Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD CONCERT REVIEW

Messiaen ,

From the Canyon to the Stars :

Pierre-Laurent Aimard, (piano),

Jean-Christophe Vervoitte (horn), Samuel Favre (xylophone),

Michel Cerruti (glockenspiel), Ensemble Intercontemporain, Susanna

Mälkki (conductor), Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, 2. 2.2008 (AO)

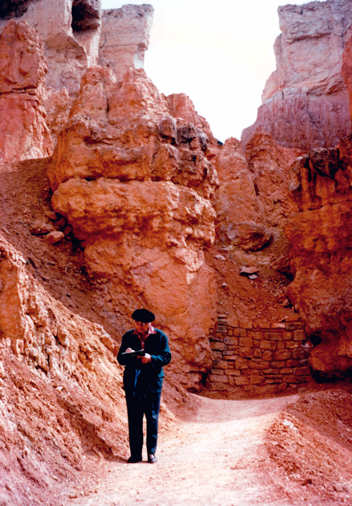

Olivier Messiaen at the Grand Canyon

Ensemble Intercontemporain was founded in 1976 by Pierre Boulez to

specialise in new music. Aimard was in fact one of the founder

members. Because its musicians are virtuosi in their own right,

the orchestra’s philosophy is well suited to Messiaen’s music,

where clarity of instrumentation matters so much. Each detail in

music like this needs to remain pure and distinct, not muddied.

Susanna Mälkki, the Ensemble’s new Music Director, is able to draw

out the best from her musicians while negotiating the complex

twists and turns that propel the trajectory.

This is no minor achievement. From the Canyons to the Stars

is two hours long, a series of 12 individual sections. It’s a

huge beast, but not a symphony in the traditional sense. Instead,

it’s a panorama of unfolding vistas. Bravely, Mälkki abandoned

the frequent practice of dividing the piece into two parts with an

interval. Yet, this performance didn’t sprawl into loose

confederation because she hard such firm grasp of its inner

dynamic Messiaen observed birds not only for their songs but in

their movements. Sometimes birds creep quietly on the ground, but

they can sudden fly off unpredictably. That’s how they survive.

“Man hasn’t

been on this earth that long”, Messiaen said. "Before us there

were prehistoric monsters, but in between there were birds".

Canyons, of course, are even more ancient than birds or dinosaurs,

so they represented for the composer a force even more primeval

and closer to his God. Conventional symphonies have an inner

architecture like a skeleton. Instead, Messiaen finds a different

kind of structure, more organically based on observation of

nature. Thus Mälkki

intuited that this music works with an exoskeleton, for it is

these jerky changes of direction, and sudden leaps from noise to

utter silence, give the music its overall shape. This was a

perceptive approach which made more sense than trying to fit it

into a more obvious “logical” form.

Without doubt,

Mälkki is someone to watch, and may become one of the more

outstanding conductors of this generation. Last summer, at the

Proms, conducting Boulez and Birtwistle, she showed similar

intelligence. When she conducted Boulez’s Dérive II she

brought out its surprisingly powerful, organic lyricism. It seemed

to unfurl like a fern, each cell growing out of another,

developing and expanding. Messiaen’s influence on Boulez is

deeper than commonly assumed.

The twelve sections of the work revealed themselves as a

progression. Each section is built up from myriad details.

Significantly, the smallest instrument in the orchestra, the

piccolo, plays an important role, just as the smallest bird in a

dawn chorus can be heard distinctively.

The third section, Ce qui est écrit sur les étoiles is

built around massive, angular blocks of sound. Before the

concert, Mälkki had spoken about the “shape” of Messiaen’s work

being as valuable as the colours, so often assumed to be the basis

of Messiaen’s music. The Ensemble produced blocks of sound,

reinforced by detail like the “geophone”, a flat drum filled with

lead beads, rotated to sound like shifting dunes of sand.

Although it’s very graphic, it fits in with the overall palette of

sound rather better than the famous wind machine. Similarly,

Mälkki understood the upright and downward thrusts in the music,

evoking the craggy peaks and columns in the strange geology that

is Bryce canyon, but also Messiaen’s spiritual aspirations.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s two long solos in the 4th and 9th

sections were beautifully executed. For a moment, time seems to

stand still, while the piano does a “display dance” like a bird

showing off its plumage, and then the music progresses back to its

normal pace.

Jean-Christophe Vervoitte’s horn solo was spectacular. Again, for

a moment, Messiaen takes a break from the landscape as a whole,

focussing on an individual. The elaborate horn seems to be calling

across the desert, across time and space itself. It doesn’t get a

reply, even when it repeats itself more quietly, as if from a

distance. However, this serves to emphasise the isolation of this

landscape, and perhaps, the realisation that there isn’t any need

for a response from another terrestrial party, when one is in the

presence of the sublime.

The final section, Zion Park et la cite céleste, evolves

naturally from what has gone before as dawn follows a peaceful

night filed with stars. There doesn’t “need” to be tension before

this glorious morning, for in nature, day naturally follows night,

eternally, regardless of what happens in the world. Struggle is a

“human” value but humans are irrelevant in this landscape. Hence

the dawn chorus imagery returns in glory.

Glockenspiel and

Xylophone are “dawn chorus” instruments par excellence, many

individual parts working in unison yet without blurring. The

ostinato angles in this section act like apostrophies urging the

music onwards, rather than interrupting the flow. The whole

ensemble joins in a riotous crescendo of unalloyed joy. What a

nice conclusion to the first part of this excellent South Bank

festival.

Anne

Ozorio

Picture courtesy of the South Bank Centre

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page