QUADRILLE WITH A RAVEN

Memoirs By Humphrey Searle

Chapter 15: "TWO NEW CONTINENTS?"

Early in 1964 we received news from South Africa that Fiona's stepfather's heart trouble was getting worse and that he was not expected to live for more than a few months, and Fiona's mother asked if we could come out for a visit. It didn't seem possible at the time, as we simply hadn't got the money; but shortly afterwards I received an invitation from Stanford University, California, to be Composer in Residence for the academic year 1964-5. I had never been to America and knew practically nothing about American universities; fortunately my American friend and colleague Everett Helm was in London at the time and I was able to ask his advice. He strongly recommended me to go; I accepted the invitation and, on the strength of it, was able to raise an overdraft to pay for our South African trip.

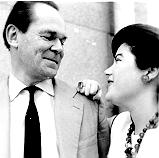

Humphrey and Fiona Searle, Johannesburg March 1964

We flew to Johannesburg in March; the journey took a long time, as we had to change planes in Luxembourg, and then stop off in Malta and several places in Africa. Eventually we arrived after about 28 hours. Fiona's friend, the well-known South African actress Marjorie Gordon, had found us a hotel in the suburb of Braamfontein. Next morning we awoke to teeming rain; Johannesburg is not the most beautiful city in the world, and that morning it looked exactly like Manchester to me. Fiona was not at all amused by this comparison since for years she had been extolling the marvellous climate of the Transvaal. I had not been too keen on visiting a country which practised apartheid, especially after having lived for a time in fascist Spain; but later the weather and my spirits improved and I found the rest of the trip interesting. Fiona's family all lived in Durban so for the next three months we alternated between Jo'burg, Durban and Cape Town, where I had been asked to give some lectures at the University by Erik Chisholm, the Scottish composer who had settled in South Africa; he had been the first person to stage Berlioz' "The Trojans” and “Beatrice and Benedict” in Britain before the war. Gideon Fagan, the former conductor of the BBC Northern Orchestra, was now musical director of the SABC in Johannesburg and offered me some broadcasts and, as Fiona was given some work in radio plays, we were able to recoup some of our expenses.

Meanwhile my publishers had arranged for the first stage performance of "The Photo of the Colonel” to take place in Frankfurt early in June, while the Musical Times in London had asked my old friend Malcolm Rayment to write an article about me for their June number and also invited me to write a short piece for unaccompanied chorus which was to be published in the same issue. A few months previously Fiona's cousin Irene Nicholson had given us her latest book "Firefly in the Night", which was described as "A Study of Ancient Mexican Poetry and Symbolism”. Irene was a remarkable woman who lived in Mexico City for 17 years as part-time correspondent of the London Times; during this period she wrote and translated several books about Mexican literature, art and even economics. I was particularly taken by her translation of pre-Columbian Mexican poetry, with their colourful imagery of song, birds and flowers and, for the Musical Times, I set one of her short poems “Song of the Birds”. I had also been asked to write a larger unaccompanied choral work for the Cheltenham Festival and for this I chose three more of these Nahua poems under the title of “Song of the Sun”. I worked on these pieces while we were in Johannesburg.

For the first part of our stay we moved between Jo'burg and Durban. I found Durban rather provincial; the weather was hot and humid, and bathing was restricted because of sharks. However the people were kind and pleasant, and there is some beautiful countryside outside the city. We visited Zululand and also spent an enjoyable few days in an hotel high up in the Drakensburg mountains where the scenery is breath-taking. Fiona was offered the leading part in a radio production of Ibsen's "When We Dead Awaken" and I made contact with the musical side of the SABC in Durban. In Jo'burg we usually stayed at the Federal Hotel opposite Broadcasting House; this is a small and rather shabby establishment whose bar was frequented by actors and most of the English-speaking journalists in the city. Here we heard some horrifying stories of the activities of the Broederbond, the Nationalist Afrikaaner secret society; and of course the signs of apartheid were everywhere. There were separate entrances in post offices for blacks and whites, separate benches in the parks, and so on. The city was full of blacks by day, mostly doing menial jobs, but they had to return to their black townships at night, often having to walk long distances. Surprisingly they always seemed cheerful and smiling while many of the whites looked nervous and apprehensive.

I met many of Fiona's friends from the time when she had worked in the theatre and radio in South Africa. These included Michael Silver, the head of the Commercial Radio Corporation, a good friend to this day, Siegfried Mynhardt, the actor who has been described as the Gielgud of South Africa - he has a beautiful speaking voice and had played the part of the poet Ishak in Basil Dean's production of Flecker's "Hassan" a few years earlier - and many other actors and actresses. They were an amusing and friendly crowd and we spent many cheerful evenings together. Occasionally we stayed with Mike and Ethel Silver at their splendid house in the Northern suburbs, where most well-off people live; the Southern suburbs are considered rather lower-class. Some of the actors lived in the centre of the city and we often visited Marjorie Gordon and her English husband Paul Vernon.

When the time came for us to go to Cape Town for my lectures, Fiona and I drove from Durban along the "Garden Route" together with her sister Sheila. We enjoyed the spectacular scenery although we often lost our way, and the 1100-mile trip took us four days. We had two mishaps en route; the first was a puncture. We were miles from anywhere, and discovered to our horror that there were no tools in the car. Sheila produced a nailfile, but it was hardly suitable for changing a wheel! We were in despair until we were rescued by a black gentleman in a large limousine, who had a splendid hydraulic jack. The second disaster occurred in the bush, not far from a place rather aptly called Wilderness; the fan-belt snapped and the water in the radiator boiled over. Here we were saved by a car-load of Cape Coloured (i.e half-caste) people, who gave us water and saw us on our way, refusing to accept any payment. None of the white people's cars which we tried to flag down would stop on either occasion.

Our last stop before Cape Town was at Somerset West, where Fiona had lived as a teenager. On retiring from India her parents had bought some land high up the Heldeberg Mountain, and her father had grown several types of fruit trees and had a house built there. Sadly, only weeks before the house was completed, he died; however for some years the family remained in Somerset West. It is a beautiful part of the country, not far from the Paarl Valley which produces excellent white wine, and the coastline east of Cape Town is as striking as that of the South of France, with the advantage that there were then no villas or hotels to spoil it.

Erik Chishoim welcomed me very warmly and did everything possible to make the lectures a success. Since Cape Town University was integrated I was able to talk to students of all colours on an equal footing. In Cape Town we also met the veteran pianist Dr. Elsie Hall, Australian-born but a resident of South Africa for many years. This formidable old lady was in her late eighties, but was still performing and was even then planning a European tour which included East Germany and other countries in the Eastern bloc. It was also interesting for me to be invited to dinner at the house of Fiona's old family doctor, an Afrikaaner whose wife spoke very little English, and to feel the atmosphere of an Afrikaans household - in this case a most cultured and enlightened one.

While visiting some of Fiona's friends at Gordon’s Bay, near Somerset West, I suddenly had an idea for a fifth symphony based on the life of Webern. Possibly the beauty of the mountains encircling the bay had led me to think of him, for he had been a great nature-lover and had lived and walked among the mountains of Austria in his youth. I'm afraid I was oblivious of the conversation going on around me but, by the end of the afternoon, I had worked out the complete plan of the work in my head.

We flew back to Europe at the end of May. As the aeroplane stopped at Luxembourg, we decided to stop off there and spend a few days in this quiet and pleasant city before going on to Frankfurt for the rehearsals of "The Photo of the Colonel". We explored the countryside of Luxembourg, and enjoyed the excellent food and wine, which was a contrast to the somewhat crude, if copious, fare which was typical of South African restaurants. Then we took the little train which travelled down the Moselle valley towards Frankfurt. Here rehearsals were well under way, with a good cast and quite an adequate production, although the singer who took the part of Berenger found it necessary to make several cuts in his role, especially in his final monologue. We used the electronic effects which we had made in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop for the London production, and the opera was quite a success with both public and critics.

We then returned to England, but not for long as I had been invited to attend a congress on modern opera in Hamburg, organized by the enterprising intendant Rolf Liebermann, who commissioned many operas and ballets from contemporary composers during his reign. In connection with the Congress he put on a fortnight of modern opera; among the operas I saw was "The Golden Ram" by Ernst Krenek, in which I was particularly impressed by the performance of the Finnish baritone Tom Krause in the part of Jason. He could not only sing but looked young and athletic and acted well. During the Congress Liebermann, whom I had known as a colleague and friend ever since my ISCM days, asked me to come and see him. He had heard of the success of "The Photo of the Colonel" at Frankfurt and now wanted to commission an opera from me. I naturally felt flattered. When he asked me what ideas I had, I mentioned that I had thought of trying to make Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra into an opera. Liebermann asked if I would be interested in writing an opera on King Lear; apparently Fischer-Dieskau had said that he would like to to play the part in an opera specially written for him. As 1964 was a Shakespeare Centenary year, a publisher had brought out a list of Shakespeare operas, mentioning that Benjamin Britten was at work on a Lear opera. As there was obviously no point in my doing the same, I told Liebermann that I would make enquiries on my return to England.

When we got back to London I found two offers of work waiting for me. Scherchen was arranging a series of programmes on Radio Lugano that winter which were to include all the Beethoven symphonies as well as a new work in each concert, and he wanted me to write a short piece for a Beethoven-size orchestra without trombones. And Lawrence Leonard, who had conducted several works of mine both at Morley College and with the Halle Orchestra, said he wanted to give the first performance of my fifth symphony in Manchester in October. Since the latter request was more urgent, I sat down and wrote the symphony fairly quickly, between June and September 1964.

I enquired from Britten's publishers whether he was really intending to write an opera on Lear and was told that he was. I also learnt that Samuel Barber was writing an opera on “Antony and Cleopatra"; then I suddenly got an idea - why not Hamlet? Practically all the action takes place on stage, apart from one or two scenes, such as Ophelia's description in Act 2 Scene 1 of her encounter with Hamlet in melancholy mood and the story of the switching of the letters during Hamlet's journey to England, both of which can be dramatised. The only narration which I retained unaltered was Gertrude's description of the death of Ophelia. At any rate I communicated my idea to Liebermann,and got a letter back which said: "Hamlet is marvellous. As marvellous as dangerous? Good luck!" And he recommended me to make Hamlet a baritone rather than a tenor, sasying "tenors are fat and stupid". As I wanted Tom Krause for the part I was glad to follow his suggestion. But I could not start work on Hamlet immediately. Apart from the piece for Scherchen, I was committed to translating and editing a selection of Berlioz' letters for one publisher and to translating Walter Kolneder's book on Webern's music for another, thus I could not get to grips with Hamlet until the following spring.

Edith Sitwell, whom I had not seen for some time, had heard that we were going to America, and asked us to come and see her. She had not been well for some time, and was lying in bed in the Hampstead house where she lived in her later years; her long pale fingers with their blood-red nails and massive rings were folded over the counterpane. She seemed pleased to see us, but the drugs prescribed by her doctor caused her mind to wander slightly, and she warned us not to let the American professors bully you . I never saw.her again as she died of a heart attack only a few months later, apparently after reading a stupid review of one of her books; usually her companions prevented such reviews from reaching her, but this time there had been a mistake. I was most glad to have known her; she was a distinguished poet and a great lady.

Before we sailed for America we gave a party to which Patrick and Olwen Wymark came. By a strange coincidence Olwen's parents were living near Stanford University where her father, Philip Buck, was Professor of Political Science. She wrote to them, and they offered to put us up in a shack at the bottom of their garden until we could find a place of our own. So at least we had somewhere we could go to on arrival. At the beginning of September Fiona received the news that her step-father had died suddenly; we were relieved that we had been able to visit her family in South Africa earlier that year.