Other Links

Editorial Board

- Editor - Bill Kenny

- Founder - Len Mullenger

Google Site Search

SEEN

AND HEARD INTERNATIONAL CONCERT REVIEW

Moniuszko, Offenbach, Franck:

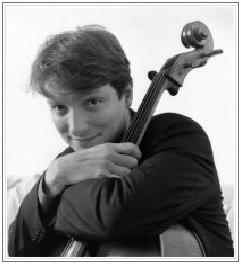

Jérôme Pernoo (cello),

Bavarian State Orchestra, Marc Minkowski (conductor), National

Theater, Munich 21.4.2008 (JFL)

Marc Minkowski is not a conductor known for conventionalism, whether

it be his interpretations or the repertoire itself. Guest-conducting

the Bavarian State Orchestra (the opera’s orchestra) in its Fifth

Akademiekonzert of the 2007/2008 season, he underlined that

perception by opening with Stanislaw Moniuszko’s Halka

Overture, a lovely little, bubbly curtain raiser that whets the

appetite for more music of Poland’s largely forgotten ‘national

composer’. Then followed the whacky, oversized

cello concerto

of Jacques Offenbach.

The sounds convey one thing above all: someone who knew the cello,

its abilities and possible abuses, intimately wrote this to have all

the fun imaginable with the instrument. Jérôme Pernoo, the young

French cellist that Minkowski brought with him, succeeded in

conveying this impression not only about the composer (said to have

been the Franz Liszt of the cello), but also about himself.

Stanisław Moniuszko: ”Halka” Overture

Jacques Offenbach:

Cello Concerto ”Grand concerto militaire”

César Franck: Symphony in d-minor

Stanisław Moniuszko

Yes – Jacques Offenbach wrote a cello concerto, and it’s not just

the one-movement Concerto Militaire, seldom enough played in

its own right and actually the first movement of the Grand

Concerto. The concerto has been reconstructed from fragments

that have floated about since the 1940s, but the completion could

not take place until 2006 when Jean-Christophe Keck, the publisher

of the critical, complete Offenbach edition found Offenbach’s

handwritten score in the Library of Congress and an archive in

Cologne. Now we know that the Concerto rondo is the finale of

this Grand Concerto, and its nickname “militaire” makes more

sense than it did when it was applied to the rather un-martial

stand-alone first movement. That first movement opens gently, softly

with timpani touches. It quickly swells, hitting a sporting and gay

stride until the cello enters – solo – with a double-stop studded

opening statement and then giving away to something altogether more

hysterical.

Jérôme Pernoo

Given the sometimes ridiculous challenges that this work presents –

high register double stop-sequences especially – it wasn’t by means

of technical perfection that Pernoo achieved this, but through

buoyant joy, verve, and plenty spunk. Listening to him play this

concerto, one could not help but expect it to take cellists’

repertoires and concert halls by storm… despite its considerable

length (45 minutes) and the downright silly technical demands it

places on the soloist.

Generous and decidedly knowing applause after the first movement was

the just reward and about as high a praise a soloist can get

nowadays, when applauding between movements is usually scoffed upon

as boorish and ignorant. Indeed, my seat neighbors glared into the

program notes where three movements were indicated and muttered that

this errant applause was “not at all in accord with concert

etiquette”. Indeed it was not (as wasn’t the concerto itself) – and

thanks be for that.

Very little military attitude in the highly lyrical,

flute-twittering and cheery second movement Andante – the

only entirely new music in this work. The duo between cello

and first violin (Markus Wolf) must surely be among the most

immediately and widely pleasing moments in cello concerto history.

Between the artillery and infantry shots from the third movement’s

percussion ranks, the cello and the strings put down such an

infectious romp that a sort of Beer-hall joviality threatened to

erupt in the dignified surroundings of the Munich opera house.

Admittedly that might be over-interpreting the smiles and rhythmic

twitching of the audience – young and old in equal measure – but

does not

overstate the character of the music. The back and forth between

those percussion batteries and the soloist had – in the good sense –

moments of absolute hilarity, concluding with a particularly harsh

passage that leaves the cello – metaphorically – limping off stage. Chock

full of lust for composing and playing the cello, unbridled fantasy,

like an excited puppy blissfully running about the orchestral stage:

this concerto cares not about convention, only entertainment. Had a

composer of lesser stature than Offenbach attempted this, the result

might have been an embarrassing disaster. As it is, there are more

moments in this work that made me smile broadly than I can count. A

feat not possible had it not been for the willing and sympathetic

support from the Staatsorchester.

Pernoo clearly found his vehicle here – a thankful one for everyone,

though I suspect that for all its entertainment value also one

vulnerable to overexposure. Until then, though, there was and is no

reason not to join in the trampling, hollering, and incessant

applause that was the response at this performance. The Barcarolle

was promptly encored, with Pernoo as soloist extraordinaire.

The second half was given to César Franck’s Symphony in d-minor,

which made for interesting comparison with the performance of

Riccardo Muti.

Now conducting with a regular baton, not the thick, piano-lacquered

black wand from his collection of historical ‘instruments’,

Minkowski got a much more French sound than Muti from this utterly

un-French symphony which is organ-like as Bruckner’s symphonies are,

chromatically akin to Wagner-Liszt-Reger, and structurally more like

Brahms than anything else. Minkowski – throughout the evening – also

elicited an excellent, unusually deep and sonorous sound from the

orchestra which played with musicality and humanity that it never

reaches under Kent Nagano, whose cold musical

photorealism

is more akin to a Ron Kleeman or Ralph Goings paining than

organically unfolding, musical joy.

Jens F. Laurson

Back

to Top

Cumulative Index Page