BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

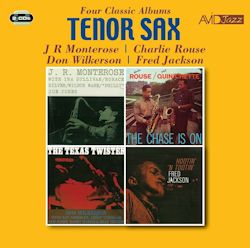

Tenor Sax Four Classic Albums |

CD1

J.R. MONTEROSE – J.R.Monterose

1. Wee Jay

2. The Third

3. Bobbie Pin

4. Marc V

5. Ka-Link

6. BeauteousJ.R. Monterose (tenor sax), Ira Sullivan (trumpet), Horace Silver (piano),

Wilbur Ware (bass) ‘Philly’ Joe Jones (drums).

rec. New Jersey, October 21, 1956

CHARLIE ROUSE – PAUL QUINICHETTE – The Chase Is On

7. The Chase Is On

8. When The Blues Comes On

9. This Can’t Be Love

10. Last Time For Love

11. You’re Cheating Yourself

12. Knittin’

13. Tender Trap

14. The Things I LoveCharlie Rouse (tenor sax), Paul Quinichette (tenor sax), Hank Jones (piano, tracks 8, 11), Wynton Kelly (piano, 7, 9-10, 12-14), Freddie Greene (guitar, 8,11), Wendell Marshall (bass), Ed Thigpen (drums)

rec. New York, August 29 1957 (tracks 7,9-10, 12-14) and September 8 1957 (8,11)

CD2

DON WILKERSON - The Texas Twister

1. The Twister

2. Morning Coffee

3. Idiom

4. Jelly-Roll

5. Easy To Love

6. Where Or When

7. MediaDon Wilkerson (tenor sax), Nat Adderley (cornet, tracks 1-3, 4, 7)), Barry Harris (piano),

Leroy Vinnegar (bass, 2-3,7), Sam Jones (bass, 1, 4-6), Billy Higgins (drums)

rec. Los Angeles, May 19-20, 1960

FRED JACKSON –Hootin’ “N” Tootin’

8. Dippin’ In The Bag

9. Southern Exposure

10. Preach Brother

11. Hootin’ ‘N Tootin’

12. Easin’ On Down

13. That’s Where It’s At

14. Way Down HomeFred Jackson (tenor sax), Earl Van Dyke (organ), Willie Jones (guitar)

Wilbert Hogan (drums)

rec. New Jersey, February 5, 1962

Like other recent anthologies from Avid (Jazz Trumpet, Jazz Piano, etc.), Tenor Sax is a 2-CD set made up of four reissued albums. But this time you get an introduction to five, rather than four, tenor saxophonists, since one of these albums features two tenors. None of the five could be regarded as more than second-rank players, at best, but all four albums offer some worthwhile and interesting listening.

Of the five tenors two, Don Wilkerson and Fred Jackson, made their initial reputations in Rhythm and Blues, rather than jazz. The other three grew up, musically speaking, more or less exclusively within the jazz tradition, though no doubt economic necessity encouraged some forays into more popular idioms.

I suppose Charlie Rouse is the best-known name here, chiefly because of the years he spent in the quartet of Thelonious Monk, between 1959 and 1970. Rouse (1924-1988) worked, from the mid 1940s onwards, in the bands of Billy Eckstine, Dizzy Gillespie and Tadd Dameron. Brief spells with both Basie and Ellington followed. So, by the time of this recording, in 1957, when largely working freelance, he had a good deal of experience behind him. Paul Quinichette (1916-1983) had early experience with Jay McShann and later worked with Louis Jordan and Count Basie (1952-3). He also worked, in the next few years, with Benny Goodman, Nat Pierce and Billie Holiday. Rouse’s characteristic sound on the tenor has been described as “nasal”, a clear contrast with the lighter sound of Quinichette, much influenced by Lester Young. The difference can be heard very clearly when the two exchange ‘fours’ on ‘This Can’t Be Love’ (Rouse goes first). Once one has registered this difference, it is easy to distinguish who does what elsewhere. On the whole I prefer Quinichette’s playing, in part because it has a certain wit, which makes Rouse sound a little solemn and stolid. Still, Rouse produces some interesting solos, notably on ‘Knittin’’ and ‘This Can’t Be Love’. This album isn’t a tenor ‘battle’ (however factitious) in the manner of, say, numerous albums by Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt. But, even if there is nothing of the ‘cutting contest’ here, there is plenty to enjoy, and the distinctiveness of the two tenor ‘voices’ sustains one’s interest throughout, as does the work of pianists Wynton Kelly (there is a very characteristic solo on ‘This Can’t Be Love’) and Hank Jones (heard to advantage on ‘You’re Cheating Yourself’).

Fred Jackson is probably the least familiar name amongst these tenor saxophonists. The album reissued here carries a title which tells the listener what to expect – Hootin’ and Tootin’. Jackson worked with Little Richard from 1951-53; this album was made when Jackson’s regular work was with another R and B vocalist, Lloyd Price. Jackson was thoroughly grounded in the R and B tradition. As hard bop embraced elements of that tradition, so it became quite common for saxophonists from the R and B world to be given the opportunity to work with jazz musicians – this happened, for example, with David ‘Fathead’ Newman and King Curtis. In January 1961, Jackson played on a Blue Note recording, Face to Face, led by organist [Roosevelt] ‘Baby Face’ Willette – an album which benefitted from the presence of guitarist Grant Green; Jackson acquitted himself sufficiently well for Blue Note to offer him the chance to record an album of his own – the one reissued here. To make it, he brought into the studio three colleagues from the Lloyd Price band. So, rather, than the incorporation of an R and B player within a jazz context (when Prestige recorded The New Scene of King Curtis in 1960, they put him with cornetist Nat Adderley, pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Oliver Jackson, so that he had top-quality jazz support), Jackson was supported by less jazz-sophisticated musicians. Organist Earl Van Dyke was utterly competent within the R and B idiom, so much so that he later became the mainstay of the Funk Brothers, the house band which played on innumerable Motown records. But, as a jazz organist he is much inferior even to a relatively minor figure like Willette. The best I can say of Jackson’s album is that it is bluesy soul-jazz with the occasional nod to the language of hard bop, mixing uptempo blues with slower numbers, all swinging consistently. The tracks feature much longer solos than these musicians would have had the chance to play when supporting Price, but rather than merely exposing their limitations, the length serves to show that Jackson in particular, and to a lesser degree Van Dyke and Jones have some jazz ‘chops’. There is nothing really memorable here, and certainly nothing particularly distinctive or innovative. Yet, there is an attractive authenticity to the playing of the blues. Jackson made a second session for Blue Note, with the same musicians, plus bassist Sam Jones, in April 1962, but the tracks recorded then were not initially released (perhaps because Hootin’ “N” Tootin’ hadn’t sold well?). Jackson was, however, back in the recording studio for Blue Note in 1963 and 1964 in quartets led by organist Big John Patton (Along Came John and The Way I Feel). Jackson’s spell as a jazzman was effectively over, though the tracks recorded under his own name in April 1962 were added to a later CD reissue of Hootin’ “N” Tootin’ in, I think, 2009.

Don Wilkerson might seem, superficially, to be a similar case to Fred Jackson – an R and B tenor saxophonist flirting with jazz. Wilkerson (1932-1986) was born in Louisiana, but brought up in Houston. As a young man he played tours with figures such as the pianist and vocalist Amos Milburn and guitarist / singer T. Bone Walker, before spending two spells with Ray Charles in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His Texan upbringing was vital. It made him heir to a school of playing usually called ‘Texas tenor’, a tradition running through such figures as Arnett Cobb, Illinois Jacquet, Buddy Tate, David ‘Fathead’ Newman, King Curtis, John Hardee, Wilton Felder and Curtis Amy and perhaps traceable all the way back to Herschel Evans. In both R and B and jazz, such saxophonists played with a powerful tone and a forceful, direct delivery – the very opposite of, for example, the lightness and obliquity of Lester Young. Ted Gioa (in his History of Jazz, 2nd edition, 2011) characterizes the style as “blues-drenched”, marked by “gritty, soulful phrasing”, as being “an ever-present ingredient in the jazz and popular music of Texas”. It was, I think, Cannonball Adderley who said of the style that it had “a moan in the tone”, as Wilkerson certainly does. Indeed, it was on Adderley’s recommendation that Riverside made The Texas Twister, Wilkerson’s first jazz album. Sensibly, Wilkerson was recorded alongside experienced jazz musicians such as Barry Harris, Nat Adderley, Sam Jones and Billy Higgins. This means that he doesn’t, unlike Jackson, have to carry almost all the soloing weight. Nor, again unlike Jackson, was he allowed to record a programme made up entirely of his own compositions, so that the musical context is more varied. The result is a much better album than Hootin’ “N” Tootin’, on which standards like ‘Easy to Love’ and ‘Where or When’ ensure that Wilkerson can’t simply fall back on the R and B licks he had played so often. In the process a genuine ‘jazz’ sensibility is revealed, backed up and stimulated by the high-class musicianship around him. Not for the first time I am struck by my impression that Nat Adderley often plays better when not standing alongside his brother. (The session was produced by brother Julian, but he left his horn in its case). This is very definitely a jazz album, and a pretty good one too. Listen to CD2 straight through and there is an unmistakable sense of a falling away as Hootin’ “N” Tootin’ succeeds The Texas Twister. To listen to all four of Wilkerson’s albums – something I recommend – is to feel that here was a jazz talent which went largely unfulfilled.

Something of the same holds true for J.R. Monterose. The most succinct summary I know of Monterose’s career is that by Richard Cook and Brian Morton in The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD. I quote from the Fifth edition, 2000: “Hard-bop stylist, in thrall to few influences, rarely recorded and often forgotten now”. Born in Detroit but brought up in Utica (New York State) the full name of Monterose (1927-1993), was Frank Anthony Peter Vincent Monterose; the initials J.R. were merely a version of Jr. (‘Junior’). Largely self-taught as a saxophonist, Monterose seems always to have valued his independence. He initially worked with some territory dance bands in the late 1940s, and then with touring bands led by Henry Busse and Buddy Rich. However, he found working in big bands constricting and chose instead to spend some years working freelance in (as he put it) “little joints, but with good men”. He then gravitated towards New York City again, and in 1955 appeared on sessions led by vibraphone-player Teddy Charles, trumpeter Jon Eardley, British-born pianist Ralph Sharon (Charles Mingus was the bassist on this session) and trombonist Eddie Bert. Teddy Charles valued Monterose’s work and used him on several more sessions in 1956. In January of 1956, Charles Mingus chose to use Monterose on his great album Pithecanthropus Erectus. To my, and I suspect most, ears Monterose’s contribution to this recording sounds impressive, but he was unhappy with the experience (finding it difficult, one suspects, to subordinate his own personality and musical choices to Mingus’s control) and later spoke with very little enthusiasm of the recording. Still, at this stage in his career Monterose was keeping very impressive company. For a period in the mid 1950s he was a member of Kenny Doreham’s ‘Jazz prophets’, a group which unfortunately had a relatively brief life. Working with so many key figures on the New York Scene, both in the studios and in the clubs, doubtless encouraged Blue Note to give him the opportunity to record the eponymous album here reissued. (Oddly, Avid have omitted to tell us what year the record was made – 1956 – while informing us that it was recorded on October 21st!). On Monterose’s first recording under his own name, he was accompanied by a stellar line-up (only the multi-instrumentalist Ira Sullivan, here playing only trumpet, wouldn’t, I suppose, merit such an epithet, though he certainly acquits himself very well). J.R. Monterose is a powerful session, which swings hard, and on which Monterose displays a bitingly aggressive tone which seems to exude self-confidence, and is supported superbly, as one would expect from musicians of the calibre of Silver, Ware and Philly Joe Jones. If you don’t know/have this album already, and like hard-bop, I urge you to snap it up at Avid’s bargain price. It deserves (like J.R Monterose in general) to be much better-known than it is. Monterose’s playing Is not slavishly indebted to any other player, though he has certainly listened to many of the great tenor players, from Chu Berry and Lester Young to Sonny Rollins; but his voice remains his own. He made another album as a leader in 1959 – The Message, with pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Pete LaRoca, on which some of his best work can be heard. But from around the end of the 1950s he seems to have shunned the limelight, retreating from New York and becoming something of a musical itinerant, turning up from time to time, often in out-of-the-way places (in jazz terms), both in the USA and in Europe, sometimes making recordings for relatively obscure labels. Much of his potential seems, as a result, to have been frittered away, perhaps for reasons of personal temperament or perhaps, conceivably, because he was beset by the kind of ‘personal problems’ that affected so many of his contemporaries. Whatever the reason. the later paucity of recordings by Monterose makes albums like J.R. Monterose and The Message all the more valuable.

Glyn Pursglove