Seen and Heard Art

Review

'Turner Whistler Monet'

- Tate Britain, London (AR)

Tate Britain's blockbuster sell-out ‘Turner

Whistler Monet’ exhibition (sponsored by Ernst & Young)

is the first to juxtapose such divergent artists and reveals the

importance of the American born Whistler as a linking figure between

Turner, the forerunner of Impressionism, and the archetypical

Impressionist, Monet. This exhibition reveals that Turner, Whistler

and Monet were all in a sense Impressionists - or even Sensationists

- as they were all influenced by the Thames’ haze and smog

– smaze - a combination of man-made industrial pollution

and man’s own sensations of sunny and stormy weathers. All

three made the successful transition from realism to the more

subtle art of sensation: the true birth of Sensationism.

A reviewer cannot possibly do such a mammoth

show justice and it really required several visits to take in

the intensity of the images. After absorbing so many sublime sensations,

I reached an almost comatose state of saturation and knew it would

be impossible to take in anymore. Here Stendahlism threatened

on more than one occasion - I felt faint when confronted by the

intense radiance of the magnificent Monets - they were the stars

of the show eclipsing even such luminaries as Turner and Whistler.

Whilst the exhibition catalogue serves as a useful

reference it fails to reproduce the sheer intensity of Monet,

the subtle evanescence of Whistler or the dramatic dynamism of

Turner. Even utilising today’s high standards of colour

reproduction the illustrations appeared watered down and opaque,

simply lacking the sensation and subtlety of the ‘originals’.

The well-planned layout of the exhibition allowed one to make

immediate visual comparisons to how each artist approached similar

subjects such as townscapes, riverscapes and smazescapes and sensation

states - the sensation of mist and smog in the city. Whistler’s

serene Nocturne in Grey and Silver (1873-75) is arguably

his finest painting of the show with its mesmerising mist, distilled

cool silence, appearing almost Rothkoesque. It is also strikingly

similar in moody mistyness to Monet’s mauve and lavender

The Seine at Giverny, Morning Mists, 1897. Whilst both

images are painted in different styles and times of the day, the

Whistler, depicting evening mist, is painted with invisible brush

strokes, whilst in the Monet the brush marks are visible and form

the image of the morning mist. Both have a strikingly similar

mesmerising and shimmering quality arrived at by differing techniques.

Whistler’s subtle translucence is partially achieved by

the thinning down of oil paint with turps – peinture

al’essence – perhaps partially derived from observing

Turner’s opulent watercolours.

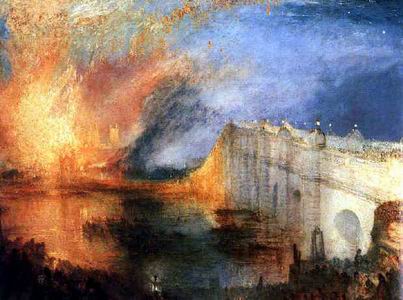

Whistler’s night-time views of the Thames, The Nocturnes,

were painted from memory in the studio just as Turner’s

Burning of the Houses of Parliament (16th October, 1834)

was painted in the studio from a series of pure watercolour sketches

he painted ‘live’ in a boat on the Thames, observing

the action as it happened: seeing these vibrant watercolours on

display for the first time reminded me of the fiery intensity

of Emil Nolde’s watercolours in their burning primary colours.

Whereas Turner painted the Houses of Parliament literarily in

flames, Monet painted the Houses of Parliament, Sunset

(1904) where river, sky and Parliament all appear to be aflame

with the setting sun. Whereas Turner depicts Parliament burning

Monet actually sets the Thames alight as liquefying flames: Parliament

is floating in a river of fire.

In stark contrast to Turner and Monet, Whistler’s sombre

and serene palette and the melancholic moods of his Nocturnes

are strikingly reminiscent of Jawlensky’s dark and brooding

Mediations. Whistler’s Nocturnes nurture the murky moments

and moods of the twilight-zone, hovering between light and dark,

smudging the vision of the viewer and producing a silent shudder.

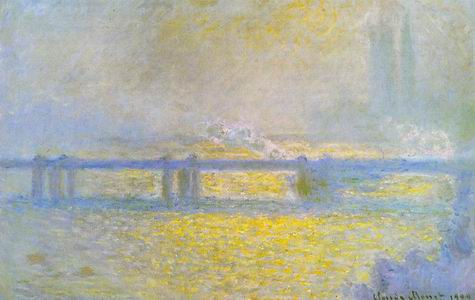

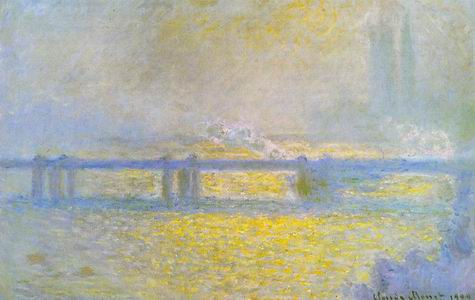

For me the most stunning, dazzling and mesmerising painting was

Monet’s Charing Cross Bridge Overcast Weather (1900)

and no reproduction I have ever seen does it full justice. The

sparkling and shimmering orange flicks of paint become gold tears

reflecting the boiling hot sun.

At the end of the exhibition we are confronted with Monet’s

murky Palazzo Contarini (1908) whose haunting and ghostly

qualities return us to the twilight zone of Whistler’s mesmerising

Nocturnes: the stone masonry has a soft jelly-like, shimmering,

melting quality as if sinking into the lagoon which reflects and

refracts it. The Palazzo is truncated and severed by the frame

giving the impression that it is sinking and being devoured by

the violently lapping water and creating the sensation of a crushing

claustrophobia. Here the Palazzo is under siege by the invasive

rising waters of the lagoon.

Monet’s dazzling, muscular and musical

image of this vibrating, sinking palace left me with a floating

feeling, and I left elevated and dazed. Yet, the only problem

with this outstanding exhibition was that there was not one bad

image in it; one had to censor what one saw in order to prevent

becoming overwhelmed by sheer bedazzlement and fatigue.

Alex Russell