ENO's huge auditorium has been transformed into a building site. Scaffolding connects the stage and the auditorium. A semi-circular walkway extends across the front of the dress circle. Long ladders create vertical access. Dustsheets cover the boxes near the stage; another hangs over a giant mirror frame up front. Life size, long nosed masked Venetian carnival figures, high up on the scaffolding surrounding the proscenium arch, intimate that it is unlikely that actual builders will be clambering all over these structures!

The surprise at finding a mundane work scene literally inserting itself into the space and aura of a hollowed cultural venue created a mental jolt. These transformations were designed by Stefanos Lazaridis whose work for the Royal Opera was recently admired by Seen and Heard (Martinu Greek Passion May 2000) and they relate to renovation of the building being undertaken. We were nearly persuaded that they had deliberately installed old, worn seats in the Circle, eventually realising that we had not taken in the parlous condition of those same seats which we had become accustomed to over the years! So Lazaridis has certainly made people look and think!

This setting is in place for the ambitious overview of 400 years of Italian opera now in progress at ENO. It will be interesting to see to what aesthetic, practical as well as metaphorical uses these structures will be put for works from Monteverdi to Dallapiccola.

However, they immediately rendered visual, made visible, that art is always work in progress, and that transformation is the life blood for maintaining a living tradition. The scaffolding is also a metaphorical framework, standing for opera as an art form holding together intellectual and emotional knowledges, as well as social and cultural values. In a less abstract vein, the scaffolding, especially the walkway, created a direct link between the performers and the audience. It broke down the separation to some extent and brought the action closer to many seat holders.

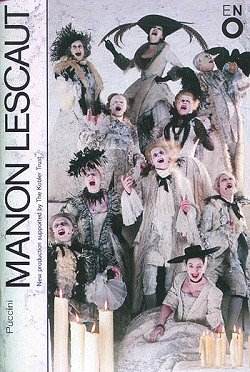

The chorus, which performed from the raised walkway and paraded like ghoulish ghosts dressed in unearthly stiff starched black and white 18th century style costumes, created the perhaps most memorable visual aspect of this production. They were deployed as onlookers, more or less detached from the action on the stage below and, thereby, acted as a kind of extension of the audience. The circular line thus created, connecting the audience with the performers, created a sense of coherence in an opera which gave Puccini a lot of trouble and in its final form has conspicuous narrative non-sequiturs and gaps in the story-telling.

Manon Lescaut was first performed in Turin in 1893. The story of a woman's descent from virtue to degradation and eventual death, familiar fare for 19th century imaginations, is based on a novel Histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut (1731) by Abbé Antoine-Francois Prevost (1697-1763), a French priest in the Benedictine Order, who abandoned the order and lived for several years in England and Holland.

It is set in the second half of the 18th century in France and America. The libretto had been worked on by seven different writers. That might have undermined a narrative fluidity, but the fact that Puccini produced four disparate dramatic worlds within this opera points to something more fundamental at work. A breakdown of linear surface narratives was in the air at the time and Puccini may have been in tune with this intellectual ferment. His music shows great stylistic diversity and complexity, especially in the first act, which must have been bewildering to anyone seeing it for the first time without prior homework.

However, there is one serious problem, which this eagerly awaited production pointed up. Any meaningful work of art is about communication. Opera depends on the interaction between musical, verbal and visual texts to transmit meaning. The visual and purely musical elements were of a high standard, but the most basic access to intelligibility through the explicit verbal content was made difficult. From where we were sitting in the front dress circle it might as well have been sung in Chinese! Some 80-90% of the text was aurally undecipherable, and would have benefited greatly from surtitles (c.p. Billy Budd given at Covent Garden later in the week with exemplary diction and great clarity, yet the English surtitles provided for this English opera were still much appreciated). As far as the S&H team was concerned, the effort to produce a new translation of Manon Lescaut seemed to have been sadly wasted. It is perhaps particularly important to provide surtitles for a work which does not have narrative continuity?

The Swedish soprano, Nina Stemme, a contender for the Cardiff Singer

of the Year competition some years

back, made her auspicious ENO debut as Manon Lescaut with David

Kempster as her dubious brother, who fixed her up with the rich old Geronte

(Mark Richardson). She was partnered strongly by Martin Thompson

who belted out his part, to cope with the difficulties presented by the Coliseum

and this setting, agilely climbing up ladders in the scaffolding, whilst

Manon scaled Lazaridis's golden spiral staircase to be captured at the top.

The translation of the student Edmondo into a grotesque master of ceremonies

(John Graham-Hall) was one of the less successful aspects of this

directorial rethinking by Keith Warner.

back, made her auspicious ENO debut as Manon Lescaut with David

Kempster as her dubious brother, who fixed her up with the rich old Geronte

(Mark Richardson). She was partnered strongly by Martin Thompson

who belted out his part, to cope with the difficulties presented by the Coliseum

and this setting, agilely climbing up ladders in the scaffolding, whilst

Manon scaled Lazaridis's golden spiral staircase to be captured at the top.

The translation of the student Edmondo into a grotesque master of ceremonies

(John Graham-Hall) was one of the less successful aspects of this

directorial rethinking by Keith Warner.

Paul Daniel welded together almost seamlessly the intricate textures of this problematic early Puccini opera with searing conviction, and the orchestra's playing for him was gripping; it is that which stays most in the mind's ear.

Alexa & Peter Woolf

Return to:

Return to: