Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Festival d’Aix en Provence (2): Mozart,

Zaide:

Soloists, Camerata Salzburg. Conductor: Louis Langrée. Théâtre de

l’Archevêché, Aix en Provence, 5.7.2008 (MB)

Zaide – Ekaterina Lekhina

Gomatz – Sean Panikkar

Allazim – Alfred Walker

Sultan Soliman – Russell Thomas

Osmin – Morris Robinson

Peter Sellars

(director)

Georges Tsypin (designs)

Gabriel Berry (costumes)

James F. Ingalls (lighting)

Ibn Zaydoun Chorus (director: Moneim Adwan)

Camerata

Salzburg

Louis Langrée (conductor)

That Zaide is a problem piece, no one would deny. The music

is far too good to lie unperformed but it is frustratingly

incomplete: something clearly must be done. It seems to me that

there are three principal paths one could take. One could make a

virtue of the incomplete nature of the ‘work’ as it stands, either

by taking up and developing the theme of fragmentation. One might

commission some new music and either provide it with a

companion-piece (as the Salzburg Festival in 2006 did) or transform

it into a new work. Or one could attempt to make it cohere as it

stands, perhaps by adding further music by Mozart. The incidental

music to Thamos, King of Egypt is a favoured candidate for

this approach, and this is what happened here. Except that it did

not. There was at root a glaring contradiction, perhaps resolvable

or perhaps not, but certainly not resolved in this particular case,

between a quasi-traditional path of Mozartian completion and

Sellars’s understanding of the work.

There is nothing wrong in principle with providing a work with a new

or modified message, although it needs to be done well – and rarely

is. Sellars, however, actually seems to believe that Zaide

itself is about what he decided to put on stage. I can say this with

some confidence by virtue of his comments in the programme. Take the

following extract from his ‘synopsis’, informing us what is going on

in that most celebrated of the work’s arias, ‘Ruhe sanft’: ‘From her

sewing machine above, Zaide (a Muslim) hears Gomatz struggle. She

sings a lullaby to ease his pain and lowers her ID card to him,

hoping her picture will bring him comfort and strength…’ Or this

commentary on Osmin’s ‘Wer hungrig bei der Tafel sitzt’: ‘This

escape is not a problem for Osmin. As a slave trader, his speciality

is outsourcing and there is an endless supply of desperate people

who will work under any conditions. From his point of view, Soliman

is behaving like one big fool. Modern management techniques offer a

huge profit from a disposable work force. The lesson is: if there is

food, eat your fill.’ For Mozart, Sellars tells us, ‘belonged to a

generation of artists, activists, intellectuals, and religious

leaders who dedicated an important part of their œuvre to the

abolition of slavery.’ This, apparently, is what the Enlightenment

was about. Except it was not – and nor is Mozart’s unfinished

Singspiel. Mozart was not the egalitarian Sellars explicitly

calls him. A little while after composing the music to Zaide,

Mozart dismissively reported to his father of Joseph II’s inclusion

of the ‘Viennese rabble’ (Pöbel)

at a

Schönbrunn ball. Such rabble, he wrote, would always remain

just that. This does not place Mozart at odds with the

Enlightenment; it places him at its heart, along with Voltaire’s

plea to his guests not to discuss the non-existence of God in front

of the servants, lest the latter should forget their place. And as

for the American plantations… The Enlightenment in general and

Mozart in particular are far more complex than a modern, liberal

American mind – or at least this one – appears able to comprehend.

Hierarchy is sometimes undermined in Mozart’s operas but never to

the extent of threatening the social order. Le nozze di Figaro

is, after all, but a ‘folle journée’, from which most of

Beaumarchais’s menacing rhetoric has been expunged.

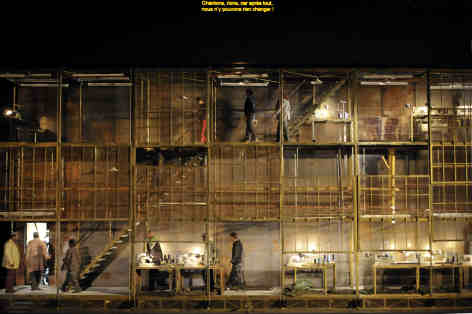

It gets worse however, when Sellars comes to staging this

misunderstanding. (Some misunderstandings can be fruitful, but not

this.) Zaide takes place in a modern sweatshop, replete with

the ‘ID cards’, ‘modern management techniques’, and so on, which I

quoted above. Somehow the issue of Palestinian liberation becomes

embroiled in this issue and that more broadly of modern slavery; it

is all about ‘freedom’, I suppose. I hope that it should not need

saying that I abhor all forms of slavery, ancient and modern,

including the repression of Palestine, but that does not in itself

make the issue relevant to an unfinished work which is about

something quite different, nor to a production which, through its

generally ‘right-on’ contradictions, cannot make up its mind what it

was really about. We therefore had a ‘chorus’ of six modern slaves

traipse on to stage following the appropriated ‘overture’, for an

oud – I think – to strike up by way of introduction to the harmless

little song they presented. Mozart was then permitted to return,

providing different music to what I believe were the same words. We

never heard again from the Ibn Zaydoun chorus, associated with the

admirable organisation Esclavage Tolérance Zéro, nor from the

chorus’s director, Moneim Adwan. Their inclusion was offensively

tokenistic and added nothing to the botched drama on stage; they

sang well enough in an amateur fashion. The Aix audience was made to

suffer ever so slightly by the turning on of glaring strobe lighting

at the ends of musical numbers: irritating enough to be

discourteous, and obscene if the suggestion were that we could in

any sense thereby participate in the very real agonies of modern

slavery, be it in a sweatshop or the Gaza Strip. East-West tension

might fruitfully have been addressed in a work such as this, but

here it was not.

Camerata Salzburg sounded as it generally does nowadays,

post-Norrington. Sándor Végh would turn in his grave to hear the

low-vibrato, short-bowed, small-in-number (7.6.5.4.2) string

contribution, although there were moments when the section was

allowed greater musical freedom. The opening bar confronted us with

the perversely rasping sound of natural brass and with the

‘authentic’ bashing of hard sticks upon kettledrums. It was left to

the superlative woodwind section to provide Mozartian consolation.

Louis Langrée drove the score quite hard, sometimes with dramatic

flair, often with a harshness that has no place in Mozart. He was

able, however, to provide considerable dramatic continuity both

within and between numbers. Perhaps surprisingly, the Thamos

items often fared better. There were some promising young voices on

stage, although they had a tendency to present excessively

broad-brushed, unshaded interpretations – and were sometimes just

far too loud. Sean Panikkar possesses a winningly ardent tenor,

which impressed more in the first than in the second act. Thankfully

he had more to do in the first. Alfred Walker was dignified earlier

on but subsequently unfocused. What were we to make of Ekaterina

Lekhina in the title role? She delivered her second act arias rather

well, but was all over the place in ‘Ruhe sanft’: tremulous and

out-of-tune in an almost caricatured ‘operatic’ fashion. More

worryingly, why was she, a Russian soprano, included in what was

otherwise clearly a purposely-selected non-white cast? I cannot for

one moment imagine that this was the intention, but I almost had the

impression that here was a white woman, threatened and surrounded by

coloured men. Whatever the actual intention was, I am afraid that it

entirely eluded me. The impression of abject incoherence was

nevertheless intensified still further. I think that I have now said

enough.

Mark Berry

Pictures

©

Elisabeth Carecchio

Back to Top Cumulative Index Page