BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

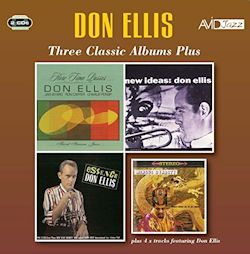

DON ELLIS Three Classic Albums Plus

|

CD1

How Time Passes

How Time Passes

Sallie

A Simplex One

Waste

Improvisational Suite #1

New Ideas

Natural H

Despair to Hope

Uh-Huh

Four And Three

Imitation

Solo

CD2

New Ideas

Cock and Bull

Tragedy

Essence

Johnny Come Lately

Slow Space

Ostinato

Donkey

Form

Angel Eyes

Irony

Lover

[4 tracks from Charles Mingus, Mingus Dynasty]

Slop

Things Ain’t What They Used To Be

Mood Indigo

Put Me In That Dungeon

How Time Passes :

Don Ellis (tpt), Jaki Byard (piano, alto sax), Ron Carter (bass)

Charlie Persip (d) rec NYC October 4-5 1960

New Ideas :

As above, plus Al Francis (vibes)

rec Englewood Cliffs (NJ) May 11 1961

Essence :

Ellis (tpt), Paul Bley (piano) Gary Peacock (bass)

Gene Stone / Nick Martinis (d)

rec Hollywood July 14 1962

[tracks from] Charles Mingus, Mingus Dynasty

Ellis (trumpet) Jimmy Knepper (trombone) John Handy (alto sax)

Booker Ervin (tenor sax) Roland Hanna (piano) Charles

Mingus (bass) Dannie Richmond (drums) Maurice Brown

& Seymour Barab (cellos) rec NYC November 13 1959

After obtaining a degree in composition from Boston University in 1956, Don Ellis began to work in a variety of big bands, including those of Charlie Barnet, Claude Thornhill, Woody Herman and Maynard Ferguson. Always a technically accomplished instrumentalist, once Ellis began to make albums under his own name, he demonstrated his restless desire for innovation and for the appropriation/assimilation of ideas and methods from other musical languages, including both modern classical music and Indian music (he later drew on rock, electronic music and Brazilian idioms too). In later years this sometimes resulted in music so eclectic that novelty could appear to be an end in and of itself. Whitney Balliett’s brief report on a performance at the 1968 Newport Festival sums up the effect, which could be exhilarating, but seem rather rootless and unfocused: “Don Ellis’s infallible nineteen-piece Los Angeles band closed the festival with a number in thirteen-four, a Country-and-Western in seven-four, an ingenious reworking of Charlie Parker’s ‘K.C. Blues’, and an electrophonic number that summoned up other galaxies”. The big band albums he made, from the second half of the 1960s onwards, show off Ellis’s skill (and ingenuity) as an arranger (my own favourite is Electric Bath, recorded in 1967), but the best representation of Ellis the trumpeter is to be found in his early small-group recordings, such as the three full albums included on this two-CD set from Avid.

By the time he recorded these albums California-born Ellis, by then based in New York, had experience of working with George Russell and was also taking on board ideas from figures such as Cage and Stockhausen. There is, though, still, a strong sense of the jazz tradition on all three albums, as evident in Ellis’s masterly playing on the Ellingtonian ‘Johnny Come Lately’, and his blues-flavoured work on Carla Bley’s ‘Donkey’. What was to be an enduring fascination with unusual and complex time signatures as well as in variations of tempo (both are punningly hinted at in the title ‘How Time Passes’) makes this music distinctive. In ‘Ostinato’, for example, passages in 5/8 and 7/8 are layered on top of a basic 4/4 rhythm. The lengthy ‘Improvisational Suite #1’ is based on twelve-tone rows (this reissue reproduces Gunther Schuller’s detailed analysis of the piece). None of this need alarm listeners who (like me!) are far from being experts in compositional theory. For the most part the music remains readily accessible and emotionally communicative. Ellis benefits from the presence and support of some well-chosen sidemen, musicians with a thorough grounding in the main stream of jazz tradition, but possessed of ears and minds open enough to want to ‘grow’ that tradition, musicians such as Jaki Byard, Paul Bley, Ron Carter and Gary Peacock. Bley and Peacock are consistently impressive in their contributions to Essence. According to Ellis’s own sleeve note to New Ideas, vibraphone player Al Francis was making his “debut”; I take this to mean that this was Francis’s first recording. His work is intelligently and unselfishly innovative. I wonder what happened to Francis? I can’t recall ever encountering him on record again.

I have some jazz-listening friends who were put off Ellis by the extravagances of some of his big-band records, but in at least two cases such friends have reassessed Ellis the trumpeter after I played them some of his small-group recordings. I urge other sceptics to repeat the experiment. I dare say some will still find Ellis too self-consciously experimental in places, but more would, I hope, find themselves acknowledging the quality of Ellis’s best work.

If I have one small niggle to make about this collection, it concerns the presence of the four tracks from Mingus Dynasty, tracks on which Ellis is present, but does not solo. All four tracks are, in themselves well-worth hearing, but don’t contribute much to an appreciation of Ellis. It would surely have been better to have given over some of the twenty minutes devoted to Mingus Dynasty to a few tracks from Ellis’s excellent 1961 album Out of Nowhere, a trio recording with Paul Bley and bassist Steve Swallow, largely devoted to some very original interpretations of jazz standards. A track such as the brilliant reading of ‘All the Things You Are’, for example, would make a much more coherent fit with the other three small-group albums. With that small reservation, this set is very warmly recommended.

Glyn Pursglove