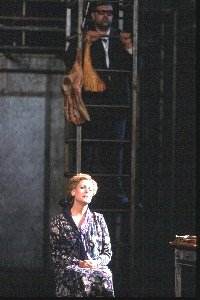

So infrequently has Lady Macbeth of Mtsesnk been performed in Britain one could be forgiven for thinking that opera houses agree with the 1936 Pravda editorial that the opera is 'a muddle instead of music'. ENO, however, in their fabulous revival of their 1987 award-winning production by David Poutney and Stefanos Lazaridis, clearly see things differently - that, yes, this is one of the most startling of all twentieth century operas.

Lazaridis' set is striking. The centrepiece is a giant revolving structure

which acts as house, cold store and abattoir - as well as the Siberian road

on which the prisoners march at the opera's conclusion. The severity of the

scaffolding, the blanched rawness of the carcasses hanging from meat hooks

or splayed on side tables and the simplicity of the furnishings all go someway

to portraying the hardship of Soviet women as labourers in a predominantly

poverty-drenched world. The overriding expression is of squalor and brutality

- something that Poutney irrevocably associates with the barely suppressed

sexual anger with bubbles under the surface of this production. The rape

of the cook may not be explicitly shown (as it is in Peter Weigl's film of

the opera) yet her balletic writhing needs no explicit demonstration of rape

for the shock of the scene to become effective. Sergei's sadistic beating

- again not graphically shown - is imagistic in its beauty as Boris rhythmically

hits a bloodied piece of meat and his torturers smear Sergei's back in red

paint. Yet, whilst Poutney is restrained at depicting this theatre of cruelty

in graphic intensity there is no doubt that a sexual miasma hovers like a

lingering stench over proceedings.

How ironic,

therefore, that when Katerina and Sergei have sex (to the wonderful sound

of glissandi trombones) that her bed is covered in flowers. The Pre-Raphaelite

suggestion of a Holman Hunt is astonishingly vivid yet out of place. It almost

compels us to believe that Katerina is not a guiltless murderess but a victim

of oppression.

How ironic,

therefore, that when Katerina and Sergei have sex (to the wonderful sound

of glissandi trombones) that her bed is covered in flowers. The Pre-Raphaelite

suggestion of a Holman Hunt is astonishingly vivid yet out of place. It almost

compels us to believe that Katerina is not a guiltless murderess but a victim

of oppression.

Where this production is really breathtaking is in its use of light. Occasionally characters were spotlit - Sergei, for example, before he descends to meet Katerina - but mostly (and largely in the final two acts) light was used in a gripping and universal way. As Katerina and Sergei are arrested the police literally break down the doors. What remained created the appearance of war-torn buildings as shards of light shone through the desolation. Where previously only carcasses had hung from the rafters we now had contorted bodies, darkened and lit from behind, creating silhouettes of human carnage. On a back drop behind the stage the faces of prisoners, tattooed only with the anonymity of a number, looked forward like a tapestry. Nowhere else in the opera did Poutney's direction seem so cinematic, so redolent of an Eisenstein as the mood shifted from Technicolor to an extraordinary sepia and black. Yet, Poutney had evidently taken the shifting colours of the score on board - the garish orchestration of the Police chorus was shrouded on stage in Soviet red and the death of Boris was masked in a velvety darkness.

Beyond the tragedy of this opera it is easy to forget the comic elements. Both the priest's song over the dying body of Boris and the drunken peasant were moments of high comedy - as was the Policemen's chorus (once memorably described as something out of the Keystone Cops). A nice touch was the inclusion of three witches gibbering away on the wing's of the stage. When they mixed the cocktail of poisoned mushrooms Katerina feeds Boris it irresistibly reminded us of the very opening of Shakespeare's Macbeth with the witches huddled over the cauldron.

Much of the strength of Lady Macbeth comes from its astonishing score. Written roughly at the same time as Shostakovich's Fourth Symphony it has many of that score's features: a hybrid of shattering dissonance and wild rhythms. The orchestra played it magnificently and were nowhere better than in the great passacaglia - with striking cellos and basses like blackest anthracite in their tone. Brass, both from the pit and from the on-stage band were exemplary in their delivery. There was also some memorable woodwind playing. Mark Wigglesworth, making his ENO debut, conducted a thrilling account of the score - raw when it needed it to be but profoundly moving also, particularly in the final scene. Vivian Tierney, singing Katerina, gave an all-embracing performance which was as astonishing for the expressiveness of her voice as it was for the beauty of her phrasing. She was elemental in the upper reaches of the register and sang with tremendous passion throughout. Pavlo Hunka was a great Boris, rich of tone and Robert Brubaker, singing Sergei, has a heroic tenor's voice ideal for the part and not the least bit hectoring in tone. The remainder of the cast and the chorus showed a commitment all too often lacking in opera productions undertaken on this scale.

|

|

This lavish production is a triumph for ENO. See it now before it disappears again for another 10 years.

Marc Bridle

Further performances are on June 19, 22, 25, 28 & 30 and 3 & 5 July. The performance on 3 July will be recorded by BBC Radio 3 for broadcast on 7 July.

Return to:

Return to: