Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Britten: Peter Grimes

(new production premiere):

The Metropolitan Opera and Chorus,

Soloists, Donald Runnicles (conductor), John Doyle (production),

Scott Pask (set designer), Ann Hould-Ward (costume designer),

Peter Mumford (lighting designer), Donald Palumbo (chorus master),

New York, 28.2.2008 (BH)

Having a crowd stare at you for three hours is unnerving, and that

awkward—and powerful—image is at the heart of the Met's new

production of Peter Grimes, brilliantly conceived by

director John Doyle. What at first seems a handicap—the huge Met

chorus having little space to maneuver in front of designer Scott

Pask's enormous wooden wall—eventually becomes a strength, as over

and over the cast delivers their lines while glaring out into the

audience. The cast is as trapped in their environment as Grimes

is. Near the end, when the townspeople line up downstage and belt

out "Peter Grimes!" it chills to the bone; somehow this crowd is

after you. Doyle got it right: it's an evening of constant

accusation.

The first act has little in the way of action," and the blocking

consists of the crowd generally bunched in the center of the

stage. But by Act II Doyle's idea becomes uncomfortably clear:

Grimes is increasingly trapped in an enormous labyrinth of forces

well beyond his control. Windows and doors in the wall magically

open without a sound, revealing people standing, gazing out in

silent judgment, their ultimate intentions unknown. While I'm the

last person to encourage opera casts to simply stand in one place

and sing, here the idea works, with the cast functioning more like

members of a jury box.

Racette almost anchors the production, providing humanity and

heartbreak, and her big scenes—"Glitter of waves" in Act II and

the famous "Embroidery" scene in Act III—not only show her

lustrous voice but her piercing acting skills. Anthony

Michaels-Moore is equally astonishing as Balstrode, wanting to

offer Grimes consolation but ultimately forced to take other

measures. Fine work by Greg Fedderly as a drunken Bob Boles,

Bernard Fitch as the pious Rev. Adams and newcomer Teddy Tahu

Rhodes as a memorable Ned Keene all help etch a gorgeously sung

landscape.

Britten:

Peter Grimes (new production

premiere)

Conductor:

Donald Runnicles

Production:

John Doyle (debut)

Set Designer:

Scott Pask (debut)

Costume Designer:

Ann Hould-Ward (debut)

Lighting Designer:

Peter Mumford

Chorus Master:

Donald Palumbo

Cast:

Hobson:

Dean Peterson

Swallow:

John Del Carlo

Peter Grimes:

Anthony Dean Griffey

Mrs. Sedley:

Felicity Palmer

Ellen Orford:

Patricia Racette

Auntie:

Jill Grove

Bob Boles:

Greg Fedderly

Captain Balstrode:

Anthony Michaels-Moore

Rev. Horace Adams:

Bernard Fitch

Two nieces:

Leah Partridge (debut), Erin Morley

Ned Keene:

Teddy Tahu Rhodes (debut)

Boy:

Logan William Erickson

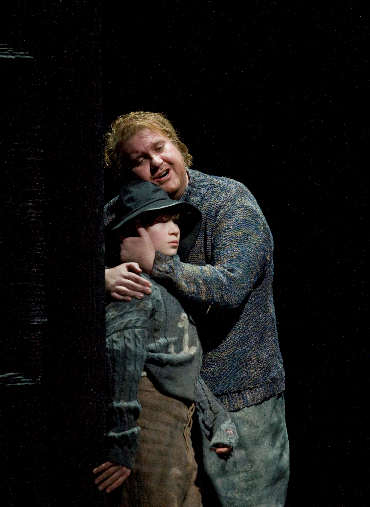

Peter Grimes: Anthony Dean Griffey and the Boy: Logan William

Erickson

At the heart of Pask's magnificent set design is the hulking front

wall, towering the complete height and length of the Met stage,

and built from rough, dark wood shingles modeled after huts used

by fishermen on the coast of England to store nets and fishing

tackle. I couldn't help but wonder if Pask admires the black wood

landscapes of sculptor Louise Nevelson. Equally essential is

Peter Mumford's lighting: when the wall slowly retreats, the glow

from above casts shadows, like moonlight splashing the shingles as

they come into view. Near the end, when Grimes is almost squeezed

between two buildings, the light hits the top edges, only

emphasizing the now impossible depth to which he has fallen.

The Set

Musically, I doubt anyone could ask for a more incisive traversal

of the score, conducted with sweeping confidence by Donald

Runnicles, and executed with great precision by the Met Orchestra

(whose members applauded the conductor during the ovations). The

orchestral interludes are presented with very little stage action

or embellishment, other than subtle lighting changes washing

across the wooden slats, and it's a good call: sometimes "only" a

sunrise is all that is needed. With gorgeous phrases flying

throughout the house like sea spray, there's nothing needed to

distract viewers from Britten's evocative mini-tone poems.

(Moreover, perhaps this will further encourage behavior changes in

some opera fans that feel that when no one is singing,

conversation is acceptable.)

So many cast members stand out it is hard to know where to begin.

Even smaller roles are ardently sung, such as Dean Peterson's

Hobson and John Del Carlo's lawyer Swallow, first in line in the

excellent cast. Felicity Palmer, whom I last saw clawing through

the floor in Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades, is like the

nosy neighbor you never want, always in your business and never to

your benefit. Jill Grove makes a winsome Auntie, and is part of

the extraordinarily haunting quartet in Act II, with the two

nieces (Leah Partridge and Erin Morley) and Ellen Orford, in a

dramatic turn by Patricia Racette.

Ellen Orford:

Patricia Racette

But the production ultimately rests on the title character, and

the superb Anthony Dean Griffey offers not only a complex

character, not easily fathomed, but couches it in some of the most

lyrical tenor work one is likely to hear this season. Griffey

makes Grimes' fate feel pre-ordained by forces larger than his

capacity to understand, much less overcome, and as a friend said,

he also seems more than a little hotheaded and crazy, to boot.

When he roughs up his new apprentice, played with cowering fear by

Logan William Erickson, it's actually a bit scary seeing him hurl

the boy into a corner. Or when Grimes sings the magnificent "Now

the Great Bear and Pleiades," let's face it: he basically

interrupts what appears to be a cracking good time in the pub,

dampening the mood with his soulful philosophizing. And if Grimes

didn't actually kill his apprentices, are their fates

coincidences? Just bad luck? Is "hanging around with Peter"

automatically a death sentence? Griffey's portrayal won't allow

any neat conclusions.

The members of the Met Chorus, increasingly agile and accurate,

are just sounding more marvelous every month under Donald

Palumbo. Britten has composed a chorus-heavy opera, and whether

in the intricate "Old Joe has gone fishing" or in the

aforementioned climax, the sheer power of the group carries the

music aloft like great oceanic winds. Doyle's vision deliberately

doesn't probe deeply into the psyches of the townspeople; they are

specks, tiny insects swept up by forces larger than they can

comprehend. Ann Hould-Ward's handsome costumes, in shades of

black, brown and gray, discourage treating them as individuals.

Their emotions are at nature's beck and call; the ocean and

weather rule their lives. These may be not literal fishermen but

figurative ones, and the opera may work even better as allegory.

Doyle seems awestruck by this possibility, and encourages us to

view it in the largest, most disturbing sense.

The opera's final scene will no doubt baffle some: after Grimes

has gone out to sea for the last time, the townspeople and cast

assemble downstage. Behind them the towering partitions glide

away to reveal a white-lit back wall and a large modern steel

structure with catwalks, upon which dozens of people in

contemporary dress pose, like silent slackers. (Or as one person

I overheard said, "An ad for the Gap.") Maybe I'm too charitable,

but I cut Doyle some slack here: their appearance and silence

acknowledge that Grimes's predicament is one encountered by

someone of every generation, and offers scant reprieve from the

idea that in some way we are all complicit.

(The Met's broadcast of

Peter Grimes will be on Saturday, March 15. More

information

here.)

All pictures

© Ken Howard

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page