BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

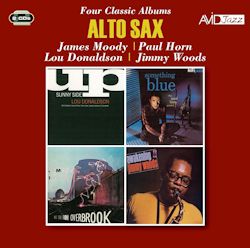

ALTO SAX Four Classic Albums

|

CD1

JAMES MOODY – Last Train From Overbrook

2.Don’t Worry About Me

3.Why Don’t You

4.What’s New

5.Tico Tico

6.There She Goes

7.All The Things You Are

8.Brother Yusef

9.Yvonne

10.The Moody One

James Moody (alto sax, tenor sax, flute), Fortunatus ‘Flip’ Ricard, Earl Turner, Sonny Cohn (trumpet), John Avant (trombone),Bill Adkins, Lenny Druss (alto sax), Vito Price, Sandy Mosse, Eddie Johnson (tenor sax), Pat Patrick (baritone sax), Floyd Morris / Junior Mance (piano), John Gray (guitar) Johnny Pate (bass, tuba, arranger), Isaac ‘Redd’ Holt (drums)

rec. Chicago, September 13-14 & 16 1958

PAUL HORN – Something Blue

11.Dun-Dunnee

12.Tall Polynesian

13.Mr. Bond

14.Frentz

15.Something Blue

16.Half and Half

Paul Horn (alto sax, flute, clarinet), Paul Moer (piano), Emil Richards (vibraphone), Jimmy Bond (bass), Billy Higgins (drums)

rec. Los Angeles, March, 1960

CD2

LOU DONALDSON- Sunny Side Up

*1.Blues for J.P.

*2.The Man I Love

**3.Politely

*4.It’s You Or No One

*5.The Truth

**6.Goose Grease

**7.Softly As In A Morning Sunshine

Lou Donaldson (alto sax), Bill Hardman (trumpet), Horace Parlan (piano),

*Layman Jackson (bass), ** Sam Jones (bass), Al Harewood (drums)

rec. **February 5, 1960; *February 28, 1960

JIMMY WOODS – Awakening!

8.Awakening

9.Circus

10.Not Yet

11.A New Twist

12.Love For Sale

13.Roma

14.Little Jim

15.Anticipation

Jimmy Woods (alto sax), Joe Gordon (trumpet, # 12,15), Martin Banks (trumpet,# 8,11-12),

Dick Whittington (piano, #10,13-14), Amos Trice (piano, #8-9,11-12,15) Jimmy Bond (bass, 8-9,11-12,15), Gary Peacock (bass, 10, 13-14) Milt Turner (drums)

rec. Los Angeles, September 13, 1961 (# 8-9,11-12, 15) & February 19, 1962 (#10,13,14).

Though all four albums on this 2-CD set are worth hearing (more than once), it has to be said that there are a couple of fairly eccentric choices, for a compilation called Alto Sax. Two of the four featured musicians are not primarily known as players of the alto sax – James Moody being far better known for his work as a tenorist and flautist; true, he did sometimes play the alto (though he does so on only one track of Last Train From Overbrook). Paul Horn’s fame – largely achieved outside jazz – was as a flautist. Lou Donaldson has already been given an Avid ‘Four Classic Albums) set to himself; indeed I reviewed it for MusicWeb ( http://www.musicweb-international.com/jazz/2017/Lou_Donaldson.htm )

So, to the music itself – the title of the fine album by James Moody, as well as being justified by the train effects on the title track, refers to a spell of a few months which Moody had voluntarily spent, prior to this recording, in the Overbrook Hospital in Essex County, New Jersey, where he was treated for problems of alcohol abuse. Having left Overbrook, ‘cured’, he travelled to Chicago to make this album. It very much takes the form of a fifteen-piece band supporting Moody as featured soloist, with the arrangements by bassist John Pate (these are somewhat akin to Quincy Jones’ big band writing of the period). Incidentally, the personnel listing provided by Avid doesn’t identify the tuba player who is clearly audible on ‘Tico Tico’; since Pate occasionally played that instrument, I have amended the personnel list accordingly on the assumption that he did so on this occasion.

Moody is in excellent form throughout, whichever of his three instruments he is playing, most notably his work – on flute – on ‘There She Goes’, ‘All The Things You Are’ and ‘Brother Yusef’ (presumably a dedication to Yusef Lateef); his tenor work on ‘Last Train From Overbrook’ is also top quality . The only track on which he plays (impressively) alto sax is ‘Why Don’t You’. There is a warm, happy feeling to most of the music, Moody clearly feeling pleased to have left some problems behind him; as always is solos are richly emotional.

James Moody appears to have had relatively little in the way of formal musical training, unless one counts his time as a member of a “negro band” in the US Army, c.1943-46. Paul Horn, by way of contrast, having begun to play the piano at the age of four, before taking up flute, clarinet and saxophone, went on to earn a Bachelor’s degree in music from the Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio and a Master’s degree at the Manhattan School of Music. After settling in Los Angeles he worked with Chico Hamilton and as a session musician. Though often appearing, in his early years as a professional, in jazz contexts he seems always to be fretting at the limitations of such contexts. So, on album such as Something Blue, one finds him, unattracted by the idioms of hard bop, seeking to create alternatives. He was a self-conscious ‘experimenter’, attracted by what might loosely be called ‘third-stream music’, fusing elements from the classical and jazz worlds. He went on, after his ‘jazz years’ (to quote the title of a compilation of his recordings made between 1961 and 1963) to explore jazz’s connections with the musical languages of other cultures. Eventually this brought him to the making of ‘new age’ and world fusion’ albums such as Paul Horn in India (1967),Inside the Taj Mahal (1969), Visions (1974) and Altura Do Sol (1975).

Here, on Something Blue he is playing, for lack of a better term, ‘chamber jazz’. The music is, for the most part, very intricate and tightly constructed, the themes often being of unexpected bar-lengths. I suspect that died-in-the-wool lovers of jazz will wish that Horn, who composed four of the themes (Richards and Moer also wrote one each) had left more space for the soloists to ‘blow’ with real passion. That was my initial reaction, but repeated hearings have tempered that view somewhat, and the music has rather grown on me. Certainly I have found myself admiring the way in which the musicians negotiate the intricacies of Horn’s ‘Mr. Bond’, for example. Music constructed with this complexity (much of it detailed in the album sleeve note by Gene Lees) makes an interesting change from the blowing sessions so common in much of the jazz contemporary with it. And there are passages, as on ‘Mr. Bond’ and ‘Half and Half’, when Horn does play his alto sax in a manner that has the real ‘cry’ of jazz within it. There is some delightful clarinet on ‘Something Blue’ and plenty of fine work on the flute elsewhere. Both Paul Moer and (especially) Emil Richards make significant contributions – though both made better jazz records elsewhere. Jimmy Bond is a tower of subtle strength (and solos well on ‘Mr. Bond’); though this is not the kind of musical context in which he was normally heard, Billy Higgins’ work at the drums is exemplary.

Hard bop is certainly the idiom governing Sunny Side Up. Donaldson was never an innovative musician, but he drew, with conviction, on the whole tradition of jazz from the swing era onwards – on ballads one is aware of a debt to Johnny Hodges, on blues he owes much both to Charlie Parker and to saxophonists from the R & B tradition. Donaldson frequently recorded as the only horn in a quartet, but is frequently at his best when a second horn is present to stimulate and provoke, as it were. The consistently underrated trumpeter Bill Hardman plays that role on Sunny Side Up, and in Horace Parlan the group has a pianist well-suited to Donaldson’s musical personality, so the album, not surprisingly, is thoroughly entertaining and engaging. Highlights include Gershwin’s ‘The Man I Love’, taken faster than usual, with Donaldson full of ideas in his solo and Hardman and Parlan also on very good form; ‘The Truth’, a Donaldson composition, draws on both the blues and the gospel/spiritual tradition – Donaldson’s solo is intense and vocalized, Hardman’s full of fire and vigour, while Parlan reinvents both traditions in distinctive fashion. Until he got tempted by pop and rock material, Donaldson was a consistent performer on record (chiefly for Blue Note, as on this album) from about 1957 to 1963. None of his Blue Note albums was poor, even if none of them was an out-and-out masterpiece. Sunny Side Up is amongst the best of them.

Jimmy Woods, about whom very little is known biographically, and who was very little recorded, is an intriguing figure musically. Reference books give 1934 as the year of his birth; he made a few recordings between 1960 and 1966, but then seemed to disappear from sight completely. He made two albums as a leader, Awakening! and Conflict (1963) - on which the musicians under his leadership included Andrew Hill, Harold Land and Elvin Jones!; he appeared on albums by Joe Gordon, Teddy Edwards, Chico Hamilton and Gerald Wilson. In the sleeve notes he wrote for the original issue of Awakening! Nat Hentoff characterized Woods’ sound and style very perceptively, observing that “the qualities most immediately evident in Woods’ playing are his passionate, penetrating sound and speech-like phrasing; fiercely secure sense of swing; and an empirical commitment to freedom that leads him into a new way of expanding the jazz language”. He is also blessed, in Hentoff’s words, with a strong “built in feeling for cohesiveness”.

These qualities are evident in abundance on Awakening! Woods thoroughly outshines the two trumpeters on the album, who sound rather tame and ‘proper’ by comparison. Indeed, almost all this best on the album is to be found in Wood’s own playing, as in his solos on ‘Not Yet’ and ‘Circus’ – passionate and exploratory but fully controlled and coherent; or his rhapsodic unaccompanied opening to ‘Love for Sale’, for example. ‘Roma’ is a dedication to the saxophonist’s wife Romanita – full of love’s joys and pains, of all the struggles of the heart. The album closes with the excellent ‘Antipation’ – Hentoff says of it (in words that now have a sad irony about them) that is a fitting conclusion since “it presages an important career”. Ironically, of course, Woods was soon to disappear and little more was to be heard from him after this album. All the more reason to value what we have, which still retains its impact and freshness.

.

Glyn Pursglove