S & H International Concert Review

Sospeso Xponential: Moving Pictures and Illustrated Songs, The Ensemble Sospeso, The Angel Orensanz Foundation Center for the Arts, New York City November 11, 2003 (BH)

"In Absentia" -- Film by The Brothers Quay, music by Karlheinz Stockhausen

Helmut Lachenmann: Pression

Kirk Noreen: The Magician

Wolfgang Rihm: Am Horizont

Magnus Lindberg: Ablauf

György Ligeti: L’Escalier du Diable

"The Kiss" -- Film by Joshua Cody and Paul Bozymowski, music by Joshua Cody

Harrison Birtwistle: La Plage

John Cage: 4’33"

Joshua Cody: Adytum

Jeff Sugg, production designer

Miranda Hardy, lighting designer

Shu, technical designer

Robert Weiss, live videographer

Jon Okabayashi, production consultant

Kevin McMahon, sound designer

John Francis, set designer

Joshua Cody and Kirk Noreen, production

How do we listen to music? What do we visualize while we are doing it? How might we listen to music? These and a flood of other questions were raised in a fascinating, often riveting experiment devised by the Ensemble Sospeso, marking five years of provocative concerts in New York. Titled Moving Pictures and Illustrated Songs, the evening was envisioned as a continuous piece in ten parts, with each leading immediately into the next. The only separations between them were brief texts projected onscreen above the performers, who were alternately hidden from view and revealed by screens.

One could hardly imagine a more startling beginning than anything by the Quay Brothers, two brilliant animators originally from Philadelphia who now work in London. Their claustrophobic visions inhabit a world of gaseous, decrepit landscapes, often populated by dolls (or parts of them), armies of rolling nails or screws, or as in this case, extreme close-ups of the hands of a woman repeatedly trying to write a letter, while battalions of pencil tips shuttle across the floor. Coupled with the haunting Stockhausen score, this short film conjures up a grayish, straitjacketed nightmare, and is dedicated to a woman identified only as "E.H.," who lived and wrote to her husband from an asylum.

Then came Helmut Lachenmann’s Pression, a spare collection of scratches and other tiny sounds, acutely delivered by Chris Finckel, while videographer Robert Weiss captured, processed and then projected his movements onscreen, all in real time. This was followed immediately by Noreen’s The Magician, an eerie work that began with sensuous, quiet breathing by the peerless accordionist William Schimmel. I liked the Rihm, also beautifully played, and then came Lindberg’s striking Ablauf with a clarinet line punctuated by shocking, almost painful bass drum outbursts by two percussionists, here positioned upstairs in the balconies. Clarinetist Anthony Burr and percussionists David Shively and Thomas Kolor only heightened the work’s inherent primal energy.

Ligeti’s L’Escalier du Diable comes from his second book of Etudes (1985), and is horrifyingly intricate, with torrents of scales in seeming perpetual motion. Just when the pianist reaches the summit of the keyboard, the entire mad, exciting process seems to begin all over again. Despite the increasing popularity of these studies -- and this is one of the most difficult -- few pianists can tackle them with the steely concentration and force shown here by Stephen Gosling.

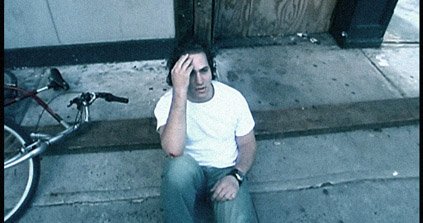

Joshua Cody and Paul Bozymowski’s film, The Kiss, begins with an account of structural problems in the Citicorp building in the 1970’s, but eventually reveals itself as a discreet meditation on September 11, 2001. The film’s many haunting scenes, particularly of aircraft silently crossing the screen and seeming to disappear into buildings, seem to prey on our still-fresh underlying anxieties. Just when I thought I might have reached the limit of 9/11 reflections, I found myself musing on that day of loss from yet one more angle.

The Birtwistle, fine as it was and anchored by some elegantly precise singing by Lucy Shelton, seemed somehow overwhelmed by the time it appeared, although the performance itself was excellent. Conductor Matthew Cody led a witty version of the Cage, including a "Rondo" section that had several in the audience tittering, and also led the final piece, Joshua Cody’s imaginative Adytum for chamber ensemble, including taped sounds of audience applause and laughter.

It must be said that the evening was just too long, despite the bold, insightful structure and high quality of the performances. For an array of intense, challenging modernist works lasting almost two-and-a-half hours with no intermission, there were problems of focus and pacing that weren’t entirely solved. I would whittle the (admittedly impressive) list of pieces down to six or eight, if only to ensure that an audience is better able to assimilate what they are seeing and hearing. By the time the last film began, I was already anticipating the end of the evening -- not because of the film itself, but because my ability to focus was waning. Nevertheless, it is clear that the group is thinking in ways that few groups do, and exploring how music, visual arts and words can be combined in ways that reinvent, re-examine and comment on each other.

The Orensanz Center, an unusual addition to the New York concert scene in recent years, proved to be a close-to-ideal venue. Originally built as a synagogue, its craggy, neo-Gothic, slightly dilapidated interior has been left intact, with the upper echelons lit with blue neon and ultraviolet light.

Bruce Hodges

(The writer is on the board of directors of the Ensemble Sospeso. Still photographs from "The Kiss" can be seen at http://www.sospeso.com/.)

Return to:

Return to: