BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

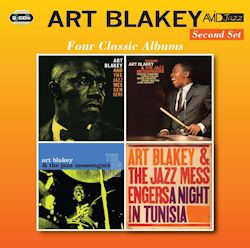

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Four Classic Albums (Second set) |

CD1

Moanin’

Moanin’

Are You Real

Along Came Betty

The Drum Thunder Suite

Blues March

Come Rain or Come shine

Lee Morgan (trumpet) Benny Golson (tenor sax), Bobby Timmons (piano),

Jymie Merritt (bass) Art Blakey (drums)

rec. October 30 1956

Mosaic

Mosaic

Down Under

Children of the Night

Arabia

Crisis

Freddie Hubbard (trumpet) Curtis Fuller (trombone), Wayne Sorter (tenor sax)

Cedar Walton (piano), Jymie Merritt (bass), Art Blakey (drums)

rec. October 2 1961

CD2

TheBig Beat

The Chess Players

Sakeena’s Vision

Politely

Dat Dere

Lester Left town

It’s Only A Paper Moon

Lee Morgan (trumpet) Wayne Shorter (tenor sax), Bobby Timmons (piano),

Jymie Merritt (bass) Art Blakey(drums)

rec. March 6 1960

A Night in Tunisia

A Night in Tunisia

Sincerely Diana

So Tired

Yama

Kozo’s Waltz

Lee Morgan (trumpet) Wayne Shorter (tenor sax), Bobby Timmons (piano),

Jymie Merritt (bass) Art Blakey(drums)

rec August 7 & 14 1960

Four more ‘Classic Albums’ from Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Avid already re-issued four other albums under the same title. To tell the truth, a blind man with a pin would stand a pretty good chance of picking out albums deserving of the epithet ‘classic’ from a discography of Blakey’s constantly evolving group. Certainly, these four albums are ‘classics’ of their kind. They are parts of the spine (and nervous system) of hard bop. If any one group defined – and promulgated the principles of that movement – it was Blakey and his Jazz Messengers. Not without reason has this band been referred to as an ‘academy’ or ‘university’ of modern jazz, given Blakey’s ability to spot talented musicians and ‘educate’ them musically within the Messengers. (see Alan Goldsher’s 2002 book Hard Bop Academy: The Sidemen of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers ). A selective list of the trumpeters who graduated from the Messengers will make the point: Kenny Dorham, Donald Byrd, Bill Hardman, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Valery Ponomarev, Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Wallace Roney, Philip Harper and Brian Lynch.

The four albums in this 2-CD set were recorded in the space of just three years, all for Blue Note. There is a fair degree of continuity in personnel across the four albums, Jymie Merritt plays bass (excellently) on all of them, pianist Bobby Timmons appears on three, as do trumpeter Lee Morgan and tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter.

The earliest of these albums opens with the Bobby Timmons’ composition ‘Moanin’’, a piece which borrows from gospel music, in terms of call and response patterns, and became something of an ‘anthem’ for the hard bop movement, played by musicians who wanted to declare their allegiance to the style. The Messengers continued to play the tune for some years after Timmons had left the band. Here, Morgan, Golson and the composer take two solo choruses each and Merritt is given one. Two other originals on the album, Golson’s ‘Blues March’ and ‘Along Came Betty’ also went on to find lasting places in the group’s book. Morgan who was, I think, here making his recorded debut with the Messengers, plays impressively on both, and Golson plays with an intensity he didn’t often display in bands under his own leadership. Blakey, unsurprisingly, gets an extended showpiece on ‘Drum Thunder Suite’, but his work as an ensemble drummer is, I think, more memorable than his solo work, on this album at least. This version of ‘Blues March’ is attractive, though some later performances by the Messengers packed more of a punch.

By the time The Big Beat was recorded in March 1960, Golson had departed (he did so in 1959, when he was replaced, briefly, by Hank Mobley who, in turn, was replaced by Wayne Shorter; Shorter had been with the Messengers for around six months at the time of this recording). Shorter, as Golson and Morgan had been, was later to be designated ‘music director’, though it is worth remembering that in an interview just a few months before his death in October 1990, Blakey told Francis Davis “I’m the real music director back there, I’m the one directing the traffic” (quoted in Davis, Jazz and its Discontents, 2004). Shorter provides three originals on The Big Beat, alongside one standard, another pseudo-gospel number by Timmons (‘Dat Dere’) and Bill Hardman’s minor blues ‘Politely’. The Big Beat has generally been amongst the most popular of Messengers’ albums, though I wouldn’t put it right at the top of the list myself; the limited inventiveness of Timmons’ playing is too evident and Shorter hadn’t yet completely found a way of reconciling his own individuality with the Blakey ‘essence’. But there are certainly good things here – not least in the work of Lee Morgan, full of creative joy and emotional substance. Yet ‘Dat Dere’ must have seemed somewhat formulaic even at the time, in its attempt to reproduce the success of ‘This Here’ and ‘Moanin’’; Timmons’ own solo doesn’t do much to redeem his composition, though those by Morgan and Shorter are considerably more satisfying. Of Shorter’s tunes, ‘Sakeena’s Vision’ works best. Its title refers to Blakey’s two-year-old daughter and Blakey pays tribute with a fine solo. Both Morgan and Shorter impress too. On ‘The Chess Players’ Morgan’s solo has lots of ‘soul’ and a weight of personal expression where Shorter’s is somewhat analytical. The third of Shorter’s compositions, ‘Lester Left Town’ is perhaps the most interesting as a tune, and makes an eloquent tribute to Pres. Shorter’s solo here is particularly cogent and lucid, while Morgan’s has flair and fire. ‘Politely’ works well, with Timmons sounding at home on this blues and the whole thing held together by Merritt, and by Blakey’s back-beat.

The next of these four albums, chronologically speaking, was A Night in Tunisia. As ever, Blakey’s ensemble drumming is both powerful and precise, providing repeated stimulation (one might be tempted to call it ‘provocation’) for the rest of the band. On the title track there are moments when it is hard to believe that only one drummer is present, as Blakey sustains a percussive storm through most of the track’s more than eleven minutes. The result is not, perhaps, a version of the tune one would want to listen to very often in quick succession, and its power is so remarkable that if one listens to the album in track order, it comes close to overshadowing everything that follows. One needs to guard against allowing that to happen, because several of the later tracks are also outstanding in their different ways. Shorter’s ‘Sincerely Diana’ is a rather quieter delight, with Shorter’s sinuous tenor strikingly impressive, and Morgan adding his more direct kind of passion. Listening to these four albums again has made realize afresh what a loss Morgan was when, at the age of 33 he was shot and killed by his common-law wife Helen Morgan. Timmons’ ‘So Tired’ mines his familiar blues territory, though in less hackneyed fashion than the pianist often did, and it draws some emotionally intense work from Shorter as well as from Morgan. But Timmons’ tune is a good deal less interesting than the two by Lee Morgan which close the album. Morgan was, at the time of writing the tunes, married to a Japanese woman and the titles of the two tunes (‘Yama’ and ‘Kozo’s Waltz’) reflect that association. ‘Yama’ means mountain and is also an abbreviation of his then wife’s maiden name ‘Yamamoto’ which means ‘Mountain-true’. In her sleeve-notes to the original issue of the album, Barbara J. Gardner tells the reader that “Loosely translated ‘kozo’ is a Japanese word roughly equivalent to our ‘kid’. It is the name which the Morgans have given to their pet poodle”. Both tunes, while having nothing very oriental about them are distinctive and attractive, rhythmically subtle, pieces. They have a charm and tenderness which one doesn’t always associate with Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. They are, in short, at the very opposite pole, stylistically speaking, from the album’s opening (and title-) track.

The final album here, Mosaic, brings with it three changes in personnel – with Freddie Hubbard now holding the trumpet chair, and Cedar Walton at the piano, and with trombonist Curtis Fuller added to the front line. This was, I believe, one of the finest of the Messengers’ line-ups (it can also be heard in top-class form on Buhaina’s Delight and the two volumes of Three Blind Mice). The presence of Fuller allows for greater complexity – such as three-part ensembles in the front line, Walton was also a more sophisticated and varied pianist than Timmons. While I wouldn’t want to claim that Hubbard was superior to Morgan, I think he did bring some distinctive qualities of his own. Both Walton and Hubbard were quick to contribute compositions to the group’s repertoire – ‘Mosaic’ is by Walton, while ‘Down Under’ and ‘Crisis’ are by Hubbard. ‘Children of the night’ is a particularly striking piece by Shorter and Fuller wrote ‘Arabia’. Walton’s ‘Mosaic’, with its modal elements and its unexpected changes of time signature, doesn’t immediately sound like Messengers material, but with Blakey at the back “directing the traffic” it goes with an impressive swing and is marked by some fiercely bright trumpet from Hubbard. The tune might. Perhaps, be taken as the announcement of an increased complexity in the band’s music. Shorter’s ‘Children of the Night’ offers further evidence of this new compositional complexity (and has a masterly solo by Shorter), as does Hubbard’s ‘Crisis’. ‘Children of the Night’ (a tune with which Shorter chose to open his 1995 album High Life, his first recording as a leader for some 7 years), with its complex chord changes and, its alternation of eight and twelve-bar phrases and its switchess of rhythm is a testing piece to play, but you wouldn’t think so from the fluent, yet dark intensity of this performance. ‘Crisis’ has a 56-bar chorus. Though less complex than these three compositions, Hubbard’s ‘Down Under’ is also constructed somewhat unusually. I quote from Leonard Feather’s original sleeve notes: “after the first 16 bars (eight piano, eight ensemble) [it] segues into an intriguing series of six-bar phrases”. Feather adds, rightly enough, that “despite this unusual construction, the improvisations in effect are based on the minor blues”. Indeed, the interest of the piece resides in precisely this conflation of a pretty basic and familiar jazz pattern with an unusual structure. Curtis Fuller takes perhaps his best solo of the album on this number. Connoisseurs of Blakey solos will want to hear (and re-hear) ‘Arabia’ – written by Fuller – where the master is heard to excellent effect. This is an album which, while it makes an immediate impact on first hearing, goes on to reveal new and interesting subtleties on every subsequent hearing. It is a ‘classic’; one of the very best of all the many recordings made by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers and, indeed, one of the most accomplished of all ‘hard bop’ recordings. It alone is more than worth the modest price at which this Avid reissue of four albums sells.

Glyn Pursglove