ENO's first new Don Giovanni since 1995 reverses the didacticism that good triumphs over evil - both literally and metaphysically: there is more cruelty in this intensely comic production than one would normally expect to see in a lifetime of comic opera-going. Yet, Mozart would probably have warmed to this production by the Barcelonan director Calixto Bieito as it does adopt the Mozartian critique of society touched on throughout the libretto -merely transporting it from the eighteenth century to the nineteen nineties. Its controversy does not lie in this 'updating' but in how Bieito eschews interaction between the characters and concentrates instead on a subliminal interaction between place and environment and, most of all, political satire. This production lays the blame for boorishness and infidelity clearly at the door of society. No character in this production (least of all Don Giovanni) emerges with any degree of sympathy - and even characters such as Donna Elvira have any humanity removed from them by Bieitos' insistence that they too are invariably looking up from the gutter. This is a Don in which all the participants are high on drugs and sex and corrupted by it. Look at this production as a two-week holiday on a tacky Spanish resort.

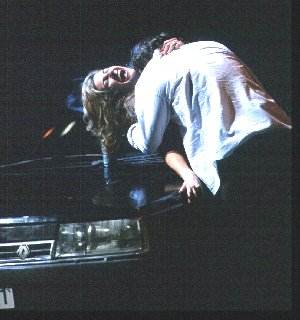

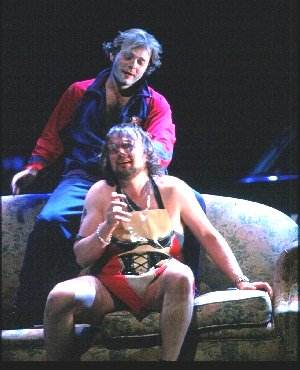

The production opens with Leporello (an excellent Nathan Berg, greasy haired and track-suited) emerging from a car driven on stage - while Don Giovanni and Donna Anna remain inside rocking the car from side to side with their energetic 'lovemaking'. Immediately the location is set, the first act's obsession with possessiveness and greed laid prostrate before us by a cast lusting in the rancour of an Ibizian piss-up. Bags play a big part in all this - amusingly so. Leporello's Adidas bag (which he is not without once throughout the entire first act) acts as a sort of mini-bar crammed full of lager cans - which both he and Don Giovanni guzzle laddishly throughout the drama. Donna Anna's bag is more discerning in design (Essex girl leather) but it is left to Donna Elvira (a memorably comic performance by Claire Weston), with her three shopping bags (albeit designer ones), to emphasise the tragedy of these characters' predicaments. Like a tired bag lady she carries these around as if they are the only memories from a once happy life and which now literally are the only possessions of her life. Has she been reduced to this by Don Giovanni's cruelty? As he humiliates her further by kicking them around stage like a football the answer becomes evident as she is stripped of any dignity. As Act II opens she is seen slumped across a table, drunk, as her humiliation comes full circle. Elvira is now a drinking, chocolate devouring figure seeking solace in anything other than the people around her. The brutality of the Commendatore's knifing (Tarantinoesque in its violence), Ottavio's semi-pornographic seduction of Donna Anna, Leporello's Act II humiliation (with sexual overtones of sadomasochism) and the voyeuristic filming of the wedding and party all seek to exploit the characters' inability to do anything about the human predicament. It certainly leaves a nasty aftertaste.

Indeed, the major problem with this production is the sheer weight of Bieito's vision which compels one to be less interested in the music than in the on-stage action. In being almost too clever for his own good Bieito relegates Mozart's score to a firm second place - almost as if this were in fact theatre rather than opera. As if to emphasise this the ensembles were often scrambled - diction drunkenly slurred. The Ball scene which concludes Act I here becomes a raucous party the effect being to totally undermine the balletic scoring. Don Ottavio's and Donna Anna's minuet is banished (and not just because she is inexplicably wheelchair bound) and the three stage orchestra's suggested in the libretto are no where to be seen. The synchronisation and rhythm which this scene usually suggests is removed - indeed, this party was a free-for-all that bordered on the orgiastic. Even where Mozart intended to establish an equanimity of balance and order Bieito feels free to establish disunity and chaos.

Film (or the suggestion of) haunts this production like the ghost of the Commendatore (who in the end is no ghost at all). The filming of the wedding and party scenes, with close ups of simulated sex, invokes the voyeurism of films such as Michael Powell's Peeping Tom, yet when the film-maker adopts a Thatcherite face mask it takes on more sinister suggestions of Big Brother watching them. It is not until later we realise exactly how perverse this camera work has been. The TV, which sits on stage at the opening of Act II, reminded me of Derek Jarman's Blue - if only because the screen remained Tory blue. When the screen actually changes from blue to the film that had been shot earlier the sense of prying and voyeurism really is brought full circle. Now we are the voyeurs. Yet, Leporello's torture, with his nipples and legs being tweaked and his binding, like a crucifixion, reminds clearly of the martyrdom of St Sebastiane. As Leporello crawls around the stage dressed like a Union Jacked armadillo one is reminded again of one of Jarman's starkest films, The Last of England. The iconography in this production is ultimately unsettling - so much is being said, often simultaneously, that a sense of suffocation settles in.

Perhaps more startling is Bieito's draconian wilfulness in rewriting the drama of the libretto. The Commendatore's reappearance is not as a statue at all -Don Giovanni instead sees him on the label of a bottle - no doubt from a mescaline-induced state of druggedness. When the Commendatore reappears he does so from the boot of the car (with the apt number plate C-TORE 1 one should have anticipated it) - and still very much alive. Don Giovanni merely kills him again. Rather than being dragged to hell and sinking into the flames, as the libretto suggests, the final septet is used as a scene to murder Don Giovanni. The way in which this is done, with each character getting revenge for being the subject of Don Giovanni's cruelty, indicated that Bieito must have seen Ruggero Deodato's House on the Edge of the Park. As in that film's climax, any sense that the character's can win back their humanity is dissolved by their desire for vengeance in the most violent of terms.

Despite the formidable problems with this intellectualised staging (i.e. what is really going on?) the singers attack their roles with power and commitment. Garry Magee's Don Giovanni is well sung and his cherubic features mask a malevolent streak in his acting (which whilst not quite as convincing as Nathan Berg's is still memorable). Claire Rutter is a rather magnificent sounding Donna Anna and Phillip Ens a commanding Commendatore. Joseph Svensen conducts a fast paced performance (the opening overture was very fast indeed) although the playing (even from where I was sat in the stalls) lacked passion and drama and was toneless.

This production has been greeted with almost universal hostility. It deserves little of it. Calixto Bieito's direction is clever (perhaps too clever) but it at least challenges one's preconceptions, which is something you cannot say about many opera productions today.

Marc Bridle

Further performances of Don Giovanni are on June 16, 20, 26, 29 and July 2 & 6.

Return to:

Return to: