QUADRILLE WITH A RAVEN

Memoirs By Humphrey Searle

Chapter 9: HITLER'S WILL

The troop train clanked ponderously across an insecure-looking Rhine bridge hastily constructed by the Royal Engineers and eventually deposited us at Rhine Army HQ; this was in August 1945, and the war with Japan was almost over. The HQ was situated in Bad Oeynhausen, a rather dreary little spa in the middle of the North German plain, made drearier by the fact that the entire German civilian population had been evacuated from it, and the town contained nothing but troops. I was assigned to an office in HQ itself. Our job was to track down the remnants of the Gestapo and 55 personnel who were still at large and to lock them up - needless to say, most of them when caught were released before long. The work entailed sorting out endless information obtained from German prisoners about the possible whereabouts of these people and passing it on to the various HQs of the various corps in whose territories the wanted men might be found - or, in certain cases, to the American and French Occupation Forces. We didn't seem to have much contact with the Russians. We worked long hours, six days a week; but there was very little to do outside office hours, once we had visited the two cinemas in the town. We mostly congregated in the mess, where German Steinhager gin cost two old pence a nip; this, if not actually lethal, was liable to cause severe hangovers.

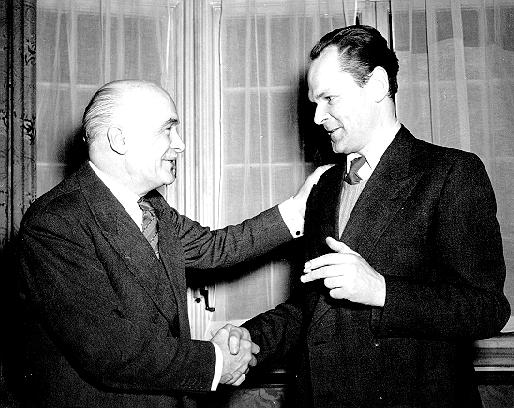

Humphrey with Louis Burdet, the French Colonel in the Resistance who taught Humphrey elements of commando warfare.

Luckily I met some people I had known previously. John Willett, a Winchester friend who later became editor of the Times Literary Supplement, was going on a mission to Vienna, and I gave him a letter to take to Webern, as civilian mail was more or less non-existent at that time. A few weeks later I was appalled to receive a letter from John giving me the tragic news of Webern's death; he had been shot by a tiigger-happyAmerican soldier. I was angry rather than upset I went straight back to my billet, which was freezingly cold, and began a piece which later became my Second Nocturne for chamber orchestra; its opening theme expresses my feelings of protest. It seemed so absurd that this should happen to a man who was still at the height of his powers - he was 61 - and who was about to return to Vienna to undertake important work which would probably have changed the entire aspect of music in Vienna and the rest of the world.

Later in the year Hitler's will was discovered by accident in the clothing of a German prisoner, and I was put in charge of the enquiries which followed. The Oxford historian Hugh TrevorRoper came over from the War Room in London from time to time to supervise the work, the results of which were later published in "The Last Days of Hitler”. Our object was to prove that Hitler really was dead, and to prevent the emergence of some kind of resurrection myth which might encourage the Nazis to try to seize power again. We discovered that there had been two other copies of the will, and were able to track down the two men who had taken them out of the Bunker at the time of Hitler's death. The Russians were not at all co-operative, and as the Bunker was in the Russian sector of Berlin our enquiries were somewhat handicapped, especially as some of the main witnesses were in Russian hands. (In fact the Russian version of the story did not emerge till many years later). However we were able to assemble sufficient first-hand witnesses to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that Hitler and Eva Braun had committed suicide in the Bunker and that their bodies had been burned in the grounds. Meanwhile I made English translations of Hitler's personal and political testaments and also of Goebbel's will, which had been smuggled out of the Bunker with the others; these were published in due course when the story broke towards the end of the year.

We did occasionally have some outside entertainment; the Sadler's Wells Opera visited us during the winter, and I was able to meet some old friends in the company such as Elizabeth Abercrombie, Warwick Braithwaite and Trefor Jones. And I helped to organize some entertainments myself; at Christmas time we put on a musical version of "East Lynne", which my Oxford friend John Irvine produced and in which he also played the villain. Another Winchester friend, Anthony Smith-Masters, set the lyrics to splendid pastiches of Victorian tunes, and I wrote the incidental music for the scene changes and conducted a small orchestra in the pits. Bad Oeynhausen had a very pleasant medium-sized theatre which had not been bombed in the war. At first the audience of soldiers was inclined to take the play so seriously that we had to install a claque to hiss the villain and cheer the hero and heroine. They soon got the message and the last night was a riot.

In addition I conducted some orchestral concerts; we had some Forces musicians whom I was able to supplement with players from a former German school of military music at nearby Buckeburg. We performed popular works, Beethoven's 5th, Schubert's Unfinished and a choral version of Strauss's Tales from the Vienna Woods, and also Bach's 5th Brandenburg Concerto, with an excellent officer colleague as piano soloist, and the three well-kn

own pieces from Berlioz' "Damnation of Faust". I also wrote a Highland Reel, based on tunes I had heard in Scotland during the war, and it had its first performance here. The concerts were invariably fully attended and the audiences enthusiastic, but I was severely reprimanded by the Control Commission for "fraternising with the enemy". Apparently it was an offence to form a joint Anglo-German orchestra!

I was demobilised in March 1946, and managed to visit some of my Antwerp relations on the way back to England. They seemed to have survived the war without too many privations, though their chateau at Mirwart had been severely damaged when the Germans occupied it. (However they failed to discover a cache of wine which my cousin Jules had prudently buried under one of the towers). After six years I was glad to be returning to civilian life, though my war service had been interesting in many ways and I was certainly luckier than many of my colleagues.