CD Reviews

CD Reviews MusicWeb

Webmaster: Len Mullenger

Len@musicweb.uk.net

[Jazz index][Purchase CDs][ Film MusicWeb][Classical MusicWeb][Gerard Hoffnung][MusicWeb Site Map]

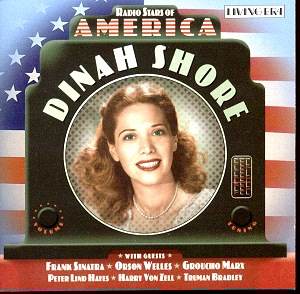

Dinah Shore - Radio Stars of America

That Old Devil Moon/Mr and Mrs Perriwinkle/No

Greater Love

Counting the Days/The Story of Harry and Frank/You’ll

Never Walk Alone

Oh Why, Oh Why Did I Ever Leave Wyoming/Down

on the Ranch/Anniversary Song

Georgia on My Mind/Realism in Radio

Let It Snow/Forbes Schneider Presents/Congratulations

Groucho On Your Contract

Here’s Dinah

Dinah Shore with Peter Lind Hayes, Frank Sinatra,

Orson Welles, Groucho Marx, Harry von Zell,

Truman Bradley

Radio excerpts recorded 1942-47

![]() LIVING ERA CD AJA 5597

[70.32]

LIVING ERA CD AJA 5597

[70.32]

Dinah Shore was in her radiant youth when she broadcast these radio programmes. The majority were for the Birdseye Open House but the last, reflecting her popularity in wartime, was her own Here’s Dinah show. The format for the Birdseye excerpts is much the same; songs and bantering sketches, the latter enlivened by Groucho Marx (a touch downbeat), Orson Welles (taking no prisoners with a rusty script) and Frank Sinatra (cocky and sharp).

Shore’s break had come at the end of the 1930s when as a twenty-two year old she broke into network shows and enjoyed popularity with her RCA Victor Bluebird discs. She began – I’d forgotten this – as the regular singer with The Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street, whose NBC show was so popular; it was certainly popular enough for Sidney Bechet to wave his magnificent soprano saxophone in their direction on air and disc, however novelty orientated their Dixieland may have been.

Fresh and pure she sings with great warmth. She’s a natural giggler and by the time of these broadcasts an adept radio creature, though not quite quick witted enough to deal with some of the more off the cuff patter from the bigger stars, though her wry laugh is an adept foil. The first sketch with regular sideman Peter Lind Hayes is rather slow to take off though the second, with its Down On The Ranch motif brings us the essence of her pure, lyric voice, a dead centre of the note affair and delicious.

Naturally there are plugs for Birdseye products, the firm that sponsored most of the shows, but rather more interesting than matters of commercial exploitation are the sly moments that lift these sketches and songs out of the ordinary. Orson Welles, for instance, getting nowhere with a duff script, announces to the audience – "I can’t be funny – but I can be rude" – with the most perfect timing. And Sinatra gives us a sensitive You’ll Never Walk Alone.

Aficionados of such things will want to know that the sound varies from show to show, that there are some acetate thumps and that there are also a few rather abrupt track ends. Otherwise they are more than serviceable transfers and have decent notes as well.

Jonathan Woolf