Following upon a disastrous

Trovatore

ENO and its Music Director, Paul Daniel, have redeemed themselves with the

latest revival of their 1997 Falstaff - pure gold and a wonderful

night of music theatre. What a marvellous tonic and encouragement for today's

senior citizens is this fabulous achievement of Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901),

completed when he was close on 80, first given in 1893, and the next year

in its proper location, London and starring a late developer who now commands

the world's operatic stages. And how right that it opened this year at London's

Coliseum on a hot May night in the burgeoning high Spring. Even though the

story is set in winter, the finale celebrates young marriage and the promise

of new life, with snowflakes giving way to a shower of confetti or petals.

The plot is simple but its telling by Shakespeare and Boito not simplistic. The thoughtfully illustrated programme book has excerpts from correspondence between composer and librettist, and amongst several essays, one by Germaine Greer stresses how essentially English is the social scene explored by Shakespeare - his merry wives enjoyed a freedom at which foreign observers marvelled. The perennial sport of adultery, never far from theatrical entertainment through the centuries, is transposed and here is more about humiliation of self seeking sexual predators (who are really after money more than love) and the curing of jealous husbands.

Andrew Shore [PICT Bill

Rafferty], whose famed Falstaff has been admired with Opera

North, WNO & at Glyndebourne, and will be seen across the Atlantic at

Santa Fe, dominates the action with his well-ripened assumption of the loveable

rogue, with a myriad of telling details of characterisation developed at

ENO under the direction of Matthew Warchus first, now Steven Stead. The

rumbustious start is a little worrying, with Stuart Kale's outraged Dr Caius

bawling out imprecations against unrestrained assertive orchestral outbursts

unleashed by Paul Daniel, but a fair balance is soon achieved and mostly

maintained. The cast respect piano markings and get across most of

the words of Amanda Holden's excellent translation, fully vindicating ENO's

dedication to opera in the vernacular - no English speakers should regret

the lack of Boito's original Italian.

Andrew Shore [PICT Bill

Rafferty], whose famed Falstaff has been admired with Opera

North, WNO & at Glyndebourne, and will be seen across the Atlantic at

Santa Fe, dominates the action with his well-ripened assumption of the loveable

rogue, with a myriad of telling details of characterisation developed at

ENO under the direction of Matthew Warchus first, now Steven Stead. The

rumbustious start is a little worrying, with Stuart Kale's outraged Dr Caius

bawling out imprecations against unrestrained assertive orchestral outbursts

unleashed by Paul Daniel, but a fair balance is soon achieved and mostly

maintained. The cast respect piano markings and get across most of

the words of Amanda Holden's excellent translation, fully vindicating ENO's

dedication to opera in the vernacular - no English speakers should regret

the lack of Boito's original Italian.

Paul Daniel guides the orchestra, keeps in close rapport with his singers, and moulds the moods of the moment, finding the right rhythms and rubato to accommodate precious respites from the hurly-burly, like Falstaff's reminiscences of his supposedly distinguished youth and prime - he is not troubled by any false modesty or lack of self esteem - and the fleeting, shared moments together snatched by the young lovers (Susan Gritton and Toby Spence - delicious).

Andrew Shore's repertoire of body language encompasses, without exaggeration, every aspect of this gullible hero, without whom, as he reminds us there could be no downfalls, no fun and no story to celebrate. Nothing is overdone in this production. He is corpulent, but dignified in his carriage, and it is far from incredible that there might be women to fancy such a fine figure of a man - his dressing up for dual assignations too does not go over the top into the ridiculous (as is expected, say, for a Malvolio). He is still nimble on his feet, even if troubled by a bit of arthritis in his knees, which spoils some of his grander gestures. And the singing is mellifluous, rock steady, and perfectly enunciated. Shore's assumption of one of the greatest comic roles in opera is one to savour in the memory for its countless details.

But Falstaff is a team opera, and this one is strong, well sung and acutely characterised in depth. His side kicks Richard Roberts (with the red nose) and trigger-happy Clive Bayley keep the fun going and are good, if quarrelsome, companions for Falstaff, however shamelessly they exploit him - you feel they will all be together again after the show is over.

Of the plotting pranksters, Ford's wife Alice, Yvonne Kenny, steals the show whenever she is on stage. She is clearly brighter than her husband, Ashley Holland, who plays his part in her artifice (and sings well in the opera) but is so readily persuaded of her infidelity, as operatic men tend to be. She moves with style and authority in her gorgeous costumes, always elegant, her voice soaring in melody and precise in negotiating rapid conspiratorial patter, supported by Alice Coote as Meg, her friend and foil, who winces because she is condemned to continue to wear green for her last Act disguise. They are abetted skilfully by Rebecca de Pont Davies (Mistress Quickly) who finds a convincing manner and rich lower register for her easy double entrapments of the big man. The children are effective tormentors in Windsor Forest (a very clever transformation) and Steve Kieve (illusions!) has a marvellous moment with them in the trompe-l'œil setting outside the Garter Inn, peopling the middle distance with ladies who turn out to be dressed-up little children (the programme has several illustrations of perspective tricks in 17C. theatre).

[PICT Setting for a Comedy (1640)]

The vivid colours of the women's costumes, which the singers surely enjoy wearing in this production, look as if they had been lifted out of Italian Renaissance paintings, whereas the men's garb seems to belong more to a motley crew of English folk. In his finery, Falstaff has the air of a grandee à la van Dyck

The Italianate sets (Laura Hopkins) abound with inventive detail, heads popping out of small windows, snow scenes glimpsed through an open door, a sailing boat in 'the Thames' through a window, an icicle under a drain pipe next to where Falstaff sits recovering from his drenching, and much else to bring a smile. The atmospheric lighting (originally Peter Mumford, revived by Jenny Cane) creates shadow plays on the walls and seems to allude metaphorically t o the darker side of this work. The large shadows seem like the looming shadows of old age, failing powers and failing attractiveness. Like the shadows cast by light, Falstaff is cast aside by women (life). Reality and illusion have one source and have become inseparable. The resort to cruel mockery is the cure applied to remedy this unhealthy state.

For our reassurance, Falstaff resurfaces, not only from the Thames like some primal, if somewhat dented force, but also like some unbending, unruly element from the second deceitful onslaught, to live for another day, his gusto a counterpoint to bourgeois decency. The co-production with Opera North and New Israeli Opera is apparently intended for much smaller opera houses than the Coliseum, and the compact compression of the action concentrates focus and invites the creation of an urgent DVD. Although we have not seen it before, so cannot be certain, this Falstaff is unlikely to have ever been in better health than now. It would make a wonderful companion to the small home stage (screen) presentation of the other Falstaff, which is one of our most treasured DVDs (Salieri Falstaff ).

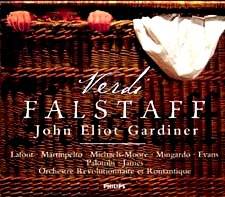

The new studio CD recording of John Eliot Gardiner's cleaned up version,

with his Orchestre Revolutionaire et Romantique playing original

instruments of the time, should be in the collection of anyone who cares

seriously about this miraculous Verdi comedy

(Phillips

462 603-2PH2). I enjoyed best its last Act in the forest,

with its magical make belief and the delicious little aria of the Queen of

the Fairies; the elaborate charade was not hard to visualise. Earlier, I

missed the rough and tumble of the stage action; though the libretto with

translations is provided, you try following the words when everyone sings

and plays with breathless haste all at once for pages on end - I found myself

marvelling at the task of writing down all those notes at the composer's

time of life. You are kept on your toes savouring unfamiliar, pungent

instrumental tones and Gardiner's whole conception is swift and driving onwards,

with brazen fortissimos, and quicksilver precision to keep you as alert as

is he. But the cast is not, taken as a whole, to be compared with this one,

and if you want your merry wives in their native English, rush to catch this

revival at the Coliseum whilst there are still some seats, and urge ENO to

film it quickly.

Peter & Alexa Woolf

Further performances on 14, 17, 19, 22, 24 & 26 May (www.eno.org).

Return to:

Return to: