CD Reviews

CD Reviews

MusicWeb

Webmaster: Len Mullenger

Len@musicweb.uk.net

[Jazz index][Rock][Purchase CDs][ Film MusicWeb][Classical MusicWeb][Gerard Hoffnung][MusicWeb Site Map]

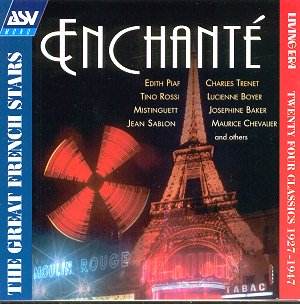

ENCHANTÉ - THE GREAT FRENCH STARS

Maurice CHEVALIER

Louise (with Leonard Joy and his Orchestra, New York 1929)

Valentine (with Tom Griselle and his Orchestra, New York 1929)

MISTINGUETT

Ça c'est Paris (with Fred Mêlé and his Jazz du Moulin Rouge, 1926)

Au fond de tes yeux (with Marcel Cariven and his Orchestra, 1936)

Joséphine BAKER

J'ai deux amours*, La petite Tonkinoise (with Adrien Lamy, vocal* and Le Melodic Jazz du

Casino de Paris/Edmond Mahieux, 1930)

Lucienne BOYER

Parlez-moi d'amour (with Bruno Codolban and his Orchestra, 1930)

Mon p'tit Kaki (with Wal-Berg and his Orchestra, 1939)

Tino ROSSI

Vieni, vieni (with Pierre Chagnon and his Orchestra, female chorus, 1934)

Chanson pour Nina (with Marcel Cariven and his Orchestra, 1935)

Yvonne PRINTEMPS

Plaisir d'amour (with Madame Peltier, harpsichord, 1931)

Lys GAUTY

Le chaland qui passe (with J. Jacquin and his Orchestra, 1933)

DAMIA

La guingette a fermé ses volets (with Pierre Chagnon and his Orchestra, 1934)

Django REINHARDT (guitar)

Djangology*, Nuages (with The Quintet of the Hot Club of France and Stephane Grapelli, violin*, 1935*, 1940)

Charles TRENET

Boum! (with Wal-Berg and his Orchestra, 1938)

La mer (with Albert Lasry and his Orchestra, male chorus, 1946)

FRÉHEL

Tel qu'il est, il me plaît - Tango (with Maurice Alexander and his Musette Orchestra, 1936)

Suzy SOLIDOR

La danseuse est Créole (with Raymond Legrand and his Orchestra, 1947)

Jean SABLON

J'attendrai, Vous qui passez sans me voir* (with Wal-Berg and his Orchestra and Alec Siniavine, piano*, 1939, 1936*)

Edith PIAF

Tu es partout (with Paul Durand and his Orchestra, 1943)

La vie en rose (with Guy Luypaerts and his Orchestra, 1946)

Les trois cloches (with Les Compagnons de la Chanson, 1946)

ASV CD AJA 5364 [76' 37"]

Crotchet

To the stern eye of the classical musician the above titling is all upside-down and inside-out, for the names in heavy type are the artists (principally vocalists), followed by the titles of their songs (or pieces) and their supporting artists, with the composers and authors nowhere. This information is all contained in the booklet which is remarkably informative given the space available. The documentation angle is important (we also get full dates, where I have listed only the year, and the original record numbers) since this type of repertoire is often thrown at the public with minimum information, relying on the selling power of the artist's name. I have before me, for example, a double-CD Piaf Album, Songs of a Sparrow, issued by Snapper Music (SMDCD 313), which lists neither supporting artists nor dates.

Yet this situation reflects the real priorities of a particular musical world. The classical singer is there to interpret a composer who is the real protagonist of the performance and he tries with all humility to be the vehicle through which the composer reaches the public. (Well, one wishes to think it's like that …). But there is another way of doing things. In the light music world the singer is there for him- or herself, there to give us a song. The songs themselves may be negligible, on paper, ephemeral things knocked up for the occasion in the style of the day by composers almost interchangeable among one another, yet serving their purpose. They act as vehicles by which the singer displays his or her art, his or her personal timbre or sense of timing. Most classical singers have a secret (or not-so-secret) hankering after a situation of the "XYZ sings and never-mind-what-he-sings" variety and artists as different as Beniamino Gigli and Peter Dawson have shown that the two worlds are not mutually incompatible.

But is the one situation necessarily "better" than the other? Throughout most of the history of music the composer has been more artisan than artist, a supplier of material for local musicians and contexts. Probably neither Bach nor Schubert saw themselves as anything more. It was the romantic age which raised the composer to the level of a demi-God, a position he has occupied for barely two centuries. Yet the composer as artisan remains an essential commodity. We hear his work every time we switch on the radio or the TV, and where would we be without him?

So here it is the artists that count, though it does seem right to add that Reinhardt, Trenet and (in her first two items) Piaf present works of their own. Basically we have a history of the French chanson for, although it is not specifically intended as such, only three items do not fit this theme, and they seem not to belong to the programme. Yvonne Printemps's anachronistically warbling Plaisir d'amour might be enjoyable in a different context but surely some more relevant example of her art could have been found? In the case of the two purely instrumental items by Django Reinhardt, one of which includes scintillating work from Stéphane Grapelli, the justification is that they are very good and lead one to hope that ASV will explore this field further. But for the rest, what good singers they all are, with clear, effortlessly-produced, well-focussed voices, so communicative that even those with limited French will have a fairly clear idea of what they are singing about. With Trenet and Sablon we can note the transition from projected singing to microphone-singing, but within their chosen means these are excellent artists. The sepia-coloured orchestras all provide unfailingly apt support. A prevailing sense of melancholy, even during the livelier pieces, perhaps characterises the whole epoch and found its highest expression in Edith Piaf, who rightly concludes the programme.

As a check on the transfers I compared this version of La vie en rose with that of the Snapper Music album mentioned above, and also with that on an EMI-Pathé compilation (724357626525). At first I found the latter to be more vivid, but later it became a little tiring to the ear with its emphasis on the more abrasive aspects of Piaf's timbre. Alongside its sandblasting qualities this voice also has a sweetness which accounts for its affecting melancholy. The Snapper Music transfer goes almost too far in the other direction, a low-level, slightly faded effect. This has its attractions but the new ASV version seems to get the best of both worlds. So all in all this looks like an ideal introduction to the French chanson and deserves the attention even of more "serious" listeners, for the chanson enshrines an essential part of French culture.

The Italian origin of two items - Le chaland qui passe is by Cesare Bixio and was originally sung by Vittorio De Sica in a 1932 film while J'attendrai derives from Olivieri's Tornerò - prompts me to hint that ASV might well take a look at the Italian canzone of this same period.

Christopher Howell