BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

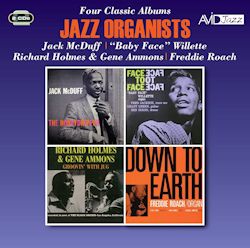

Jazz Organists Four Classic Albums |

[79:05 + 76:57]

CD1

1.Whap!

2.I Want A Little Girl

3.The Honeydripper

4.Dink's Blues

5.Mr. Lucky

6.Blues And Tonic

Jack McDuff, The Honeydripper

Jimmy Forrest (tenor sax), Jack McDuff (organ),

Grant Green (guitar), Ben Dixon (drums)

Rec. Hackensack (NJ), February 3 1961

7.Swingin’ At Sugar Ray’s

8.Goin’ Down

9.Whatever Lola Wants

10.Face To Face

11.Somethin’ Strange

12.High ’N Low

‘Baby Face’ Willette, Face to Face

Fred Jackson (tenor sax) ‘Baby Face’ Willette (organ)

Grant Green (guitar) Ben Dixon (drums)

Rec. Hackensack (NJ), January 3 1961

CD2

1.Happy Blues (Good Vibrations)

2.Willow Weep For Me

3.Juggin’ Around

4.Groovin’ With Jug

5.Morris the Minor

6.Hey You, What’s That?

Richard ‘Groove Holmes & Gene Ammons, Groovin’ With Jug

Gene Ammons (tenor Sax), Richard Holmes (organ),

Gene Edwards (guitar), Leroy Henderson (drums)

Tracks 1-5 Rec. live The Black Orchid, Los Angeles, August 5 1961

Track 6 Rec. Pacific Jazz Studios, Los Angeles, August 15 1961

7.De Bug

8.Ahm Miz

9.Lujon

10.Althea Soon

11.More Mileage

12.Lion Down

Percy France (tenor sax) Freddie Roach (organ),

Kenny Burrell (guitar), Clarence Johnston (drums)

Rec. Englewood Cliffs (NJ), August 23 1962

Fats Waller made some recordings on the pipe organ in the 1930s and a few later jazz musicians have also recorded on the pipe organ (including Keith Jarrett’s, Hymns /Spheres, recorded in a Benedictine Abbey in Germany, and Dick Hyman’s, Fats Waller’s Heavenly Jive, with Ruby Braff on cornet – not recorded in a Benedictine Abbey! Both, by a strange quirk, were recorded in 1976.

But the pipe organ is not naturally suited to jazz, for technical reasons and also presents problems of portability. The invention and manufacture of the Hammond electric organ, c.1935, made the organ a more common presence in the jazz context, used by, amongst others, Count Basie, Wild Bill Davis, Milt Buckner and Jackie Davis. The electric organ was used even more prominently on the Rhythm and Blues circuit. In the 1950s the Hammond B-3 organ was introduced and it was the example of Jimmy Smith, displaying the new instrument’s possibilities that led to an upsurge in the instrument’s use on the jazz scene. Smith dispensed with a bass player, playing the bass lines himself on the organ’s foot pedals. His first recording, made for Blue Note in 1956, was given the significant title of A New Sound-A New Star. Smith’s example was followed by numerous musicians including, in addition to the four organists heard on this 2 CD set, Don Patterson, Shirley Scott, Lou Bennett, Big John Patton, Jimmy McGriff, Johnny ‘Hammond’ Smith and Charles Earland.

The recordings re-issued here could hardly be called ‘Classic’ albums, if by that term one means recordings central to the history of recorded jazz (like, say, Kind of Blue, The Hot Fives, or Bill Evans’ Sunday at the Village Vanguard), i.e. albums ‘essential’ to any representative collection of jazz. But they are good examples of the fashion for organ- based soul-jazz which Smith initiated, and all four of them remain enjoyable listening (even if some of the most enduring interest resides in the playing of other members of the groups, rather than the organists themselves).

Jack McDuff (most often billed as ‘Brother’ Jack McDuff) could play funky blues as well as most contemporary organists, but could also produce some touches of subtlety and elegance (perhaps rather more than Smith himself). Here his quartet plays three numbers by McDuff (tracks 1, 4 and 6), plus Henry Mancini’s ‘Mr. Lucky’ and, from the early 1930s, ‘I Want A Little Girl’, by Billy Moll and Murray Mencher, an enduring tune recorded by artists as diverse as Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole and Eric Clapton, along with ‘The Honeydripper’, a 1945 hit for the R & B pianist and vocalist Joe Liggins. McDuff does his job perfectly competently, but I found my ears and mind being predominantly drawn to the playing of Jimmy Forrest, a saxophonist I have always thought to be seriously underrated; he plays impressively on most tracks of this album, rather stealing the show from the leader. Grant Green, in a relatively early recording (he was in his mid-twenties), already stands out in the subtlety of his approach, whether in a whole lot of brief fills or a sophisticated solo such as that on ‘I Want A Little Girl’. Tenor/organ quartets easily became formulaic, but the presence of Forrest and Green stops any tendency for McDuff and Dixon to settle for the merely routine – Forrest’s intense solo on the first track sets the standard for what follows.

‘Baby Face’ Willette – whose given name was Roosevelt – was the son of a father who was a minister and a mother who played the piano in church, so it is perhaps unsurprising that he proved at home in the gospel-influenced music that was one of the idioms of soul-jazz. As an organist he has a rather emphatic and aggressive manner. Although Face to Face is a studio recording, Willette sometimes sounds as though he is trying to quell a rowdy audience and get their attention. ‘Goin’ Down’ has a powerful solo by Jackson – better than most of his recorded work. ‘Whatever Lola Wants’ becomes a kind of bluesy mambo and is decidedly catchy – good juke box material in its day, I’d guess. ‘Face to Face’ is pure funk (if that isn’t an oxymoron too far) and is, again, a catchy performance. There’s more earthy blues on ‘Somethin’ Strange’ and on the closer, ‘High ’N Low’ which, though taken slowly, keeps a grip on the listener’s attention. Jackson, throughout, lacks Forrest’s varied invention and sometimes settles for repetitive honking. Green, though, once more has interesting things to say.

The combination of Richard ‘Groove’ Holmes (whose nickname was perhaps justified by his genuine ability to swing) and Gene Ammons is, predictably, successful. Ammons always thrived on a swinging, but basic blues-based accompaniment and Holmes provides that in spades. Ammons plays with a characteristically big sound throughout and his presence means that Holmes doesn’t do what he sometimes did and fall back on a few repeated motifs. The result is entertaining and engaging. The two ‘big’ names work well together, and each keeps the other at the top of his game. ‘Happy Blues’ sets the mood, ‘Hittin’ the Jug’ is a delightful slow blues, full of feeling, while ‘Juggin’ Around’ is something of a burn up; ‘Willow Weep for Me’ gets a heavily moody, late-night treatment. There is even better Ammons to be found elsewhere, but this must be amongst the recordings made under Holmes’ name. The relatively unfamiliar guitarist Gene Edwards acquits himself pretty well, though there seems to be some distortion of his sound.

Of the organists who ‘followed’ Smith, Freddie Roach was perhaps the subtlest, in musical terms. His playing was more varied in dynamics, more sophisticated in its range of colours than that of most of his contemporaries. Roach’s mother was a church organist and her son started playing the pipe organ at the age of eight. Later he played professionally with Cootie Williams, Lou Donaldson and others. He played on two Blue Note albums by Ike Quebec (Heavy Soul and It Might As Well Be Spring, both 1961). Evidently impressed, Alfred Lion gave Roach his own contract and he made five albums for the label, of which Down to Earth was the first. Later he recorded three albums for Prestige, in a more straightforwardly funky idiom than that of his Blue Note recordings. Listening to those later recordings, one wonders whether Roach’s heart was really in the music; did he feel the need to be more ‘commercial’? Or perhaps he felt under pressure to be so. In 1970 he walked away from music and apparently went to work in theatre and film. All six of the tunes on Down to Earth are by Roach. They are not, it has to be said, especially memorable but, given the date of the recording they are pleasantly free of the clichés of soul jazz. ‘Althea Soon’ is quite attractive and benefits from an interesting solo by Kenny Burrell. Percy Jackson is an undistinguished (and largely uninteresting) soloist. Later Blue Note albums by Roach were to feature tenor players such as Hank Mobley and Joe Henderson. On ‘De Bug’ Roach displays the gracefulness he could bring to the Hammond organ. The rapidity of his right hand gives pace ands air to his best work.

The ‘popular demand’ however, where jazz organ was concerned, was for a simpler funkiness – which Roach made some attempt to provide, though he met with little commercial success – his career was ended early and a genuine talent was lost to jazz, a talent which, without being startlingly original, was attractively distinctive. It was left, primarily, to Larry Young to evolve a post-Smith style of jazz organ.

Glyn Pursglove