BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

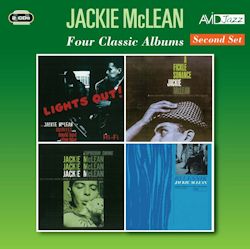

Jackie Mclean Four Classic Albums

|

CD1

Lights Out

Lights Out

Up

Lorraine

A Foggy Day

Kerplunk

Inding

Jackie McLean (alto sax) Donald Byrd (trumpet), Elmo Hope (piano),

Doug Watkins (bass) Arthur Taylor (drums)

rec. January 27 1956

A Fickle Sonance

Five Will Get You Ten

Subdued

Sundu

A Fickle Sonance

Enitnerrut (Turrentine)

Lost

Mclean (alto sax) Tommy Turrentine (trumpet), Sonny Clark (piano),

Butch Warren (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

rec. October 26 1961

CD2

Capuchin Swing

Francisco

Just For Now

Don’t Blame Me

Condition Blue

Capuchin Swing

On the Lion

Mclean (as) Blue Mitchell (trumpet), Walter Bishop Jr. (piano),

Paul Chambers (bass) Taylor (drums)

rec. April 17th 1960

Bluesnik

Bluesnik

Goin’ ‘Way Blues

Drew’s Blues

Cool Green

Blues Function

Torchin’

McLean (as) Freddie Hubbard (trumpet), Kenny Drew (piano),

Doug Watkins (bass), Pete La Roca (drums)

rec. January 8th 1961

I recently found myself in conversation with two of an increasingly rare species – undergraduates with an interest in jazz (very rare outside our Music Colleges, at any rate). These two – boyfriend and girlfriend – raised the name of Jackie McLean as an artist they listened to. I soon realized that to them McLean was an alto player who, playing from the 1960s onwards, embraced many of the stylistic innovations of free jazz, who played and recorded with bands made up of musicians a generation younger than himself and who (on his New and Old Gospel, 1967) had Ornette Coleman alongside him in a group that played two Coleman compositions. musically speaking and how ions.

The two knew little or nothing of where Mclean had come from, musically speaking, and how such an album represented a movement beyond the bop and hard-bop conventions with which McLean had grown up and within which he had established a considerable reputation.

McLean’s roots were very much in bebop; as a young man his friends and neighbours included Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell and Charlie Parker. He studied and practised with Powell. While still in High School he gigged with Sonny Rollins and Kenny Drew. He went on to work with Rollins, Mingus and Miles Davis. He also developed, in his early years as a professional, an addiction to heroin which cost him his cabaret card and, therefore, working opportunities in the clubs of New York. His playing, though he learned much from Parker, was marked by a distinctive, unorthodox tone (decidedly astringent) and a tendency to play slightly sharp, as well as an improvisatory manner in which urgent momentum was generally more important than harmonic sophistication: much of this is clearly in evidence in the four albums reissued here, as his deep-rooted feeling for the blues.

The earliest of the four recordings, Lights Out, is full of direct and intense work by McLean, with the bonus of the wonderful Elmo Hope at the piano. On A Fickle Sonance McLean’s work is audibly a little more mature and this album benefits from the presence of another fine pianist, Sonny Clark as well as some fiery work by trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, with Warren and Higgins proving themselves, as they so often did, to be a tight yet flexible rhythm section. This is hard bop of real quality.

So, too, is the music on Capuchin Swing (McLean kept a capuchin monkey as a pet). McLean was often content to blow on fairly basic material, but here a tune such as ‘Francisco’, which has an unconventional structure, brings out some fine work from him. The ‘head’ of ‘Francisco’ is 20 bars long, made up of a 12 bar blues and 8 further bars which are ‘Latin’ in nature. In solo the musicians play in terms of these ‘sections’, each at double its original length. Such a structure vivifies the conventions of Hard Bop, which McLean was soon to find constricting, as albums such as Let Freedom Ring (1963), One Step Beyond (1963) and Destination … Out! (1963) demonstrate.

Bluesnik , from 1962, is still recognizably in the Hard Bop mould, but in some respects, such as line and phrasing, McLean’s playing seems to owe at least as much to Coleman and Dolphy as to Parker. Freddie Hubbard also incorporates some freer elements in his solo work. But, above all, this album extends (and intensifies) that blues feeling which was always fundamental to McLean’s work. Again, he has chosen a fine rhythm section, not least in Pete La Roca and Doug Watkins.

This 2-CD set would, I think be both appreciated and somewhat surprising to the two undergraduates mentioned earlier. McLean followed a fascinating trajectory as an innovative traditionalist (or a tradition-minded innovator, if one prefers). Or, if you simply enjoy Hard Bop played well and, like me, no longer have the original LPs, do treat yourself to this fine collection.

Glyn Pursglove