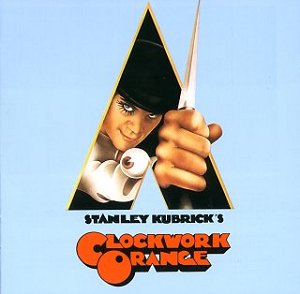

Collection: Music for Stanley Kubrick's Clockwork

Orange  WARNER

BROS. 7599-27256-2 [46:23]

WARNER

BROS. 7599-27256-2 [46:23]

Music, in some cases electronically adapted and/or abridged

from orchestral recordings, from Purcell (funeral music for Queen Mary),

Rossini (The Thieving Magpie and William Tell overtures), Beethoven

(Symphony No.9), Elgar (Pomp and Circumstance Marches No.1 &

IV). Also including Overture to the Sun by Terry Tucker. Electronic

music by Walter Carlos and Rachel Elkind. Songs: I Want to Marry a Lighthouse

Keeper written and performed by Erika Eigen, Singin' in the Rain,

composed by Freed and Brown, performed by Gene Kelly.

Now those of us under 44 finally have a chance to see A

Clockwork Orange (non-UK readers may be amazed to learn that the film

has been unavailable, at its director's insistence, in its country of original

for over a quarter of a century). Those older than that can see it again.

We can finally see what all the fuss was about, and more importantly for

our purposes here, attempt to make some sense of the soundtrack album. I

should note that the album reviewed here is the 15 track OST, not to be confused

with the 10 track album, on the cover of which a very threatening knife is

replaced with a glass of milk (threatening by implication only), but which

includes the complete 13 minute version of 'Timesteps', here cut to 4 minutes.

(You might wish it had been cut further - techno probably begins here).

The film is a flawed masterpiece, and one of the flaws concerns

the use of music, specifically classical music. After the brilliant use of

classical music in his previous foray into science-fiction, 2001: A Space

Odyssey (1968), Stanley Kubrick decided to cover large parts of each

of his following five films with classical extracts, almost entirely at the

expense of any original score. No composer is credited on the cover, and

you have to look inside the booklet to find the name Walter Carlos - later

the Wendy Carlos who would score Kubrick's The Shinning (1980), and

the proto-Matrix SF of Tron (1982). Carlos was a composer of

electronic music who played a large part in the development of the Moog

synthesiser, and achieved enormous commercial success in the late 60's with

the album Switched on Bach. Though largely forgotten today, this was

an incredibly popular LP, the first electronic music to find mainstream

acceptance, the forerunner of the 70's synth/prog rock of Tangerine Dream

and Jean Michel-Jarre, and ultimately, of the hellish clockwork cacophony

which today passes for popular music.

But why do I think the use of music is one of the flaws of

A Clockwork Orange?

(This is no place for a detailed synopsis: suffice to say that

the film is near future SF, that in a dystopian Britain a teenage gang run

on a riot of drug-fuelled sex and 'ultra-violence' until their leader, Alex,

is imprisoned for murder and brainwashed into conformity.) The Alex of Anthony

Burgess' source novel loved the music of Beethoven, and this love is kept

in the film as the one signifier of Alex's buried humanity: Burgess himself

wrote symphonies as well as novels, though recordings are hard to come by.

The film features a mixture of straight extracts from Beethoven and other

classical composers, plus electronic versions of other classical themes created

and performed by Walter Carlos. Presumably the intent is to create a futuristic

ambience, but nothing dates more quickly than last year's future, except

perhaps electronic music. Somehow, combined with the very 70's look of the

film, the music has dated A Clockwork Orange while 2001: A Space

Odyssey remains astonishing impervious to the hand of time.

Anthony Burgess has explained the rather baffling title, which

itself could have been the perfect name for a 70's rock band (think of Deep

Purple, Pink Floyd, Tangerine Dream) as symbolising something sweet, good

and life-giving, which has become bitter, lifeless and mechanical. Thus we

might accept the electronic-classical soundtrack as a realisation of this

idea, and to some extent it does work. The film opens with an electronic

setting of part of Purcell's music for the funeral of Queen Mary - listed

as 'Title Music from A Clockwork Orange' on the cover, and this is indeed

portentously chilling in it's synthesised grandeur. It sets the scene well,

and makes a strong opener to the disc.

However, the flaw I refer to runs much deeper: the synthesised

versions of Beethoven make no sense in terms of the purpose of the film.

In a key sequence in which Alex is brainwashed into feeling sick at the thought

of violence or sex, the film footage used to condition him is accompanied

by Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. The whole point of the brainwashing is to

make Alex feel as bad as possible, yet Beethoven's Ninth is generally considered

to be one of the most uplifting works in the classical canon. Thus its use

in this context simply makes no sense, playing as crassly pragmatic plotting,

engendering sympathy for Alex because afterwards he can no longer bear to

listen to his favourite music: his one connection with higher human values,

taken from him and corrupted.

Later, a writer by the name of Mr Alexander, having discovered

Alex is responsible for his disabling injuries and, indirectly, for the death

of his wife, tortures Alex with a recording of Beethoven's 9th.

With wild implausibility Mr Alexander plays Alex the same electronic version

of Beethoven which accompanied the mind-control film. Surely he would have

a recording of the original? No one in their right mind would buy the electronic

version featured here for pleasure, and surely it is far to improbable

a coincidence for the cultured writer to chose to use this version over the

real thing? Thus, on a level of pure plot, key musical ideas in the film

simply do not work. Translated to CD, the disc is a bizarre mixture of orchestral

extracts and electronic reworkings which makes for a uniquely alienating

experience. If the idea is to put one off listening to Beethoven, then it

works!

Rounding the disc off, Gene Kelly's incomparably wonderful

performance of 'Singin' in the Rain' seems even more incongruous than does

Alex's own shocking use of the song in the film itself. This is sweetness

turned sour indeed, and I for one would sooner associate the song with it's

50's context rather than it's 70's corruption. Listening to the album is

a surreal experience, from the mock vaudeville of 'I Want to Marry a Lighthouse

Keeper', via Rossini and Elgar, the strange electronic soundscape of 'Timesteps',

mutant Beethoven and innocent Kelly, it is as diverse, iconoclastic and

uncomfortable as the film itself. The sound quality is also inevitably variable,

with the orchestral recordings sounding better than the electronic ones.

Is it any good? is a question which seems terrible old-fashioned and irrelevant

here, but it is a useful document of an important film.

Reviewer

Gary. S. Dalkin

- as

a coherent and enjoyable musical experience

- as

a coherent and enjoyable musical experience

- as

a document of the film

- as

a document of the film