Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- London Editor-Melanie Eskenazi

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL OPERA REVIEW

Robert Schumann, Szenen aus Goethes Faust:

(new production) Soloists, chorus, ballet and orchestra of the

Teatro Regio di Parma/Donato Renzetti conductor Parma,

Italy. 16.1.2008 (MM) Goethe's Faust is a two-part play intended to be read, not

staged, though in 2002 it was staged by Peter Stein within a mere

twenty-one hours. Schumann's Scenes from Goethe's Faust is

an oratorio meant to be performed in concert, unstaged again,

although its seven scenes were staged at the Teatro by Hugo de Ana

in three long hours. A pristinely Romantic spirit, Schumann, like Schubert and

Woyzeck's Buchner and maybe Bellini and Chopin, had a

relatively brief, disturbed and unhappy life. All of these early

nineteenth century Romantic geniuses worked best in small or

closed, often programmatic forms. Scenes from Goethe's Faust

were not composed as a musical unity - much less a larger dramatic

unity -but as separate, brief segments written in mostly backwards

order over ten or so years. Thus we had only Goethe's words to guide us through the evening,

with Book II being famously abstract and difficult, and here made

more so by Schumann's use of truncated and non-consecutive tracts.

For synthesis of word and music we had to rely on Faust,

Mephistopheles, Gretchen and various symbolic characters to bring

these scenes to life. Gretchen is not a large presence in

Schumann (or Goethe), and thus the small scale performance by

Daniela Bruera was adequate. Mephistopheles does loom large in

Schumann's scenes, and a huge, dynamic presence would have been

helpful in simulating a dramatic action. Michele Pertusi

delivered a Mephistopheles that would have been convincing in an

oratorio rendering of the work, but missed grounding the role on

the operatic stage. Faust himself, Markus Werba, began the

evening as too young and too green a Faustian presence, and soon

lost his voice besides so that an extra intermission was taken to

give time to organize cuts in the score, notably Faust's death

monologue. For the rest of the evening Mr. Werba made some

sounds, mouthed most lines particularly in the higher tessitura -

therefore at the more dramatic points – and yet beautifully

enacted several sublime moments.

Robert Schumann was not an opera composer, though we learn from

the Teatro Regio's program booklet that he did compose one opera,

Genoveva, an experimental, recitative-less work that has

been presented in recent times by Palermo's Teatro Massimo.

Strange, this Italian preoccupation with Schumann.

So Schumann is unknown operatic territory, as is Goethe's Faust

Book II (1832). We do know a bit of Book I (1806) from Berlioz

(1846), Gounod (1859) and Boito (1868) though it is an accepted

sacrilege to associate these derivative masterpieces with the real

Goethe Faust. But Schumann's Scenes from Goethe's Faust

are simply that, the actual Goethe verses; the first three briefer

scenes are from Book I, the final four scenes, longer and more

involved come from Book II, meaning that the larger part of the

work is uncharted territory for audiences and for this critic as

well, probably among most others.

Yet for us in the theater there was a beginning, middle and end to

the performance, though we struggled to make it so, having only

producer Hugo de Ana's staging to help us. Mr. de Ana worked with

basic solutions, in the first scene personalizing Goethe's Faust

to become Schumann himself with Clara Schumann seated at a grand

piano as Gretchen, though this conceit was then abandoned. The

following scenes were either blatantly straightforward as for

example the realistic cathedral where Gretchen prays, or else

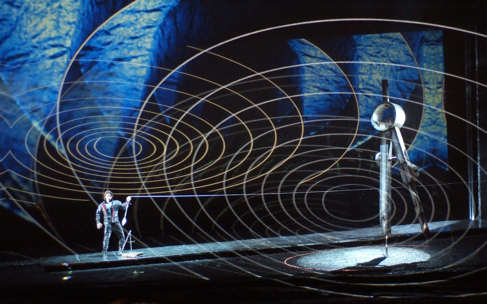

symbolic like the huge projected compass (drafting tool) for the

palace where Faust envisions his grandiose earthly projects.

Faust expiates his remorse for Gretchen's death in a fantastical,

silver lighted forest (silver is the word used by Goethe) with the

elves and spirits of the large chorus dressed in large, light

reflecting, silver robes. The final scene representing celestial

perfection was made by the large chorus alternately holding or

sitting on small, lighted boxes, while a cherubim encased in

larger plastic box descended from above from time to time.

These were made sublime in part because there were no words. The

Schumann orchestra sang out the Faustian condition instead with

Faust himself physically embodying these inspired musical

utterances - particularly at his death, in his embrace of the

physical world, and ultimately at his apotheosis. The Schumann

score in the hands of conductor Donato Renzetti was in heartfelt

coincidence with these Faustian postures.

Hugo de Ana is a brilliant designer, and an obviously

extraordinarily expensive one. Schumann's overture was accompanied

by a stunning vision of heavenly bodies flying through the solar

system. His use of projections and lasers through out the evening

was spectacular, with massive physical scenery intermixed as well,

in an onslaught of visual images that overwhelmed the simplicity

and integrity of Schumann's music. Mr. de Ana's costuming was

confusing too, combining abstracted flapper era evening dress with

costumes appropriate to timeless legends, many of the costumes

with fantastical flourishes that would wow in a Las Vegas show but

seemed vulgar in the Teatro Regio.

Schumann's musical impetus is ephemeral, even momentary, and his

sound is uniquely transparent and curiously unobtrusive while

remaining gloriously lyrical. Mr. de Ana's shapes are volumetric

and huge, and always beautiful. His concepts are basic,

straightforward and literal. But slice it how you want,

Schumann's Scenes from Goethe's Faust remains an oratorio

not an opera.

Pictures © Teatro Regio di Parma

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page