************************************************************** EDITOR’s RECOMMENDATION June 2003 **************************************************************

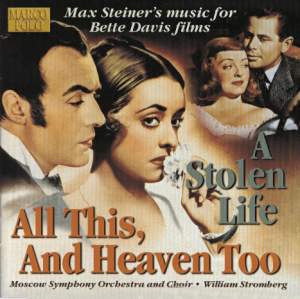

All This And Heaven Too and A Stolen Life

Music for Bette Davis films by Max Steiner

Score restorations by John Morgan

Moscow Symphony Orchestra & Choir conducted by William Stromberg

Available On: Marco Polo 8.225218

Running Time: 71:08

Crotchet

A shorter suite from Max Steiner’s All This And Heaven Too and the Main Title music from A Stolen Life were recorded by Charles Gerhardt conducting the crack National Philharmonic Orchestra, in his ground-breaking Classical Film Scores Series back in the 1970s, and released on an album with the virtually the same title ‘Classic Film Scores for Bette Davis’ RCA Victor GD80183. But now we can enjoy much more of the music of both films, especially that from A Stolen Life.

Some of Max Steiner’s best music was written for Bette Davis vehicles and she in turn appreciated its worth and developed a close working relationship with Warner’s leading composer. Max used to appreciate the fact that his romantically dramatic music was featured more strongly in Davis films to underline the strong emotional elements of the stories, whereas his more masculine, action material was often lost under sound effects.

John Morgan’s restorations provide 45 minutes of All This And Heaven Too score whereas Gerhardt’s suite spanned less than 8, but included beautifully played excerpts, with nicely romantic and tasteful rubati and portamenti: Main Title (a more musically satisfying performance than that on the new Marco Polo recording); Henriette and the Children; Love Scene; Finale and End Cast.

Concentrating now on the new recording, once past the slightly over-enthusiastic rendering of the Main Title the Moscow players sparkle. The score of All This And Heaven Too is dominated by a lovely theme that underlines the sweet, compassionate and stoical nature of Henriette Deluzy-Desportes (Bette Davis) the governess of the many children of the Duc de Choiseul-Praslin (Charles Boyer). Steiner’s score very cleverly evokes her caring relationship with the children, motherly, playful and consolatory. In contrast there is tradition and dignity behind the Duc’s music, and sour distorted material for his spoilt, difficult and unreasonably obsessively jealous wife whose madness at length provokes the Duc to murder and suicide (see the short article on the true background of All This And Heaven Too appended to this review).

Restrained music – reminiscent of that of the 18th Century, the Age of Elegance – informs the non-consummated love that grows between Henriette and the charming, understanding Duc. One of the most impressive tracks (and one on which John Morgan has done such a fine job working on such slim reference material) is the eerie, stormy of ‘All Hallows Eve’ with the female voices of the Moscow Choir. The same cue also contains a realistic evocation of the excitement and fairground fun of ‘The Carousel’ as seen through the children’s eyes. The score also contains some delightful cues that, without resort to mickey-mousing are very descriptive of scenes like ‘Carriage Ride’. The recording features one charming piece of source music – Gluck’s Overture to Armida - heard here in full and used for a scene at an opera house.

A Stolen Life (1946) was a story about twins (Davis in a dual role) – one good, the other evil (a popular theme of films of that era). The setting is the coastal region of New England and consequently much of Max Steiner’s music has a nautical flavour. The magnificent Main Theme (again slightly over-emphatically performed) is strongly dramatic and bracing – you can sense the tang of the sea and the strength of the two protagonists. As if to underline the mood a hornpipe follows that cleverly turns feminine, into Barcarolle, a beautiful waltz theme to illustrate the fun-loving, outgoing nature of Kate and then there is a hint of a slinky allure for Pat the other sister. There is some "oily" material for the unsympathetic Dane Clark character and suitably tender romantic music for the romance between Kate and the put-upon husband of evil sister Pat played by Glenn Ford. Interestingly Steiner reprises his moody fog music from King Kong for the sea storm sequences when Pat dies and the good Kate assumes her identity – a stolen life.

Two of Steiner’s most memorable scores beautifully and enthusiastically performed

Highly recommended

Ian Lace

41/2

[ Note: Charles Gerhardt’s Classic Film Scores for Bette Davis (RCA Victor GD80183) recording is recommended as a cornerstone film music repertoire choice. It comprises music from: Now, Voyager; Dark Victory; A Stolen Life; The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex; Mr Skeffington; In This Our Life; All About Eve; Jezebel; Beyond the Forest; Juarez; The Letter and All This And Heaven Too. ]

All this and Heaven Too -

A Mendelssohn’s Link to Murder, Suicide and the Downfall of a French King

This month Marco Polo releases a new recording of Max Steiner’s superior score for the classic Warner Bros. "woman’s film" of 1940, All This And Heaven Too, based on the best-selling novel by Rachel Field. The film, based on a true story, cast Bette Davis, somewhat against type as the caring, passive Henriette Deluzy-Desportes governess to the many children of the French Duc de Praslin. There is a link between the Mendelssohn family and this story –

The ‘founder’ of the Mendelssohn dynasty, Moses Mendelssohn was born in poverty in 1729, in the Jewish ghetto of Dessau. Small and humpbacked, he walked, at the age of 14, the eighty miles to Berlin where by dint of hard work in the silk business and diligent study he rose to become the most celebrated Jew in 500 years. He found fame as a leading philosopher and litterateur. He wrote Phaedon a philosophical tract after Socrates, but with Moses’s own thoughts in favour of immortality. It became the best-selling book of its day. Moses also set forces in motion which, although he did not intend them that way, led to a modernisation of Jewish religious practises.

Moses’ son Joseph later aided by Abraham, the composer Felix Mendelssohn’s father, were to found the prosperous Mendelssohn and Company bank that remained in existence until Hitler extinguished it in the late 1930s. Moses’ daughters were in the forefront of the women’s liberation movement of their day. One daughter, Dorothea Mendelssohn whose Berlin salons were a magnet for artists, scandalised Europe with her writings and amours. She left her dull businessman husband, Simon Veit, for the more intellectually stimulating and passionate Frederick Schlegel.

Another daughter, Henrietta, was equally independent-minded and adventurous. She shied away from men all her life. Her only interest in them was intellectual. She was no beauty. She settled in Paris and opened a school for the daughters of the wealthy but was ultimately persuaded to devote herself to becoming the governess of Fanny, the young daughter of one of Napoleon’s generals, Sebastiani, an extremely wealthy man. Sebastiani installed Henrietta in his household - a lavish house abutting the Elysee Palace. Henrietta converted to Catholicism and brought Fanny up strictly. Fanny, was lovely but empty-headed. Her marriage to the Duc de Choiseul-Praslin was disastrous. The relationship between Henrietta and her young ward was raised in the horrendous fate that overtook the Fanny. Fanny grew fat and flabby and madly jealous - especially when her husband began to seek solace with the young governess of their numerous children. In a rage he battered Fanny to death with a heavy brass candlestick. Two days later he swallowed arsenic. The murder-suicide caused a sensation. It contributed to the fall in 1848 of King Louis-Phillipe whose government was accused of having permitted Praslin, a member of the peerage, to commit suicide to escape trial and punishment. In one article that followed Henrietta Mendelssohn was practically accused of being a lesbian whose influence helped make Fanny Sebastiani incapable of having an emotionally stable marriage.

Ian Lace

Return to Index