QUADRILLE WITH A RAVEN

Memoirs By Humphrey Searle

Chapter 17: "LABYRINTH"

To coincide with the Covent Garden production of Hamlet, the Musical Times published an interview in which I answered questions put by Martin Kingsbury; they asked me to write a short choral piece which would be published as a supplement. Irene Nicholson had recently died, after a long illness bravely borne, and in her memory I set another of her translations of Mexican poems, this time not a Nahuati poem but an extract from the Spanish miracle play "The Divine Narcissus" by the 17th-century nun Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz: "Tell me, where is He my soul adores”, a very beautiful poem. At about the same time I was asked to write a song with French words for the Romanian singer Viorica Cortez, who was then singing Carmen at Covent Garden. I happened to have just come across Rimbaud's early poem Ophelie, which I didn't remember having read before; and so I chose that.

In the summer we went to Hamburg for the ISCM Festival which included "Hamlet". The music in the orchestral concerts was mostly rather dreary, and I didn't like Penderecki's opera "The Devils" at all, but I was interested to see Sandy Goehr's "Arden", which struck me as very successful. Sandy wasn't there, but his wife Audrey told me that the opera had been put on without any rehearsal, and the orchestral playing naturally suffered. That is the trouble with an opera house which has such an enormous repertoire as Hamburg had at that time; a later performance of "Arden" which I saw in London was far better musically, even if the staging was inferior. From Hamburg I went first to Rudesheim, where the Jungs gave a splendid party on the top of the medieval tower which forms part of their house, with wine from their own vineyard, and then to Karlsruhe, where I had a teaching position at the Rochschule fur Musik for some years.

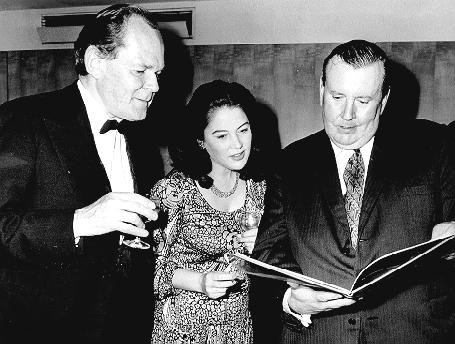

Buckingham Palace 1968

left to right

Mrs Searle, Humphrey Searle, Fiona Searle

I had been awarded a C.B.E. in 1968; I am not really interested in awards of this kind but Fiona and one or two friends persuaded me that the honour was as much for music and the arts as for me personally, so I did not refuse it. But about the same time I was given an honour which interested me much more; being elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Music was something of a bonus for someone who had had only ninemonths’ musical training in the whole of his life (there were only 125 such Fellows at that time).

Shortly after he got his CBE at a

Mansion House Midsummer Banquet in honour of the Arts.In August we went to Cyprus, our first visit to this beautiful and fascinating island. My friend Robin Russell, the former editor of the now defunct Times of Cyprus, gave us introductions to one member each of three different communities, Wally Kent, a British journalist, Charles Papadopolos, a Greek Cypriot member of the Cyprus Broadcasting Service, and Ali Fehmi, the Turkish Press Attache. This was of course years before the Turkish invasion of the north of the island and we were able to travel everywhere freely. We stayed first in the Ledra Hotel in Nicosia, then the haunt of all the journalists; later we hired a car and drove round much of the island. We visited Famagusta, but found it rather depressing, apart from the old town, though the ruins of Salamis to the north were most interesting. But the place we really loved was Kyrenia; we stayed at the Hesperides Hotel and got to know its proprietor Anastasy Kariolou, it was much nicer than the fashionable Dome Hotel opposite. In the early mornings, while everything was quiet and the atmosphere was unbelievably calm and peaceful in the beautiful harbour, we used to swim and water-ski. Through Wally Kent we met the Drs. Guthrie who had both retired from medical practice. John Guthrie, a big bearded man who strongly resembles James Robertson Justice, is an interesting composer, especially of songs, while his wife Vivian is a talented artist, using broken glass and other materials to produce remarkable results. They have a beautiful villa in the village of Bellapais in the mountains above Kyrenia; Bellapais, with its ruined medieval abbey, is a most attractive place and in its main square is the Tree of Idleness immortalised by Lawrence Durrell in "Bitter Lemons"; Durrell had a house in Bellapais at one time. This was the first of our several trips to Cyprus, and we have remained good friends of the Guthries to this day.

In October 1969, as part of British Trade Week in Vienna, the British Council organised a British Arts Week, sending out the Royal Ballet, the Royal Shakespeare Company and various musical ensembles, as well as a number of British composers, such as David Bedford, Harrison Birtwhistle, Peter Maxwell Davies and myself. Some modern British chamber works were performed including a quartet which I had written as long ago as 1948. The British Council also asked me to write a new piece for the Purcell Consort of Voices. I chose an amusing and rather bawdy poem about a young man, a girl and a pear tree from Faber's book of Medieval English Lyrics called "I have a new garden"; this seemed to go down well, but it would have been better if the glossary which I included in the score to explain the more obscure words had also been printed in the programme. I also took part in a discussion about Schoenberg, Berg and Webern and their influence on Biitish music.

From Vienna we went on to Budapest, where Szokolay's "Hamlet" was being performed; I felt I could now go with a clear conscience, as Hungarian troops had been withdrawn from Czechoslovakia. Apart from "Hamlet" we saw two interesting earlier Hungarian operas, Erkel's "Hunyadi Laszlo" and Kodaly's "Hary Janos"; the latter was great fun. I gave a talk on "Liszt in England" at the British Embassy which was attended by a large number of Hungarian musicians. The British Cultural Attache, Charles Hewer, and his Norwegian wife looked after us extremely well; one day they drove us to Esztergom to see the Romanesque basilica for the opening of which in 1855 Liszt had written his "Gran Mass”.

During the winter of 1969 I was engaged on a large work which Douglas Cleverdon had persuaded the BBC to commission from me, a "spoken oratorio" based on Blake's "Jerusalem"; (not the famous poem which Parry set but which I did make a setting of as an epilogue in my work) from the big prophetic book, "Milton", very much shortened of course. Most of the words are spoken over music by a cast of actors, although I set the actual poems to be sung. The prologue "Reader! lover of books! lover of heaven!" is an aria for tenor and orchestra, and so is "I saw a monk of Charlemaine"; the long poem which begins "The fields from Islington to Marybone" is set for chorus and orchestra, with a tenor solo in the middle, and the chorus sing the two final poems,"England! awake!" and "And did those feet". As usual, Douglas set recording and transmission dates which I had to keep to, and the whole work; which lasts about an hour, was written between December 1969 and February 1970. We recorded the vocal and orchestral music separately, and then the purely orchestral music by itself; the actors recorded their parts to the tape of the music, taking their cues from green lights. This is less satisfactory than the old method in which the orchestra sits in the studio and the cast take their cues from the conductor, but of course it is less expensive. We had a good cast including Carleton Hobbs, Denis Goacher, Margaret Wolfit and Ronald Dowd as the tenor soloist. Sir Geoffrey Keynes, perhaps the greatest authority on Blake, recorded a short talk explaining the somewhat obscure symbolism of the poem. It was a work I had always wanted to set, with its marvellous and exciting imagery, and its outspoken attack on materialism and war, and I was very glad to have the opportunity.

We went back to Cyprus in April 1970, staying again at the Hesperides Hotel in Kyrenia. Although the spring flowers made the island more beautiful than ever, it was really too early in the season; it was very windy, and the boat we had used the previous year had been smashed up by some youths. However, we visited the south part of the island with our friend Hazel Thurston, a tall and amusing Irish lady who had come to Cyprus to revise her guide book on the island. We shared a hair-raising drive in an ancient taxi from Nicosia to Limassol; the driver seemed hell-bent on exceeding 100 miles an hour. Fiona, in a desperate attempt to check the drivers speed, stuffed a cushion up her dress and drew the man's attention to her supposed pregnant condition. The driver grinned understandinglv and slowed down to a mere 90 miles an hour. At Limassol we were thankful to change taxis and we were driven to Paphos, where we saw the famous Roman mosaics, not all of which had yet been excavated. Then we hired a car and Fiona drove us across the Troodos mountains to Nicosia; Hazel wanted to visit a small but beautiful church hidden high up in the mountains, and the road to it was practically impassable, very stony and had a deep precipice on one side. We survived these somewhat frightening experiences!

Michael Bakewell, who was then Director of Plays at BBC Television, suggested that I might collaborate with Samuel Beckett on a new opera for television. As I was intending to go to Paris to meet the Crostens who were passing through that city on their way back from one of the European campuses which belonged to Stanford, I asked Barbara Bray, who I knew was a good friend of Beckett, if she could arrange an introduction to him. She sent me a message that he would like to meet me and he came round to our hotel, which was not far from his own apartment in Montparnasse. Both he and I are rather shy and it was left to Fiona to carry on an animated monologue; in the end Beckett asked us both to have dinner with him at his favourite restaurant in the area, and we had a most amusing evening. It turned out that he had no ideas for further theatrical work - he was writing only poems at the time - but he asked me if I could help his nephew Edward Beckett, who is a flute-player and a pupil of the famous master Rampal and who had recently graduated with honours from the Paris Conservatoire. I was able to put him in touch with the manager of the Sinfonia of London, my old friend Edward Walker and, although both he and his son are both flautists, he managed to get Edward Beckett some jobs as well; this was the beginning of his successful career in England and Ireland. I did eventually collaborate with Samuel Beckett; although a cousin of his, John Beckett, had written the music for most of Sam's radio plays, I was asked by the Audio-Visual Centre of London University to write music for both "Words and Music" and "Cascando". I gathered that the author was satisfied with the results.

When we were back in London, I was asked to write a new work for the Cheltenham Festival; it had to be for the 18th century combination of two oboes, two horns and strings. I decided on a set of variations and, when I had sketched out the work, I suddenly realised that the individual variations resembled the signs of the Zodiac in character, as described in astrological handbooks, such as "Capricorn, prudence, understanding". It made a musical form which reached its climax in Scorpio, "strong-willed, self-destructive" and ended quietly with Sagittarius, "reason, intellect". I used fairly spare textures for the strings and gave the horns some difficult parts with which, however, the young players of the Orchestra Nova coped very well; I stationed one oboe and one horn on each side of the strings, hoping to achieve a quasi-stereophonic effect, but the acoustics of Cheltenham Town Hall were not helpful.

The BBC revived "Oxus" at the Proms on 26 August, my 55th birthday. Gerald English was again the excellent soloist this time singing the part from memory. Then in September we went to America again. The BBC Club had arranged a charter flight to Philadelphia for £60 return, and so we decided on a three week stay. The Schilders met us at the airport and drove us down to their new home in Maryland. This was Deep Falls in Charles County, a large 18th-century mansion set in rolling countryside which even had its own private family graveyard. Unfortunately I had to carry on working; the Scottish Theatre Ballet was putting on a new production of Giselle and wanted to get back to Adam's original score without the various interpolations and accretions which have gradually crept into it over the years since the first performance. Peter Darrell, the choreographer, even cut out the well-known Peasant Duet in Act 1, which is by Burgmuller and not Adam. Luckily the BBC had a photostat of the original Paris score which I was able to use; but the Scottish Ballet could only afford an orchestra of 15 at the time, which made the music spare and incisive, but rather lacking in string tone The weather in Maryland was fine, and I sat on the verandah at Deep Falls in blazing sunshine working on the score, while Arthur Schilder was out at work. In the evenings we were splendidly entertained by the Schilders' many friends, the Marylanders and Virginians being just as hospitable as the Californians.

We paid a brief visit to New Orleans, staying on the edge of the 18th-century French Quarter. Here we not only enjoyed the delicious seafood and Creole dishes, but visited the famous Preservation Hall. For a dollar each we sat on rough benches and listened to the traditional jazz of the 20's played and sung by elderly negroes of both sexes, who performed for twenty minutes at a time with great gusto and enjoyment before retiring for a short interval, during which they no doubt had a drink or a puff of marijuana before returning with unabated energy for their next number. We also went on a paddle-steamer through the tropical bayous, where we made contact with the Deep South and viewed the muddy waters of the Mississippi. The French Quarter, with its latticed iron balconies, has been preserved exactly as it was and it still gives the feeling of old Louisiana before the Purchase, in spite of the teeming tourists.

"Hamlet” was revived at Covent Garden in the spring of 1971. Victor Braun had said that he would like to sing the name part again but, at the last moment, he threw up the role. Luckily Donald Rutherford was available and although he admitted that his voice was not really big enough for Covent Garden, he coped manfully with the part. The remainder of the cast were as in 1969, with the exception of my old friend Inia te Wiata ("Happy” to his friends) who had died. As before, the notices were mixed, but at least it was regarded as a serious new work and received widespread attention. This time we managed to get through four performances.

In the spring we visited Malcolm Arnold and his second wife Isobel, with their young son Edward, at their Cornish home near Padstow. Malcolm took us to see the May Day processions in Padstow, with their links with ancient pagan rites and their splendid May Day song. While I was there, I wrote a new setting of Chesterton's "Donkey" for Owen Brannigan; he wanted something less conventional than those he was used to. Unfortunately he died before he was able to learn it. Malcolm was very pleased at having been made a Cornish bard although a "furriner"; he comes from Northampton and his Cornish Dances and Padstow Lifeboat are splendid tributes to his adopted county.Sir Keith Falkner was a member of the committee which organised the Royal Concert, an annual affair designed to raise money for musical charities and patronised by the Royal Family. He had suggested that a different British composer should be commissioned to write a new orchestral work each year for it and, in 1971 the choice fell to me. Instead of loyal fanfares I decided to write a work based on Michael Ayrton's autobiography of Daedalus, “The Maze Maker”, an extraordinary piece of imaginative writing. Musically the work is a rondo, in that the "maze music” returns between the other episodes, but the music also follows the other events in the story, such as the copulation of Pasiphae and the Bull, the birth of the Minotaur, Daedalus' and Icarus' flight to Cumae, and so on. Each of the British Orchestras takes it in turn to give their services for the Royal Concert, and this year it was the turn of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. My work was in fact commissioned by the Feeney Trust, which has done so much to help British composers, and the first performance took place in Birmingham in November; it was repeated a few days later at the Royal Concert in London at the Festival Hall. The orchestra played very well under the the French conductor Louis Fremaux; the Royal Concert audience was quite different from the appreciative Birmingham one, consisting mostly of Society ladies who wanted to do their bit for charity, especially in the the presence of a Royal Personage. Princess Anne was present on this occasion; Michael and Elisabeth Ayrton shared a box with us, and we were all lined up to be presented to the Princess before the concert. She went straight down the line to Michael, having seen him on television, and they had quite a long conversation in the course of which she mentioned that her father liked to paint. "These Amateurs!" said Michael. I don't know what the Princess thought of my piece, as it came after the interval, but Keith Falkner told me afterwards of a conversation in the Royal Box in which the lady-in-waiting announced: "I never want to hear that piece again". "On the contrary", said Keith: "I would like to hear it again straight away".

During this period we had regular meetings on Sunday evenings with Basil Dean. As we lived only just round the corner from his house in Norfolk Road, we often visited his beautiful garden of which he was justly proud. We introduced him to another friend with a lovely house and garden, Helen Letts, the widow of Kenneth Letts of the diary firm, who lived in Elm Tree Road, near Lord's cricket ground, and the four of us, sometimes joined by other friends, had many pleasant "soirees" (as he called them ) at one or other of our houses. Basil was writing his memoirs at the time; they eventually appeared in two volumes, as "Seven Ages" and "Mind's Eye” He asked me to read each chapter as it was typed and I was able to help him with some suggestions; in return he presented us with signed proof copies of both volumes. It is absurd to recall that, when he was well into his eighties, he was turned out of his house by his landlords, who wanted to pull it down .Admittedly the other half of his semi-detached Regency house, which had been occupied by Larry Adler, had been left empty for many years and was in a parlous condition; but we felt that such drastic action was unnecessary. Basil's magnificent garden was destroyed too and he had to move to a flat near Baker Street Station which he professed to dislike intensely. He lived to the age of 89 in spite of having been knocked down by a car two years previously. A lot of actors suffered from his dictatorial methods of rehearsal but he had mellowed a great deal by the time I got to know him; I liked him very much, and enjoyed his racy memoirs of the theatre I was also glad to meet his daughter Tessa, his eldest son Winton, the expert on Handel opera and many other branches of music, and his lawyer sons Martin and Joe.

Fiona's mother Mollie was not at all well at this time; she was in and out of hospital with a disease that was eventaally diagnosed as cancer. She had to give up her room in Hampstead, as she could no longer cope by herself. It is difficult for us to have anybody to stay for more than a few days at Ordnance Hill, as the only spare room is a kind of passage-way leading to my studio where I work. However, as my mother, who was in her eighties, had vacated her flat in North Oxford and moved into a home for elderly people, I was able to go down there from time to time and allow Fiona to have Mollie to stay at Ordnance Hill. I was working on a Fantasy for cello and piano which my old friend Alun Hoddinott had commissioned for the Cardiff Festival of 20th Century Music, which took place in March 1972, and managed to finish it in Oxford. It was clear by this time that Mollie did not have much longer to live. Fiona was reluctant to leave her for even one night, but the Matron at the hospital persuaded her to join me in Cardiff for the performance. When we returned from Cardiff. we went straight to the hospital; Mollie suddenly opened her eyes and said to me: “I have been to such a beautiful place - why did I have to come back?" Her death the next evening, on 20 March 1972, was evidently peaceful.

Shortly afterwards I was asked by the organisers of the Bath Festival to write a work for singer, horn and piano, to be performed by Gerald English, Barry Tuckwell and Margaret Kitchin. I have always been attracted by Baudelaire's poetry and I set four poems from Les Fleurs du Mal; A une Dame Creole, Sisina, Obsession and l'Horloge, forming a kind of small cantata. The performance, in May 1972, went very well, and there have been quite a few performances of the work since. One critic remarked that it sounded very French, although it is not a pastiche of any of the French masters; it used the twelve-tone technique in a fairly free way, a method which I have used in several of my recent works.

We were saddened about this time by the death of Alan Rawsthorne, whom we used to see quite frequently at the George or the M.L. Club. He had not been well and had been forbidden by his doctor to drink any alcohol except wine, which he did not decline. He was always cheerful. Kenneth Clark's TV series "Civilisation" had just been published in book form, and he insisted on buying a copy of it for Fiona. He escorted her from the M.L. to Mowbray's Bookshop next door and, instead of giving the assistant a cheque for the book, he emptied his pockets to raise the required sum; this act left him almost destitute, with 7d to be exact, and so Fiona promptly walked him back to the M.L. and bought him a drink. Alan's friends will miss him very much; his pawky sense of humour was most salutory and he was a sincere and honest musician in the best meaning of the term. Although his works are rather out of fashion at present, I am sure that there will be a Rawsthorne revival before long. He had intended to rewrite his 'Kubla Khan" but never did so, and it was not until after his death that I felt free to begin my own setting of the poem.

In September Fiona and I went to Switzerland and France, this time by train. The Milhauds had found life in Paris too hectic for them and had gone to live in Geneva in a somewhat clinical apartment near the park. Milhaud's 80th birthday fell on 4 September, and we wanted to pay homage to him on the occasion. We spent a very unpleasant night in Dijon, where the cooking certainly failed to live up to the standard of the French Resistance banquet which I had attended there in 1955; on the following day I did not realise that only certain carriages on the train went through to Geneva, and we were deposited at a singularly dreary place on the Franco-Swiss frontier called Annemasse. After several hours delay, we reached Geneva where Madeleine Milhaud gave us a splendid meal on the night before Darius' birthday. After this Milhaud, who was tired, lay down on a hard wooden settee for a short time; he suddenly looked very defenceless and innocent. He spent most of his birthday working as usual; he was writing a cantata on a text by a Polish survivor of the concentration camps. The Milhauds gave a small party in the early evening for various friends, including ourselves, and then went on to what I gather was a hilarious evening with Arthur Rubenstein and other old friends, This was the last time that I saw Milhaud; he died two years later. I shall always be glad to have known him; his combination of genius with gentleness, modesty and helpfulness to others is very rare among important composers.

Fiona and I continued our journey to Provence, where we again stayed at the little village of Bagnols-en-Foret, this time at a villa rented by friends. Our hostess, who had sprained her leg and was unable to walk was extremely garrulous, and so her husband, Fiona and I made frequent visits to the village cafe.

About this time I began my setting of “Kubla Khan", which took me some time to finish. I wrote it for mixed chorus and large orchestra, with a short tenor solo in the 'damsel with a dulcimer" passage. I tried to make it as colourful and dramatic as possible, and I think it is one of the best things I have done but, as no one had commissioned it, I found it difficult to get it performed, British choral societies being rather conservative. The premiere eventually took place at an American university; of this more later.

Alun Hoddinott commissioned me to write another work for Cardiff University, this time for organ. In spite of my organ lessons at school with George Dyson, I had never really liked or got on with the instrument; my short Toccata alla Passacaglia for organ of 1957 was written in rather a hurry for a recital which never took place, and I was not very pleased with it. This time I decided to write a larger piece which would be --fairly brilliant in a rather more advanced style , and to get away from the ecclesiastical atmosphere usually associated with this instrument; the result was the Fantasy-Toccata of 1973 which was first played by the young Welsh organist Huw Tregelles Williams on the modern 2-manual organ in the Concert Hall of Cardiff University. This organ has a very brilliant tone, and the piece came off well. Since then it has been taken up by other organists, including Jennifer Bate and the 21-year-old Pamela Decker of Stanford, California, who mastered its difficulties with great aplomb.

One day Fiona and I were having lunch at an Italian restaurant in St. Martin's Lane where it was the custom for the ladies to be presented with a carnation on leaving. Cheered by this, and no doubt fortified by good Italian wine, we walked into the Renault showrooms in the same street, and Fiona, who had recently been sent some money from her late father's estate, decided to buy a Renault 4 - the first new car she had ever had.

We agreed to go on a motoring tour of Belgium and France, beginning with a visit to my Belgian cousins at Mirwart in the Ardennes. When we reached the village at lunchtime on our second day's drive, Fiona asked me to show her the way to my cousins' country cottage and was somewhat alarmed when I pointed to a vast mansion up the hill overlooking the village. The original chateau dated back to the Middle Ages and there are still dungeons underneath the house which belong to that period. The present chateau was built about 1720 in classical 18th century style; after my grandfather Schlich's death the ownership reverted to the Belgian branch of the family. In both World Wars it was occupied by German troops; but my cousins managed to conceal their wine cellar from the invaders by hiding it under a concrete floor.

After the Second World War the family could no longer afford to keep up the insurance payments on the house, which with its huge rooms and wooden panels would have burnt like matchwood in a fire. They persuaded the state of Luxembourg (the Belgian province, not the Grand Duchy) to take over its ownership provided that the family had the use of it in the summer months during the lifetime of its oldest member, a lady of about 70 at that time. The state authorities could hardly foresee that she would live to be 102! It was she who greeted us when we arrived. As was customary in my grandfather's day, there was a large family party staying at the chateau, and 23 of us, representing five generations sat down to lunch together. The copious array of servants who used to wait at table in the old days had of course disappeared, but a married couple from the village, with some assistance from local girls, coped very well. Fiona was intrigued by the ramifications of such a large family and, having found out the relationships between all of them, she was able to brief me before each meal as to who each of my relations was! We were all entertained by my cousins Jules and Albert for the few days we stayed there and had some beautiful drives through woods that had been planted by my grandfather.

After this pleasant visit we drove south to Frejus. Here we were welcomed by Ken and Trixie Buckel, a retired naval commander and his wife to whom we had been given an introduction by a friend. They owned two or three caravan sites at Le Pin de la Legue, near Frejus, and kindly offered us the use of one of them. Each caravan was surrounded by its own patch of trees, giving the occupants a fair amount of privacy, and there were shops, restaurants and swimming-pools a few minutes walk away through the pine trees. We enjoyed our stay very much.

On the way back we stayed at Fontainebleau, where a drunken Australian broke a window on the fourth floor of the hotel, showering Fiona's new car with jagged glass. On discovering this the next morning she was naturally incensed and complained to the hotel manager. He informed her that the culprit had checked out leaving his name and address as John Smith, Australia, and so any hopes of compensation were slim. From there we drove to St. Germain-en-Laye for a few nights. Here we left the car and went into Paris by the newly opened Metro extension. We saw Stephen Wendt and his willowy blonde wife Alison, soon, alas, to die of some incurable disease which she had bravely concealed from the world. We also saw Barbara Bray, who was working with Harold Pinter on a script for a projected film of Proust's "A la Recherche du Temps Perdu" - an impossible task, one might think, especially as the script contains no monologue, which the director, Joseph Losey, intended to replace with atmospheric photography and music. Barbara had suggested to him that I should write the music; when he showed me the script I was astonished at how well it had been done, and I was soon sketching out the “Vinteuil" sonata and septet mentioned in the book. The 'petite phrase' gave me trouble, especially as its various appearances of it are so minutely described by Proust; there are some suggestions about what melody he had in mind - a theme from Saint-Saens' first violin Sonata or an early work by Faure - and so I thought it best to write my own theme. I made no attempt to write a pastiche of Debussy or other composers of that period, but tried to write music which was atmospheric and would have sounded somewhat avant-garde at that time. So far the film has not been produced - it would obviously cost millions of dollars - but Pinter's script has been published and, when the American violinist Eudice Shapiro asked me to write something for her, I converted some of the "Vinteuil" music into "Three Romantic Pieces" for violin and piano; but I think the septet music would sound better with the ensemble mentioned by Proust.

Later that year, while visiting an exhibition of Edward Middleditch's work at the Serpentine Art Gallery, I ran into Julian Bream whom I had not seen for some time. He asked me to write a piece for solo guitar; he had quite a collection of British works written for him, including Britten, Fricker, Malcolm Arnold and Thomas Eastwood; he edited them for a series published by Faber's. I did not want to write something in the conventional Spanish style, but stuck to my own method of writing, not strictly twelve-tone, but atonal and chromatic. He found it rather difficult at first and I had to make a few changes for technical reasons, but we had a good session on it at his handsome Georgian mansion in Wiltshire, and eventually it emerged as a suite of five short pieces played without a break; I gave it the simple title of "Five". Julian has played it in recitals at the Queen Elizabeth Hall and elsewhere, as well as on the BBC.

For Christmas 1973 Fiona and I went to stay with my brother John, his wife Jenifer and their 11-year-old son Howard at their Oxfordshire house between Witney and Charlbury. Our mother was due to come over from Oxford on Christmas Day but on Christmas Eve John received a message from the Matron of the home in which she resided that she had died of a heart attack in the lift which was taking her back to her room after supper. This naturally cast a blight over Christmas, especially for Howard, whose Christmas tree was loaded with presents. But in some ways it was a good ending for my mother who was 84. Although perfectly alert mentally and enjoying life, she was finding it increasingly difficult to walk and her life ended on an upbeat, looking forward to our first family Christmas party for years. I felt glad that I had been able to visit her more frequently in recent years.

The three brothers

left to right

John, Michael, Humphrey

In the spring of 1974 the Cork Choral Festival celebrated its 21st birthday and invited all the composers who had been commissioned to write works for it in previous years to attend the celebrations. Fiona and I went over with our friend Beti Marshall who had recently divorced her husband and needed a break. We hired a car in Dublin and had a hilarious drive to Cork; although there was little traffic outside Dublin, drunken men scuttled across the road in front of our car from one pub to another and, on one occasion, a horse leapt over a hedge missing us by inches; In Cork we were invited to a ceremony at which honorary doctorates of music were presented by President de Valera, then in his nineties, to a number of elderly composers, including William Walton who had written a setting of the "Cantico del Sol" of St. Francis of Assisi for the Festival. The ceremony was a moving one in view of the age of the participants, and it was followed by a cheerful party, as indeed were all the evening concerts; we usually seemed to end up in the Lord Mayor's Parlour where ww were generously entertained. The composers who were not having works performed had no official duties and just came for the ride, making a pleasant break for us all. We spent one day right out in the sticks at Ballydehob, not far from the west coast, visiting Helen Letts' sister-in-law who kept two donkeys in her field just for the pleasure of their company. Finding our way back to Cork was a trifle difficult, as very few of the people from whom we asked the way understood anything but Gaelic - which shows that the efforts of the Irish Government to promote the language have not been in vain.Back in Dublin we had an extraordinary encounter with Reggie Smith and some of his Irish friends who kept walking in and out of the Bailey bar in a group, saying "Hulloo now”, "Good-bye now", "Hulloo now" and so on ad infinitum. Our journey back to England was rather fraught; as Beti had to work on the Monday we had to travel on the Sunday We reached Liverpool Lime Street Station at an unearthly hour and found nothing open while waiting for the train; not even a cup of coffee was available. When the train eventually arrived it took seven hours to get to London instead of the usual two and a half, travelling via all sorts of unlikely places such as Birmingham.

The Cheltenham Festival that year included an evening with the King's Singers devoted to the Seven Deadly Sins, and seven composers were asked to contribute a piece on each of the sins. I was allotted Pride - not that I am a particularly proud person - and P.J. Kavanagh, the director of the Cheltenham Poetry Festival, found an amusing poem for me to set, "Rhyme Rude to my Pride", by James Michie. I didn't attempt to exploit the extreme vocal pyrotechnics of which the King's Singers are capable, but wrote a fairly straightforward setting which I think went down quite well. Elisabeth Lutyens wrote an ingenious setting of "Sloth", for which she provided her own poem, and most of the other pieces were short and to the point, except for one overlong semi-dramatic cantata.

In the summer of 1974 we visited my sister-in-law's sister Antonia Poole at her cottage in the Dordogne, to which she had retired after holding down a post at UNESCO in Paris for some years. We drove via Southampton and Le Havre, and were able to reach Mont St Michel at 10a.m and so had time to appreciate its beauty, arriving before the main rush of tourists. The Dordogne I found disappointing after Provence, despite some nice country scenery and some pleasant hilltop villages; the weather was wet and Bergerac seemed a boring place, unworthy of its famous fictional son Cyrano. On the way to the south we spent the night at Albi which we much preferred, both architecturally and for its splendid Toulouse-Lautrec museum; I had not realised that he was such a good landscape painter in his early days. As Fiona had wanted to see the white horses of the Camargues we took that route and went on to Aries, where we were rewarded by a view of the amphitheatre the following morning.

By the simple expedient of buying a 2½d ticket in a raffle organised by the Labour Party, Fiona - had won £500 on horse called Dahlia, which, ridden by Lester Piggott, won the King George and Queen Elizabeth Stakes in July. This win enabled her to invite her sister Sheila to escape from her family problems in South Africa and stay with us for a few weeks at Ordnance Hill in October. Although Sheila found the cold climate of London rather trying after the heat of Durban, she was glad to be with Fiona again and we were able to give her raspberries for breakfast, her favourite fruit and unobtainable in South Africa.

I wrote two more pieces that year (1974). My friend the actor Hugh Burden persuaded me to set John Donne’s "Nocturnall upon S. Lucie's Day" being the "Shortest Day" a poem of almost unrelieved gloom but which I found interesting and dramatic; Gerald English had asked me to write a long song for him, and I was glad to have this opportunity of fulfilling this request. Then in the autumn Basil Ashmore, who had been concerned with theatrical ventures of various kinds for many years, decided to put on a festival at Chalfont St. Giles in honour of the tercentenary of Milton, which he felt had been neglected. He asked me to write a work for cello and piano, to be played by the redoubtable brothers Rohan and Druvi de Saram. I decided on two contrasting pieces, Il Penseroso e L'Allegro, thus reversing Milton's order. The concert was not very well organised; in spite of the presence of several well-known actors and actresses who read Milton's poems, and in spite of the admirable playing of the de Saram brothers, the evening lacked coherence and went on too long - a pity, as it was a good idea.

In 1975, we paid our last visit to Provence before our American trip. We spent one night at Salon and it was not till we got to Cannes, where the Buckels had found a small flat for us, that I discovered my briefcase was missing from the car, although everything else, including some bottles of spirits and cartons of cigarettes, was intact. The briefcase was only important because it contained the MS of a work which I was writing for the U.S. Bicentenial (more of this in the next chapter) and I didn't want to have to start it all over again. I wrote to the police in Salon and shortly afterwards received a letter notifying me that the briefcase had been found. I went to Salon to retrieve it; the contents were intact. Apparently the thief, who had forced open a window of the car during the night, was fed up when he discovered that the case contained no money or valuables and had thrown it over a hedge; so I was lucky. We spent a pleasant time in Cannes, seeing the Buckels and their friends, but it is not an exciting city, especially at night, when everything closes at 8 except the tourist hotels and restaurants along the Croisette.

We returned to London in time for my 60th birthday on 26 August. The BBC celebrated this by playing "Labyrinth" at the Proms the LSO gave an excellent performance under the young German conductor Bernhard Klee. Michael Ayrton, (although not in the best of health as he was suffering from osteoarthritis) came to the concert and to a small party which we gave afterwards. I was very shocked when he died towards the end of that year from a sudden heart attack; apart from the fact that we had been good friends for more than thirty years, I had a great admiration for his genius as painter, sculptor, writer and speaker. At the time of his death, he was working on a series of television scripts called "The Question of Mirrors" for the BBC; this was an extraordinarily broad-based project and he had asked me to look after the musical side of it. After his death a single programme was broadcast which contained extracts from his scripts and appreciations of Michael by his friends including James Cameron, Frederic Raphael and myself. People have often criticised Michael for spreading his genius in too many directions. I don't agree with this criticism; everything he did was well done and I am sure that posterity will have a higher opinion of him than is fashionable at present. He was one of the most astonishingly gifted people that I have ever met.

1975 was the 150th anniversary of British Rail and, shortly after the end of the Prom season, they hired the Albert Hall for a concert of railway music. This included the first British performance of Berlioz' Chant des Chemins de Fer, written in 1846 for the opening of the Paris-Lille railway. Although not one of his greatest masterpieces (it was written in three days!), it is certainly worth performing. I made a new English translation of the words, as the one in the printed score bears little relationship to Jules Janin's text. Richard Lewis was the excellent soloist, with the John Alldis and London Philharmonic Choirs and the RPO under Charles Groves. Bernard Kaukas, the chief architect of British Rail, had had the idea for the concert and he appointed a small committee of fellow members of the Savage Club to draw up the programme. This included Honegger's Pacific 231, some railway films, the Ted Heath Band, Vivian Ellis' Coronation Scot and a Grand Finale concocted by Alan Civil on the theme of "Oh! Mr. Porter” and “The Runaway Train". My own contribution was a setting of another T.S.Eliot poem, Skimbleshanks the Railway cat, for baritone (John Gibbs), chorus and orchestra. The performers also included Kenneth More as compere and the trumpeters of the Royal Militarv School of Music But British Rail had no idea of how to organise a concert; there was practicallv no publicity for it, the programme was badly laid out and, as a result, the hall was by no means full. One might have thought that railway buffs from all over the country would have wanted to attend.

I had joined the Savage Club in 1972; I am not much of a clubman, but it is very different from the type of club in which elderly gentlemen snooze for hours in leather armchairs behind copies of "The Times". Savage members are friendly and talk to one another whether they know each other or not. Most of them are artists or belong to other entertainment professions, but "shop" and briefcases are discouraged. Throughout the winter there are fortnightly evening entertainments in which artists of the calibre of Alan Civil or John Wilbraham give their services for nothing. I have been glad to sit on the Entertainments Sub-Committee for some years and to help to organise some of these evenings. As there are numerous Ladies Nights, I did not have to leave Fiona at home whenever I went to the club.