By no means on the tourist festival circuit, Geneva is a delightful centre for a short stay in early spring. The 10th Archipel Festival of contemporary music with associated events ran from 21 March to 1 April came to our notice from the Gaudeamus Foundation's indispensable bi-annual information book, and during our visit for the first week of Archipel we attended eight of its events.

Geneva is a compact city, close to the French border, traversed by two rivers

and overlooked by hills and mountains. During the daytime there is plenty

to do, whatever your preferences, be it exploring the old town, visiting

some twenty four and more museums and galleries, or just shopping and eating

- all at favourable prices for British visitors.

There is a series of parks along the lakeside, one of them a fine Botanical

Garden, and a spectacular fountain the other side of Lac Leman. This year

we enjoyed a special visual bonus of some excitement. Unusually persistent

rain had caused flooding in Europe alike as in England. The clear water of

the Rhone in Geneva was swollen and joined in a dramatic confluence near

the city centre by the Arve, another fast-flowing river which had practically

obliterated its sidewalks, its water opaque from carrying material down from

the French mountains.

An uncommon musical experience was assured by opening a major international festival with a most unusual concert of keyboard music, provocatively titled Piano Là. The proceedings started with Wolfang Heisig from Dresden, exponent of the pianola, a machine which requires far more skill and energy to operate than you might imagine. He gave a selection of the Studies for Mechanical Piano laboriously punched out in piano rolls by Conlon Nancarrow, which indulge in such complexity of rhythm and tempi when composed as to defy any possibility of human realisation on a normal piano. They are joyful pieces, which gain from the live spectacle of the multitude of keys playing with apparent virtuosity all by themselves, whilst the player treads the pedals (like those of a harmonium); Heisig's knees pumped up and down, working the pneumatic mechanism like a maniac to keep up with the swathes of notes. The back of the Hupfeld-Meisterspiel-Phonola has 'fingers' which engage with the keys of a normal piano, on this occasion an upright Bechstein, giving a more lively feeling, though with less clarity, than is to be heard on the Wergo CD transfers.

Between Heisig's two Nancarrow 'sets', the ubiquitous Ian Pace had flown in to Switzerland for a fleeting overnight visit (his first) to give the Swiss premiere of the four Études of Dusapin, which had been doubly-premiered in Strasbourg, shared there among three pianists. They benefited immeasurably by the perfect acoustics of the fairly small Salle Ernest-Ansermet of Radio Geneva and initial doubts about the studies were swept away. The two dreamy, romantics ones created a spell with a haze of harmonics, set in the context of the other two fast, finger-knotting examples, very much in the Ligeti vein of complexity, demanding endurance and the concentration of a brain split into two to instruct the scarcely sufficient ten fingers. Throughout the evening the focus was upon the inner life of the piano and its resonances elicited from the keys (mercifully, without any of the composers represented requiring the pianists to stand up and grope around the instrument's innards, at risk to their backs). This limitation actually highlighted the intrinsic modernity of the musical languages being explored.

Sciarrino's Sonata No.5 was a playful scherzando study, an intimate jeu d'esprit which initially played around with small scrunching finger clusters, expanding them into a large structure. Never had I heard the notorious chordal repetitions of Stockhausen's Klavierstuck IX so exquisitely individuated, its spell-binding effect owing much to the ideal acoustics, with nothing extraneous to be heard apart from the very faintest imaginable ticking of the seconds from an electronic clock. The total silence of the rapt audience, hanging upon every sound, and the subtle, discreet 'support' (not to be confused with 'amplification') engineered by André Richard. This made for a unique experience, worth the journey to catch up with Ian Pace once more, so soon after his marathon concerts in London. Markus Hinterhäuser (piano) with André Richard presented Nono's ...sofferte onde serena... (1974), composed for Maurizio Pollini and his 'unique sense of sonority'. This has an elaborate part for tape. The whole conception grew from personal sufferings of composer and dedicatee and the sounds of the bells of Venice, using a 'spectral analysis' of the potential sonorities of the piano. A rich brew and an auspicious start to the festival. After a long day travelling from London, we did not stay for a late night session of piano improvisation, nor did I hear later in the week Markus Hinterhäuser's recital in which he introduced to Geneva all Galina Ustvolskaya's piano sonatas, revelatory by all accounts for those new to them; see my recent review of all the recordings of Ustvolskaya's piano music, including Hinterhäuser's (col legno wwe 20019).

A second evening in the Salle Ernest-Ansermet was given over to

Anches libres, memorably opened

by Pascal Contet (concert accordion) with a series of inventive solos

which demonstrated his devotion to expanding the versatility of the

bayan, an increasingly popular instrument in Europe (see the Gaudeamus

Competition in Rotterdam) into new and experimental music of our time.

Particularly notable was Trois rèves for amplified accordion

with tape, a substantial and rewarding work in three linked movements by

André Serre-Milan. Contet ended with His Master's Voice,

an essay into canine psychology by Camille Roy, complete with

exactly the right dog, Paulo, who behaved impeccably pattering around in

the Radio Geneva studio.

One strand of the festival (as in previous years) was improvisation, but its potential for delight was poorly represented in the only example that we heard. Rudiger Carl from Hamburg displayed only limited imagination or skill on piano-accordion, mouth organ (and clarinet) served only to remind me of one of S&H's correspondents who shares my scepticism of that movement in contemporary music, and wrote recently that 'the best improvisers are light-speed composers who can filter and alter and reject unnecessary material and still leave room for instinct and inspiration'. (See also S&H April Editorial.)

The evening was wound up with a selection of traditional music on Argentine's national instrument, the bandonéon (internationally popularised by Astor Piazzola) given by César Stroscio, an original member of the "mythic' Cuarteto Cedron. Stroscio had established the first Chair of Bandonéon in Europe, and showed himself a virtuoso and master of expressive rubato stretched to its limits. The music's relaxed and sentimental mood was just right towards midnight, but perhaps might better have been moved to the convivial bar outside the auditorium?

There was a second opportunity to experience the phonola in the spectacularly converted Batiment Force Motore, a vast 19C building straddling the Rhone, built to control the water levels of Geneva's Lac Leman. Now it contains a large concert hall and a vast foyer with the original machinery on display, was a spectacular site for a solo concert Phonola in my head by Wolfgang Heisig, who told me that his instrument is a very close cousin of the English pianola, whose influence had spread into Europe; he had enjoyed comparing notes with the leading British exponent of mechanical pianos, Rex Lawson, when they shared an appearance in Munich.

For us, Heisig's programme turned out to be another Nancarrow appreciation event. Two more of his Studies were as winning as ever, and Heisig's own Heisivertonongen was an engrossing realisation of the rhythms and articulation of a spoken text-music piece, replicating its patterns. But the rest descended into the cult of minimalism which has held such sway in UK & USA (destructively, many feel) spilling over onto the concert which followed. Gavin Bryars deployed his usual standard harmonies and repetitive arpeggios in Out of Zaleski's Gazebo, one of those works (originally for two pianos) in which the title and programme notes promise far more than is actually delivered, and the nadir was reached with Heisig's risking injury to his knees in his machine-gun rendition of Tom Johnson's interminable The Chord Catalogue. That is no less than an unsmiling permutation of every one (leaving aside micro-tones) of the 8178 chords possible within one octave, a pointless exercise in a concert situation - though we do now enjoy listening to some of J.S.Bach's theoretical constructions which were never designed for public performance, so the experiment in Archipel was possibly justifiable, and Johnson should not be dismissed on account of one aberration? However, I do not propose to review the CD nor supply the complete listing to MusicWeb!

Nor did things greatly improve in Desert Music, the evening's main concert, which brought in a very large audience (of Reich enthusiasts, so I surmise). The piano (with its keyboard relations, the main focus of the festival this year) was represented by one of those works in which composers without forceful musical identities are apt to forsake the keyboard and resort to the entrails inside. In this case local pianist/composer Rainer Boesch, founder of Geneva's Studio Espaces, was abetted by two assistants responsible for 'informatique and spatialisation' respectively in the second part of his ...ferner Schnee, which alludes to the peak of Mount Fuji. Despite its complex genesis in collaboration with Nicolas Sordet, this was, for us, instantly forgettable music, but Steve Reich ensured that could never be said of his grandiose, insistently loud and ultimately pulverising The Desert Music of 1982-94, given by amplified orchestral and choral forces from Basse-Normandie & Caen, each musician provided with his own personal microphone. Though described as one of a group of works in which Reich explored Hebraic cantillation, there was no attempt at illuminating word-setting, and we were left to ponder the limitations of his settings of "shall we think or listen - - it is a principle of music to repeat and repeat again - - ". This is music which de-humanises orchestral players and choral singers, and becomes an endurance test of concentration to avoid becoming conspicuous by miscounting and making mistakes; conductor Dominique Debart ensured there was no let-up in the deployment of collective energy, and the audience response indicated that our reaction was not the general one.

The evening had however been worth attending for the first item in that concert. Dominique Debart directed a new Double Quintet in four movements for winds and percussion (Percussions-Klaviers from Lyon and wind players from Caen) by Bruno Giner (b.1960), a French composer and music writer who has studied widely (at IRCAM and with de Pablo and Ferneyhough amongst others) and has a sure and original ear for subtle combinations of instrumental timbres. Tam-tams were used integrally, not just for climaxes, and there were hard, dry sounds which brought to mind ritualistic music of Japan. A new name to explore, and one of the reasons for travelling to festivals abroad.

Our last evening at the Alhambra, a large former cinema, brought a full house for Paroles d'Utipie, a tough evening devoted to Stockhausen and his devotees. This is impressive for a small city whose population numbers no more than Greenwich, the London borough where we live, and is a credit to the organising team. The programme put an emphasis on live electronic manipulation, the sounds swirling around us in the darkened auditorium for Emmanuel Nune's darkly scored Nachtmusik 1 for lower strings and winds and Luigi Nono's uncompromising Risonanze erranti (1986), with its original dedicatee Susanne Otto and five hard hitting percussionists, bass tuba and ear-splitting piccolo (I must check whether Nono or Ustvolskaya was first to think of the latter unlikely pairing?). Do readers find that the fashion for extinguishing light, which made it impossible to follow the complex texts and commentaries provided, really aids concentration as, presumably, intended? It diminished pleasure in Niccolo Castiglioni's Cantus planus (1990-91), twenty-four tiny epigrams, fastidiously set in a manner which brought Webern to mind. Their simplicity and transparency, however, clearly pose intonation problems for the duetting sopranos Maacha Deubner and Luisa Castellani, who needed to resort constantly to checking with their tuning forks. This concert was an elaborate production involving conductors Jurjen Hempel & André Richard and the renowned Ensemble Contrechamps, with Les Percussions du CIP and a group of presiding sound technicians from IRCAM and SWR's experimental studio, including composer/conductor/engineer André Richard, who had served Ian Pace so well previously and contrived that Stockhausen's pioneering Gesang der Junglinge came up fresh as ever after nearly half a century and stole the show!

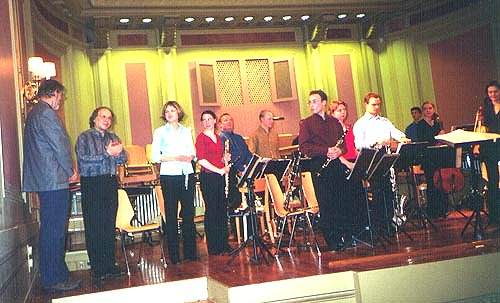

Followers of Seen&Heard will not be at all surprised that we found far greater satisfaction in a daunting programme of music impeccably prepared by music students; in London the best concerts are often to be heard in music colleges. Participation of young musicians has always been fundamental in Archipel programming. The Ensemble Contemporain of the Geneva Conservatoire was joined this year by the musicians of La Schola di Alto Perfectionamente from Saluzzo, Italy, for a richly scored new sextet by Bruno Mantovani (one of the prizewinners who had made a mark at Stuttgart's Eclat).and a selection of scores by Lachenmann (featured composer at the Huddersfield Festival 2000) under the direction of Jean-Jaques Balet.

Helmut Lachenmann (b.1935) [above] figures amongst the most remarkable figures of our time and represents perhaps the most radical of the influential approaches towards music towards the end of the last century, questioning and challenging all assumptions and preconceptions of the western concert scene, going further even than did Schönberg and Boulez when they tried to dictate the direction music should take in the future. Lachenmann dreams of a kind of music which should be expressive of curiosity, ready to question everything. He has created a new musical alphabet, which systematically explores all the different 'noises' which instruments can create. His music is geared to make us discover new regions not yet part of our perceptions or our routine hearing.

Especially with his piano works Helmut Lachenmann has managed to transform the sound heritage of that most familiar of instruments, with continual questioning of our perceptions of resonances, forms and the 'shadows of tradition'. (This it was which prompted Jean Prevost to feature all the keyboard instruments as a unifying theme in Archipel 2001.) For Lachenmann, nothing is sacrosanct and every element is meat for analysis and recreation. He writes music without making concessions to the normally overwhelming assumptions about the 'true' character of familiar instrumemnts and that a 'beautiful sound' is a paramount goal. He analyses rather than prescribes. During our week in Geneva, he took composition and orchestration classes at the Conservatoire, and will have taught the students to listen to, and respect, the many sounds which they would have previously ignored, or assiduously worked to eliminate during their long instrumental studies. The preparation of the extremely complex Movement (-vor der Erstarrung) composed (and de-composed!) for the Parisian Ensemble InterContemporain (1982-84) will have given them infinite food for thought about where music has come from and might go. Lachenmann told me that this 'sportive experiment' with the young musicians had given him great satisfaction.

The second week had more Lachenmann (a repeat by his pianist wife and colleagues of the concert given at Huddersfield) and features George Crumb with UK's The Smith Quartet (Django Bates in their concert being the only British composer represented in the festival other than Bryars!), together with discussions, film and installations. Finally, Heinz Holliger directed a complete performance of his Scardinelli Cycle.

The whole complex exercise is masterminded by one of those visionaries who give the best Festivals their own distinct individuality. Jean Prévost, who was involved from the early days, has been Artistic Director since 1995 and he has contrived to combine featured composers in attendance (Kagel last year, Toshio Hosokawa 1999, Pierre Henry, Michael Jarrel & Georges Aphergis 1998, Berio & Gubaidulina 1997) with the development of thematic connections between separate events. His success is reflected in the enthusiasm of the audiences, which come from a cross section of society and in a healthy mix of age groups. Generous sponsorship makes possible inexpensive tickets, with various additional reductions available. Reasonably priced refreshments are available at each auditorium, all within easy walking distance.

A unique feature is the attractive presentation of background information, Prevost supplying most of the texts succinctly and in a manner to provoke thought - usually no pictures, but extremely elegant graphisme (Eva Rittmeyer). The covers of their (free) programmes and the Archipel 'brochure', which takes the form of a handy pocket-sized booklet of detachable cards, carry a wealth of associations; we found these more enticing than many a usual glossy presentation. Everything combined to make the whole experience a pleasure and Archipel 2002 will be well worth checking out (www.archipel.org).

Peter Grahame Woolf

All the concerts of Archipel 2001 were recorded by Radio Suisse Romande Espace 2, which carries a regular 3½ hours Music of Today slot on Sundays at 22.30 (21.30 UK time), and will be included in those transmittions between 15 April and 1 July (details from www.espace2.ch), giving the possibility for Swiss visitors to the festival, and those new music enthusiasts abroad with satellite radio receivers, to record for future home listening rare and esoteric music of minority interest.

This arrangement, which cannot have been costly to set up, should commend itself to BBC R3 - how about inaugurating it for the Huddersfield Festival next November?

Peter & Alexa Woolf

Return to:

Return to: