more or less in check in Sunday's performance, but a

prominent dynamic beat on the correct pitch, especially in his

mid-range, could be off-putting. At the top or the bottom, or in the

big moments, he can still pull it together to achieve astonishing

power.

The cast was strong across the board, both vocally and dramatically,

especially bass Vitalij Kowaljow as Pimen, bass Vladimir Ognovenko

as Varlaam and tenor Vsevolod Grivnov as Grigory, the pretender. As

The Simpleton, first-year Adler Fellow Andrew Bidlack appeared in

virtually every scene. Bald, cradling a model of an onion-domed

Kremlin tower, he roamed the stage, interacting mutely with other

characters, until encountering Boris in the penultimate scene. His

disturbing presence and clear, pure tenor made for strong theater.

Vassily Sinaisky, chief guest conductor of the BBC Philharmonic who

recently led performances of Carmen and Der Rosenkavalier

at English National Opera, was strongest in the more intimate

moments. The big crowd scenes never quite erupted with their full

power, possibly because Mussorgsky's own orchestration was less

colorful than the more familiar ones from Rimsky-Korsakov and

Shostakovich. That only put more emphasis on Boris' internal

struggles, which is exactly what made this version so compelling to

watch.

Harvey Steiman

Pictures © Terrence McCarthy

Back to Top Cumulative Index Page