DVD Film Review

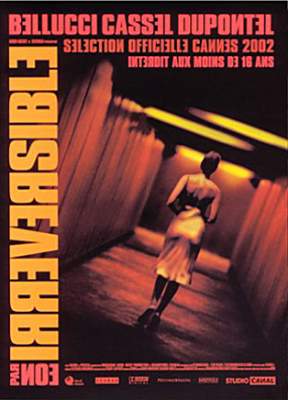

Irreversible (2002)

Dir, Gustav Noé

Music composed and performed by Thomas Bangalter (+ Mahler Symphony No.9 and Beethoven Symphony No.7)

Studio Canal, DVD 9, Format 2:35, colour, 99 minutes, French language (no subtitles)

Available from Amazon (France) as a boxed set containing Irreversible (plus soundtrack) and Seul Contre Tous

Gustav Noé’s art-house revenge thriller, Irreversible, is as searing a film as one is likely to legally see (especially in censored Britain). Taking European cinema one step closer to the films of Billy Tang (especially his indescribably powerful Red to Kill) and Katsuya Matsumara’s All Night Long series it is a 90 minute assault on the senses that does, and should, leave one consciously thinking about it long after it has ended. Uncritically, it has been dismissed as nothing more than this director’s attempt to shock his audience with graphic violence that serves no or little purpose, a film which according to Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard ‘contributes to the terminal state of individual helplessness’; critically, it should perhaps be viewed as a twenty-first-century attempt to cinematograph credulous events in a Jacobean, even Senecan, theatrical style. Irreversible owes as much to plays such as Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus and Seneca’s Thyestes as it does to any exploitative film of the last 30 years. Moreover, place, in a dramatic sense, is as important to this film as the events themselves – whether it be in the cavernous setting of the Rectum Club, where the ‘revenge’ is exacted, or in the subterranean, dimly-lit subway where the act that precipitates the ‘revenge’ is carried out.

The revenge is for the rape of Alex (an astonishing performance by Monica Bellucci) and its nine minutes are harrowing to watch. Perhaps because Noé doesn’t sensationalise it – and especially doesn’t eroticise it – it has escaped the scythe of the censors. Filmed head on, and at almost ground level, it has an unmistakable edge to it as we are forced to look at events face on. But it is Noé’s persistent association of sex and violence as somehow inter-connected that gives the scene its power – her face is pummelled into the concrete afterwards, less as an after thought, more as an orgasmic climax to the rape itself. Similarly, it is at the S & M Rectum Club – with its scenes of fisting, whether implied or actual, or where the search for pain is seen as an extension of sex – that the brutal murder by Pierre (Albert Dupontel) takes place. An arm is wrenched upwards and literally cracks apart, and a head is smashed to pulp with the base of a fire extinguisher until it caves in and becomes nothing more than a sea of flesh and bone – almost dripping across the floor like melted, blood-red candle wax. It is enormously powerful - and would be to most people inured to the 70’s or 80’s screen violence of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, Ruggiero Deodata’s House on the Edge of the Park or Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left, films which Noé’s is, if not a grandchild of, then certainly a godson of. But Noé adds something even more disturbing to his revenge scene: unable to distinguish between the reality of what they are seeing, and the onanistic sexual fantasies that have brought them there in the first place, a series of onlookers see the played out murder for what it isn’t: sex. It is this confusion of values which places Noé’s film above the norm.

Noé’s way with Irreversible, as its title suggests, is to film the action in reverse (even going so far as to opening the film with the closing credits). It is not a new concept – Christopher Nolan having done it only a couple of years ago with Memento. Thus, it starts in darkness and bleakness and ends in light and happiness. It starts with sex being brutalised and ends with sex being almost sanitised. It starts with the gloom and finality of Mahler’s last completed symphony and ends with the triumph and optimism of Beethoven’s Seventh.

Despite the excellent, crisp quality of Studio Canal’s DVD transfer the film opens up more vividly on the big screen, despite its obvious claustrophobia which might have made it more suitable to the limitations of television (it is also remarkable how little of the film is actually filmed in the open). The visual problem with the DVD is down to Noé’s technique which tends to film sequences in a fractious, kaleidoscopic way. Whirling cameras, placing images sideways or upside down, and often against a grainy darkness where the tenebrous overwhelms the brightness, give us glimpses of action rather than the whole of it. He lingers on images only momentarily, or, as in the case of the rape, lingers on them for what seems like an eternity deviating very little from his aim of making the action macroscopic with minimal panoramic effect.

Where this film differs from its equally controversial predecessors is in its use of music. Whereas Craven & Co used contemporary pop music to add to the triteness of the unfolding horror of their films, Noé engaged the services of Thomas Bangalter.

One half of the group Daft Punk, and one of the most gifted house producers around today, his soundtrack owes more to standard horror fare than one might have imagined. Keeping to the context of the film it is a pounding, scabrous composition which begins with slicing bass drum beats and follows with an echoing snare beat. Using some of Mahler’s most nihilistic music – the close of the Ninth symphony – overlapped with humming electronic effects, it brings the film closer in its dark, opening minutes to an apocalyptic nightmare than might otherwise have been the case. More Berg than Brangalter one might be tempted to write; more Wozzeck than Irreversible.

The pumping track for Rectum uses whaling sirens over and over again – both as an impending warning for the unfolding events and as a working image for the lack of emotiveness which infects the club like a disease. They drown out, then reappear, their intensity gathering momentum until the face-smashing reaches its gritty climax. Ominous organ chords, or a distant harpsichord, are applied as much as the submerging of a voice under twenty feet of water. Atonal guitar chords and a persistent electronic buzz are merged. It is by no means a classic score, and certainly not thematic in any way, but it does its job more than adequately.

The DVD includes a perceptive commentary from the director – even if his brutal, somewhat clinical methodology might leave some gasping. There is also a 16-page booklet which includes two pages of press quotes. Unsurprisingly, not one British newspaper is quoted. The only disadvantage of this edition of the film is that it is in French only with no subtitles at all. Whilst that is not necessarily a problem for viewing the film itself (which could so easily have been composed without any dialogue, and at times passes through bleeding chunks without any) it obviously is if you want to hear the director’s commentary and your French is limited. Yet, this is an uncut version of the film – and that is unlikely to be the case when it is released in the UK – so for completists it is an essential purchase.

Irreversible is a film which has no middle ground. You will either like it or you won’t. But, whatever your feelings it will leave an impression and a lasting one.

Marc Bridle

Editor's note: Irreversible was, perhaps surprisingly, passed uncut by the BBFC for UK cinema showing. As of today - 10 March 2003 - no decision has been taken regarding any possible DVD / video version. To check for any future decision visit http://www.bbfc.co.uk/

Return to Index