S & H International Concert Review

Philadelphia Orchestra at Carnegie Hall: Balinese Gamelan Performance, Messiaen: Turangalîla Symphony The Philadelphia Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach, Carnegie Hall, New York City, October 7, 2003 (BH)

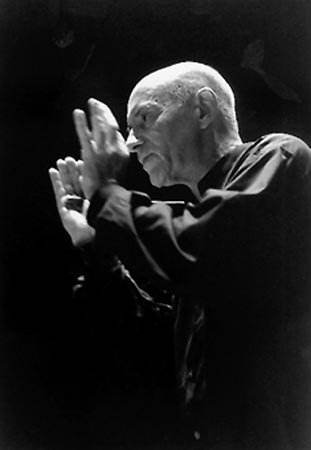

Christoph Eschenbach, Music Director and Conductor

Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Piano

Jean Laurendeau, Ondes Martinot

Gamelan Semara Santi of Swarthmore College

I Nyoman Suadin and Thomas Whitman, Co-directors

Sumptuously attired in navy blue tunics and blood-orange pants, the Gamelan Semara Santi of Swarthmore College opened last night’s Philadelphia Orchestra concert with two vivid examples of Balinese music, an inspired prelude to a towering Messiaen Turangalîla Symphony after intermission. After being blessed with sprinklings of flower petals and water, the ensemble presented two pieces, Sekar Ginotan (c. 1920’s) by I Wayan Lotring (according to Thomas Whitman’s clear program notes, arguably the most influential composer in 20th-century Bali), and Garuda Anglayang (1997), an almost jazzy workout for the ensemble by its co-director, I Nyoman Suadin. Both works were equally intriguing, with the 20-odd players making gorgeous sounds on a lovely array of instruments built by I Wayne Baratha in Bali. But one could savor just watching the musicians at work, striking the brass keys of the intricate, red-and-gold jegogan, calung and ugal using elegant small metal hammers or small gourd-shaped mallets. It all looked pretty regal on Carnegie’s white stage.These cascades of shimmering, sometimes thundering microtones made a really splendid first half of an imaginative evening dreamed up by Christoph Eschenbach in his first full season as the orchestra’s new conductor. In a short curtain speech before the ensemble began, he felt that the gamelan would "help your ears slide into Messiaen’s music," and his instincts were absolutely right.

Then came the Messiaen, one of the hugest animals around. I am familiar with two recordings: Myung-Whun Chung and the Bastille Opera Orchestra, and Riccardo Chailly with the Concertgebouw. (Either can be heartily recommended.) In this instance, the gigantic orchestra included eight percussionists lined up against the back wall, all dashing about madly from bells, to wood blocks, to glockenspiel, to marimba, to maracas, to sets of chimes. It was almost exhausting watching this busy team of surgeons dissecting Messiaen’s fascinating instructions and creating delectable sonorities in the process. At its peaks, with the entire orchestra synchronized and working nonstop, the effect felt like some sort of vast factory floor.

The work itself incorporates so many divergent influences it is difficult to describe them all. One friend felt that the score invoked Respighi, an appropriate reference given Messiaen’s extreme colors, not to mention his tendency to deploy the sonic equivalent of small explosive devices. (Having just recently become acquainted with conductor Lorin Maazel’s dazzling Cleveland Orchestra recording of the Pines of Rome and Feste Romane, it would be interesting to hear what he would do with a score like this.) What is always evident is the composer’s enormous appetite for sonic sources of all kinds, whether from Debussy, Bali, India or from nature’s bird songs. You name it -- it’s in there.

The score is just too complex to report on all of its ten sections, but in the rapturous fifth, "Joy of the Blood of the Stars," the Philadelphia players really showed why they are among the world’s top ensembles, their virtuosity and fervor matching the composer’s. Using Jean-Yves Thibaudet on piano might seem like luxury casting, but the reality is that in places the piece sounds almost like a piano concerto. Just when it has been assimilated into the ocean of percussion, it is yanked out for a dazzling solo turn. Thibaudet (who also appears on Chailly’s recording) seemed completely fearless, despite some moments when even his page-turner seemed a bit nonplused with the score’s brutal demands.

The excellent Jean Laurendeau worked his magic with the ondes martenot, a curious electronic successor to the theremin that produces a vibrant, slightly swooping sound. (Think of the film The Day the Earth Stood Still.) Its exotic color sometimes seemed to sail almost mischievously above the densely packed orchestra, before diving down again to be all but lost in the almost constantly flowing sonic rivers of Messiaen’s vision.

I am happy to report that the audience loved this program, summoning the conductor, Thibaudet and Laurendeau back for four curtain calls. If this is a sample of what’s bubbling up in Eschenbach’s head, Philadelphia is in for a wild, exhilarating ride.

Bruce Hodges

See also Prof Robin Mitchell-Boyask’s review of Christoph Eschenbach’s Messiaen concert in Philadelphia (ed).

Christoph Eschenbach’s website is here

Return to:

Return to: