The Opéra de Paris is flexing its considerable muscles in June with the final two productions of its 2000-2001 season. Coming on June 27 is opening night of a new Manon with Renée Fleming and Marcello Giordiani. La Damnation de Faust, opening on the June 5, was a production that, until now, has only been seen at the Saito Kinen festival in Japan during the Opéra's visit in 1999. It is an unqualified success for the director Robert Lapage and another triumph for the conductor Seiji Ozawa.

Not an opera in the traditional sense, Berlioz finally chose to call it a

'dramatic legend,' it makes great demands on the orchestra and conductor,

who are at the centre of the action. These challenges were met magnificently

by an orchestra that reached new heights of eloquence. Already enjoying new

respect under the leadership of Music Director James Conlon, it played like

a virtuoso instrument for Ozawa. It was a performance of blazing brilliance,

with tight tempos and stirring energy. Sitting up high, I was able to see

the wild ovation given Ozawa at the end by the members of the orchestra.

It was a musical love affair and the sold-out audiences could only benefit.

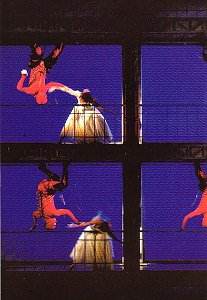

It also creates demands on the production team because of the long stretches of music interrupting the drama. In the 1960's, at the Palais Garnier, the Opéra had Maurice Bejart stage this work, with ballet as an integral part of action. Here they employed the very creative Canadian stage designer Robert Lapage. With designer Carl Fillion, he used the full forces of the team at the Bastille to create stunning visual images that were carefully calibrated to fit with the action and music. Treating the proscenium like a 16/9 format television screen, he divided it into grids to provide repeated images of often stunning impact. Employing dancers, climbing acrobats, extras and filmed images to fill the squares, the scenes fit well with the music and were, except for some merely decorative moments, a significant artistic achievement, as well as fine theatre. The size and complexity of this production, with its incumbent costs, might discourage companies less blessed with resources, both financial and technical.

Projecting images on screens in opera is not a new idea. I remember Frank Cosairo doing this in a production of A Village Romeo and Juliet at New York City Opera in the late 1970's. But the technology has developed since then. The video artists Bill Viola and Nam June Paik have made video images into high art and an important part of many contemporary art collections in major museums. The projected images are no longer washed out but crystalline and are capable of multiplication and manipulation. Here each grid has its own retractable screen so images can be projected on some grids, or in the case of the Part Three aria of Marguerite, a single image can occupy the vast Bastille stage. When Jennifer Larmore sings "D'amour, l'ardente flamme" the image behind her is of a giant fence of branches, filling the whole stage, gradually being consumed by outsized flames.

Larmore's singing was a bit of a disappointment. Obviously very talented, she sang very well but missed a level of interpretation that would make her a great Marguerite, much like a candidate in a voice competition: a finalist but not a prize winner. Last month at Théàtre du Châtelet, Grace Bumbry sang the same famous aria. It was a lesson to all young singers on how to make this aria the imposing musical statement that it is. José Van Dam was his usual impeccable self and sang Mephistophélés with grand menace. If you ever get a chance to hear this legend before he retires from the stage do not pass it up! On the night I attended, the tenor Giuseppi Sabbatini was indisposed and Keith Lewis sang Faust. Apparently reached while on vacation in Paris, Lewis was a classic last-minute replacement. Unfortunately, on this trip Mr. Lewis forgot to pack his top. In an otherwise credible performance, when he went high, the sounds were lamentable. The American baritone Clayton Brainerd sang a sturdy Brander.

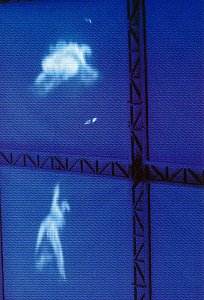

The production shared honors with the conductor this evening. The association

of the stage images with the music was innovative in opera production and

contributed much to an astonishing operatic event. During the musical interlude

'La

course

a l'Abime," for example, where Faust and Mephistophélés are

described in the text as galloping on black horses, Lapage uses eight repeated

images of running horses by the early photographer Muybridge. As these horses

gallop, in cadence with the music, shadow figures of Faust and the devil,

suspended on wires, mime the riding in each frame.

course

a l'Abime," for example, where Faust and Mephistophélés are

described in the text as galloping on black horses, Lapage uses eight repeated

images of running horses by the early photographer Muybridge. As these horses

gallop, in cadence with the music, shadow figures of Faust and the devil,

suspended on wires, mime the riding in each frame.

This new approach of combining the visual with the musical could be a part of the future of opera. Last December, at the world premiere of El Niño by John Adams at Paris' Théàtre du Châtelet, the audience saw singers with some stage action, and all coordinated with a film by Peter Sellars bringing the nativity story into contemporary East Los Angeles. Whether or not this is the course of opera production in the Twenty-first Century, this production, done with such skill and creative energy by Robert Lapage and his team, was one of most impressive theatrical experiences in my memory. It is not scheduled for the next season at Bastille but will certainly be reprised in the future. Make your reservations early.

Frank Cadenhead

Credits: Festival Saito Kinen 2000, photos M. Okubo

Return to:

Return to: