S & H Opera Review

Berlioz, The Trojans, Part 1: The Capture of Troy, ENO, 5th February 2003 (MA)

No bones about it: Stewart Laing’s designs for The Capture of Troy are farcical, juvenile, and entirely counter-productive. From the opening, where a piece of aircraft fuselage lies on a bare stage, before a plain black backdrop, I was uneasy: this was going to be a streamlined account. But Laing and director Richard Jones between them turned out to have mischief in mind: their efforts crippled the music at every turn. The chorus emerges in T-shirts, slacks, shorts, sweaters and sneakers – bang goes the epic dignity of Berlioz’s Troy.

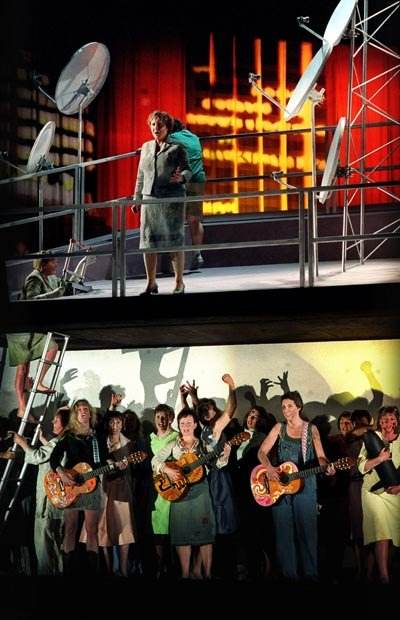

Susan Bickley sang Cassandra with stately fervour, but Jones had her dressed as a frumpy, middle-class bank manager. Every time her despair mounts at the deafness of the Trojans to her imprecations, she is seized by an exaggerated trembling, looking for all the world like a terminally malarial Anne Widdecombe. But the hour-long First Act rides entirely on her shoulders: undermine the credulity of the character and the whole edifice crumbles. Andromache comes onstage as Jackie Kennedy, remembering Hector as JFK via a projection on a screen dropped down from above. The Trojan women in Act II, scene 2, go to their deaths as guitar-strumming Greenham Common sistahs. Berlioz’s libretto has them leap to their deaths. Here they carry a number of bombs onto the roof and another screen drops down, stage-wide, with crudely painted bits of masonry and wood being blasted asunder. It’s the final idiotic gesture in a production which systematically ruins one of opera’s grandest scores.

Paul Daniel’s direction couldn’t do much with the music to overcome such self-indulgent banality. His musicians gave him a workmanlike reading which had a long way to go to match the rhythmic crispness of Sir Colin Davis’ account on his LSO Live recording – now the template against which performances of The Trojans will be measured for some time to come. The ENO chorus, though, under threat of shrinkage from the management, sang with a passion that suggested they were out to make their point as plain as possible: cut our numbers and you won’t get a sound like this from us again.

But even that thrilling noise couldn’t save the day. Berlioz was a radical and the last person to object to experiment – he lived his entire life taking risks. But he gambled in pursuit of higher truths. This production has set its sights much lower: it’s crass, devoid of insight and feeling, boorish, lamentably unimaginative. People like Sellars and Miller link operatic mythology with contemporary conditions because the tensions of the second illuminate the tensions of the first. Here we had only fey allusion: unless the appearance of the evening’s first black face as the leader of the triumphant Greeks is supposed to hold symbolic value, Jones/Laing made no attempt at all to inform what we were seeing with conflicts we might remember. After the huge wooden horse had been dragged across the stage at the end of Act I, I watched its arse disappearing into the wings – and there went the perfect metaphor for this misbegotten enterprise.

Martin Anderson

Further performances: 12, 15, 21, 25, 27 February. The Trojans, Part 2: The Trojans at Carthage opens on 8 May.

Laurie Lewis

English National Opera, New Production / The Trojans Part I: The Capture of

Troy

Return to:

Return to: