Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERVIEW

Howard Blake talks to Bob Briggs:

The composer of Walking In The Air turns 70 this month.

Bob Briggs discovers more about an extraordinary musician. (BBr)

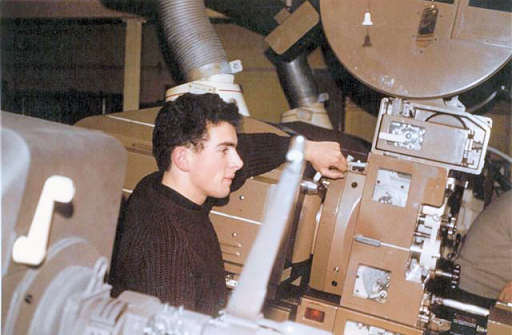

I was there for two and a half years. And it was wonderful and I

watched every film – all the great films and experimental films –

and the wonderful scores by Bernard Herrmann and Prokofiev and

Walton. And while I was there the Assistant–Chief Projectionist had

a 16mm Bolex camera and I said ‘Let’s make a film’. I wrote a script

and got the whole staff together, and we got all the stock for

nothing and we could edit it in the Projection Room after we

finished work. I made the film and I edited it and then I wrote the

music for it, recording the music with some of my friends from the

Academy. It was a very good film and it was shown in the National

Film Theatre and I not only produced and directed it but also

projected it! So I learnt a great deal from that period in my life.

I learnt about film, music, recording, I learnt a lot of skills

which I don’t know where else I would have learned them.

Promotional photo about 1969 ©Howard

Blake collection

PART TWO

“I left the Academy as a total washout. And I hung around for a bit

and I was living in Brighton and I wrote off to the BBC and Sadler’s

Wells, and I wrote to all sorts of people to try and get a job. I

never got a single answer! I got a job for two weeks as a hotel

porter in Brighton, at the Adelphi Hotel. I was absolutely useless,

I couldn’t serve a drink, turn the television on or do anything! The

Manager said, ‘What’s an educated person like you doing here?’ and I

said ‘I’m trying to earn a living’ and he said, ‘well I don’t think

you can do it here!’

I then saw a job advertised in the Brighton Evening Argus –

Assistant Projectionist wanted, Paris Cinema, Brighton. And can you

believe it? They’re showing both parts of Ivan the Terrible.

I thought, ‘I haven’t got any money, if I got the job I could see

Ivan the Terrible!’ I walked round and said I wanted a job,

and they said, ‘yes, experience?’ And I said I went to a film

school, the British Film Institute last summer, so he said we’ll

give you a try and I got the job. I did that for a number of weeks

and it was terrific. I was a terrible projectionist but I gradually

got the hang of it. And then I thought I should go to London and I

slept on someone’s floor for several days, and during that first

week I was in London there was advertised, in the Evening Standard,

Assistant Projectionist wanted in the National Film

Theatre [now re–named the BFI on the Southbank] which was my

Mecca. So I went along, said I had some experience and I got the

job.

This film made quite an impression and the BFI said ‘we’ll give you

a grant to study and become a film director.’ But I’d done this job

and I said, ‘well I’ve got to earn some money’. I thought that being

a film director is not what I am. I’m not actually interested in the

visual, I’m only interested in the music and I want someone else to

do the visual. What’s fantastic about film is that it uses music of

every sort imaginable; jazz, pop music, what they now call world

music, folk music and I found that fascinating because it was

outside the world of the Third Programme [the BBC’s cultural radio

channel which, in 1967, became what is now known as BBC Radio 3] at

that time. The films came from Japan, Argentina – from all over the

world. Everything had music and I felt fascinated by that and I felt

I wanted to learn more about other sorts of music but I thought that

I didn’t know how to do that and make a living.

I saw another advert in Stage which said ‘Pianist wanted at

pub, £4 a night’. I got £13 a week as a projectionist and £4 is £28

a week if you work seven nights. I didn’t know anything about

how to play jazz I only knew about classical music. I got the job in

a pub in Edgware Road, and I was terrible. Someone poured beer over

my head and said, ‘you mean to say you can’t play Lady is a Tramp?’

I just had to learn every tune that ever was. So I created for

myself a routine – I would learn ten tunes a day by listening to the

radio and records. I wrote them all down, and I gradually got very

good. And this pub, after a while, was absolutely packed out and

people would come for the music. There were so many people outside

that one Saturday night the police had to come and disperse them!

Really that was also a second piece of training, I discovered what

people like, and what they don’t like.

Here

Blake had to use all the skills he’d learned whilst playing in the

pub as he was given music and asked to play it, at sight.

“Can you improvise in jazz, can you play from chords, can you

play classical? Yes, that was no problem. I became a session pianist

at Abbey Road. It was fantastic. I went from £20 a week to £200 a

week overnight!”

With all this activity I assumed that Blake wasn’t writing his

own music because he simply didn’t have sufficient time for

composition.

“Funnily enough, whilst I was in the pub, I never stopped

writing, all that period I had written stuff, and I started writing

a Symphony which I called Symphony in One Movement. I worked at

that, on and off, as well as learning to play Lady is a Tramp. I was

playing innumerable sessions and I was playing for film sessions,

and I got to work with Bernard Herrmann. By that time I’d started

scoring stuff for people, and I scored some stuff for Bernard

Herrmann. I started conducting – I conducted for Quincy Jones – I

worked with Henry Mancini, very good people.”

Blake told Herrmann, who was desperate for recognition as a

composer for the concert hall, that he had written a Symphony

and Herrmann said that he would like to see it.

“I

took it along and I showed him this piece. He said, ‘it’s terrific.

Does the BBC play it?’ I said ‘they won’t touch anything like that,

it’s all squeaky door or nothing’. He said, ‘You should be writing.’

One of the jobs I did was playing piano for the soundtrack of the TV

series The Avengers [which starred Patrick MacNee and Diana

Rigg]. Laurie Johnson, who wrote the music for the series, was

looking for somebody to take over, writing some episodes because he

was too busy and due to Bernard, Laurie gave me a job scoring and

conducting some episodes. I suddenly stopped

being a pianist at Abbey Road and became a composer. In that moment

I was being paid as a composer, as a conductor, and as a musical

director. In a very short time I’d moved from being a hotel porter

in the Adelphi Hotel to musical director at Elstree [the film

studios situated in Borehamwood, in Hertfordshire, north of London]

– in three or four years. I have never, ever, stopped writing music

from that moment on. How

did I start to write classical music? That’s the question.”

Just

as I was looking forward to an answer to this question I

inadvertently mentioned music for film and Blake eagerly waxed

lyrical about writing for the cinema.

“Writing music is writing music and there are ways of writing each

sort of music. Why I think pejorative terms are used about film

music is that a great deal of it has to happen at a very low

temperature because people are whispering or walking round rooms

talking to each other and traffic is going by and dialogue is going

on. All Film Directors want is big fat semibreves going on, on

cellos, and they don’t want anything else. When you play that back

as music, it can’t, in all honesty, be described as proper music. It

is a particular technique of sustaining the correct atmosphere.

Sometimes, of course, one is called upon to write an intensely

active piece of music and sometimes, rarely, one is asked to write a

really good piece of music. On the whole one is not! I am

actually

not a good film composer. I’ve done 65 films. I’m not a good film

composer because my scores have frequently been thrown out because

they’re too good! They say, ‘You’re trying to take over the film!’

I

nearly got murdered because of this. I did a film called Agatha,

I was Musical Director on it. David Puttnam was the producer and he

said, ‘It should be like a big Max Steiner score. It’s 1923. Period

film. Huge orchestra. You can do it. The actual script is a little

bit iffy, a little bit weak, so we shall have to rely on the score a

lot, so give it all you’ve got Howard.’ So I wrote a big score for

it but David backed out of the film and we got another producer in who

hadn’t the same idea. We had a preview at BAFTA in Piccadilly

[in central London] and everybody was saying, ‘What a wonderful

score.’ Everyone had questionnaires and everybody put ‘fantastic

music’. What do you think of the script? Lousy. What do you think of

the acting? It’s OK. This producer grabbed me by the throat, and he

said, ‘What are you trying to do? We’re not asking people to buy

your bloody music. We want them to buy the film. We’re going to junk

the whole lot’. And he did. Junked the entire score. About one hour

of fully scored, symphonic music, gone, like that. That’s happened on

a number of things. So it’s a high risk job.”

“I

don’t really know how to answer that. Sometimes you’re lucky. In

fact, my collaboration with Ridley Scott and David Putnam, on The

Duellists (1977), was terrific because we talked about the music

at every stage and they wanted a good score. In a way you’re brought

in like someone who paints a wall. Decorates a flat. They say, ‘This

is our flat and we want you to paint that wall bright pink.’ And you

say, ‘You’ve got to be kidding’ but if you want to keep your job you’re

going to paint that wall bright pink. You’re the composer and you’re

actually a servant. Even more so than, say, Haydn was. You are at

the beck and call of the Film Director and the Producer. They say,

‘This should sound like Stravinsky, this bit should sound like Burt

Bacharach’. They blatantly ask you to plagiarize and they’re not

interested. They just want it to do a job. And so it’s a very odd

thing to do, to write film music. Nowadays, more and more, they use

records and they use “found music”. They put stuff together on

synthesizer and they actually take big chunks of Stravinsky and weld

them together with the Beatles and stick them all on the synth and

that’s it.

So it’s really become less of an interesting job to write

film music than it used to be. One of the reasons the art of writing

music for film has been lost is that the music business gradually

started to click on to the fact that there’s a lot of money in

having music on films and the film can actually promote the music

- so the

whole pop business is trying to get its product of pop music stuck

onto films. That’s changed the way music scores happen. Whereas in

the early days of film music, when people like Herrmann started, the

composer was asked to write a complete score and he was given a free

hand. And they’d say, ‘Well we trust you to do a great job on it’.

Like Psycho, for instance, which is still one of the greatest

film scores ever written. I gradually retired from films because I

had a number of bad experiences but also because I was too busy

writing classical commissions.

“Funnily enough, I actually turned down Barry Lyndon (1975)

in order to write my Piano Quartet. I was really not

available. I think a great many composers in the 20th

century had this problem. The only way you can make a living is

writing for films or television. And yet most people want to write

“serious music” but there’s no money in it. So you have this dilemma

about how do we get around that? The autobiography of Miklós Rósza

is called A Double Life and many people have done that. I

decided, in a way, not to live a double life. I decided that, for

me, all music is music and if I wanted to write a film, if it’s a

good film I’d write it and if I wanted to write a concerto, I’d

write a concerto. I think it’s daft to say I’ve got one style that I

use for films and another style when I write concert music. All

these people like Miklós would write this great music for film and

then they would try and write something that was considered more

avant garde which still sounded exactly like the film music. So who

are you kidding?”

By

this time Blake had become well known through his commercial work

and when he made the bold move into the concert hall, leaving the

cinema behind. I wondered whether, what with the Darmstadt school and serialism

at its height and with William Glock presiding over music at the

BBC, Blake - complete with his belief in tonality and tunes - had

had trouble

getting performances.

“Yes. Totally impossible. Through the ‘60s I gradually built myself

up through The Avengers and doing feature films and so on.

The second really big defining moment in my life was about 1970 when

I was just unbelievably busy writing commercial music, and

unbelievably successful too. The downside was that I couldn’t live

with myself. And I started to shake, I started to feel I can’t keep

writing this stuff and I didn’t know why I couldn’t. Everybody said,

‘Well you’ve done it. You’ve made it. You’re writing for films,

you’re writing for television. Everybody wants you’. I went to see

this Doctor one day and he said, ‘Put your hand out’, and it shook…”

Here

Blake held out his right hand and shook it furiously.

......and he

said ‘put the other hand out…’”

The

same demonstration is carried out with the left hand.

“And

he said, ‘Oh yes, you’re going to be dead in five years. You’re just

not doing what you want to be doing. You’re speeding. You’ve got to

calm down and think about what you’re doing’. So I dropped out, went

down to Cornwall and sat on a beach. I did a great deal of thinking

and I thought, ‘Actually, I do want to be a composer. I want to

write music more than anything in the world’. And I thought if I

don’t do it now I’ll never do it. I thought, ‘I’m going to give up

this whole situation and I’m going to start again and I’m going to

learn to write classical music. And I really don’t care what the BBC

or anybody else thinks because I don’t care if anybody wants to

listen to it or not. And if the BBC doesn’t want to play it that’s

their hard luck’. And rather like when I decided to go and play in

the pub I thought, ‘I don’t care what anybody thinks, I’ve got to

play music again. If it means playing in a pub then I’ll play in a

pub. I’m going to write my own music’.

I left London and went down

to the country and I thought of enrolling in a University. I tried

several and said I want to learn form and counterpoint, absolutely

strict Palestrina–type counterpoint. I want to write contrapuntal

music, I want to write proper music. The essence of music is

counterpoint. I could do it, I just wanted to get better at it.

Finally, I decided to study on my own and I used to get up every

morning and do counterpoint exercises - for about five years. And I

looked at form, I really studied form, particularly in Beethoven,

who is the guv’nor of all time. Absolutely no question. I also

studied a lot of Stravinsky, a lot of Mozart, Schubert. All the

great classical composers. That is when I wrote the Piano Quartet,

the Diversions for cello, and in fact the Violin Sonata

which I’ve just finished thirty five years later. I started writing

stuff and locally I was asked would I like to do a concert. I did a

concert in a barn.

My friends,

some very good players, came down from London. We did a concert in a

hall belonging to the local lunatic asylum and Janet Cannetty–Clarke

the conductor of the Ditchling Choral Society said, ‘Would you write

a piece for us?’ I wrote a cantata, The Song of St Francis,

and it was performed in that first concert with piano accompaniment

only. It was quite a success and she asked me if I would score it

for orchestra, since they were shortly to perform Mozart’s Requiem

in the nearby Benedictine Monastery, Worth Abbey. I scored the

cantata for the identical instruments used by Mozart for his Requiem

and it sounded great! Richard Lewis, the greatest oratorio tenor of

his time, and the Abbot of Worth, Victor Farwell, and Janet Cannetty–Clarke

were all delighted with the work and asked if I would consider

composing a full scale oratorio. Richard Lewis said, ‘If you write

it as a demanding work, featuring solo tenor, I’ll sing the oratorio

for you.’ So, I put one foot in front of the other and started

writing and people said, ‘This is marvellous’. BBC Brighton recorded

and broadcast it. The producer was Jim Parr and a bit later he said

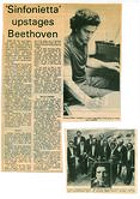

to me, ‘We’ve got the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble coming down for

the Brighton Festival, could you write a work for them?’ so I wrote

Sinfonietta for Brass and it was performed in St Peter’s

Church together with some Beethoven. The local paper said ‘Local

Composer upstages Beethoven!’

“But I never

stopped doing any of the other things. I was still doing film, and

then I started doing ballets for Sadler’s Wells and for London

Contemporary Dance. I was suddenly invited to Hollywood to write a

film called SOS Titanic. I went over for three months, came

back and finished scoring the oratorio.

“It’s just all

music. It doesn’t matter. If it’s serious I’m writing serious music,

if it’s not serious I’m writing not serious music.”

Bob Briggs

Part Three

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page