BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

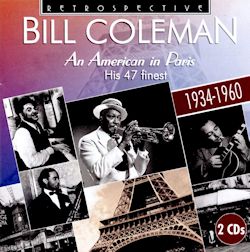

BILL COLEMAN An American in Paris; His 47 finest, 1934-1960

|

CD 1

1. What’s The Reason I’m Not Pleasin’ You?

2. Georgia On My Mind

3. I’m In The Mood For Love

4. After You’ve Gone

5. Joe Louis Stomp

6. Believe It, Beloved

7. Dream Man

8. I’m A Hundred Percent For You

9. Baby Brown

10. Rosetta

11. Stompin’ At The Savoy

12. Sweet Sue, Just You

13. Hangin’ Around Boudon

14. Japanese Sandman

15. Exactly Like You

16. Hangover Blues

17. Indiana

18. Rose Room

19. Bill Street Blues

20. After You’ve Gone

21. I Ain’t Got Nobody

22. Bill Coleman Blues

23. In A Little Spanish Town

24. ’Way Down Yonder In New Orleans

25. I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate

26. Three O’clock Jump

CD 2

1. I Never Knew That Roses Grew

2. Linger Awhile

3. Just You, Just Me

4. What Is This Thing Called Love?

5. St Louis Blues

6. Liza

7. I Can’t Get Started

8. Don’t Blame Me

9. Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby!

10. If I Had You

11. I’m Confessin’

12. Indiana

13. Blues In My Heart

14. Limehouse Blues

15. Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams

16. Idaho

17. Blue, Turning Grey Over You

18. Caravan

19. Honeysuckle Rose

20. I’ve Found A New Baby

21. ColemanologyHere is a twofer containing more than a quarter century’s worth of the recordings of the trumpeter’s trumpeter, Bill Coleman. Though he would continue to record for another two decades until 1980, the year before his death, this necessarily compact salute allows the listener to enjoy his crisp, incisive, skipping soloing, firm taut lead and generous approach both to tonal beauty and to lyrical invention.

Kentucky-born Coleman was a rover. He travelled to Paris with Lucky Millinder’s band in 1933, which gave him a strong taste for French life; after the war, in the 1950s, he returned to the city where he lived for the rest of his life. The earliest discs chart those early Parisian years whether with his trio with the virtuosic pianist Herman Chittison or local musicians. His springy, vitalising playing, aided by Chittison’s sub-Hinesian loquacity, shows strong Armstrong-derived elements – as was almost inevitable – and it’s good to hear guitarist Oscar Aleman soling on a 1936 track, Coleman’s composition Joe Louis Stomp. Despite claiming to have been drink-sodden in his New York Fats Waller sessions he sounds commendably in control, taking the role of his exact contemporary Herman Autrey, alongside Gene Sedric in the front line. Even more classic, however, are the Paris recordings with Dicky Wells, Django Reinhardt and rhythm, with Wells’s velvet buzzing soloing much prized by lovers of the genre.

He had a repertory company of musicians in Paris with whom to record – Hawkins-inspired tenor player Alix Combelle is fiery onExactly Like You, Grappelli and Coleman swap marvelous trades on Bill Street Blues (a punning Coleman original) and there’s the famous duet with Django on Bill Coleman Blues. The vogue for chamber jazz was at something like its peak when, in April 1940 and back in NYC, Coleman recorded with Joe Marsala, Pete Brown, Carmen Mastren and Gene Traxler as ‘Joe Marsala and his Delta Four’. Listen out for jump master Pete Brown’s huffy-puffy alto sax.

There are simply too many exemplary examples of the fast company Coleman kept to do justice to the great music heard in this filled-to-the-gunnels twofer. Whether it’s recording with Teddy Wilson’s little outfit or alongside Lester Young in 1943 with Wells again – sounding a bit hoarse-toned – and Ellis Larkins; or back in Paris for four bop-tinged tracks with the combustible Don Byas (wrongly described in the track listing as playing alto). Byas, never a man short on self-confidence, plays with pugilistic brilliance on Liza. Meanwhile Coleman shows independence from Bunny Berigan’s template on I Can’t Get Started and dusts down three standards with his French band in exemplary new arrangements– Yes, Sir, If I had You and I’m Confessin’. Tenor player Guy Lafitte proves excellent, pianist André Persiany less consistently so. Coleman played at a number of recorded concerts and some have been preserved here, allowing musicians to stretch out longer than had been possible in the days of 78s or even LPs. Sometimes this is all to the good, and occasionally, as in Limehouse Blues, a 1957 track with the New Orleans Wild Cats, the result is a bit of a Bechet-style carve-up. The six tracks with pianist Henry Chaix and his little band offer poised lyricism.

Digby Fairweather’s notes are rightly admiring of Coleman and cite his autobiography as a welcome repository of information. One can also add that in the biographical slipstream there is a warm chapter on Coleman in John Wain’s 1969 Letters to Five Artists; the trumpeter and the writer were firm friends.

The fine transfers seal a splendid retrospective package.

Jonathan Woolf