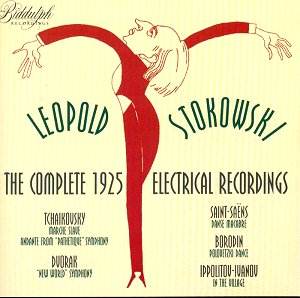

Stokowski first recorded in 1917 but technological

advances in the early 1920s meant his attitude to the acoustical

system had somewhat softened by the time that electrical recording

became a commercial reality. This disc collates an eight-month

period of recording in 1925, all electrically recorded, and all

bearing the mark of practical bet-hedging with regard to the properties

of the new method. As was fairly common practice for a few years

the bass line was reinforced; collectors are well used to the

double bass line being reinforced by tubas but Edward Johnson

in his elegantly candid sleeve notes quotes the Victor session

sheets in their deposition of the orchestra – no double basses

at all in the Borodin and Saint-Saëns, instead, amazingly,

a bass saxophone substitute (had Victor learned from their brass

and jazz recordings that the bass saxophone could profitably thicken

the orchestral texture?) In addition the timpani here was replaced

by a double bassoon. The compromises inherent are noticeable throughout

the disc and therefore this can’t realistically be said to be

a genuinely embryonic Philadelphia sound on disc, not least because

the string complement was drastically reduced pretty much in accordance

with proto-acoustic recording balances. Still, as a slice of technology

in action it’s most revealing and given that it’s Stokowski on

the rostrum never without interest.

The good news is that Biddulph have used fine

sounding Victors and Mark Obert-Thorn has transferred them without

fuss. In the Saint-Saëns violin fanciers can crane to hear

the long time concertmaster of the orchestra, the stentorianly

named Thaddeus Rich, who otherwise only recorded four 78 sides

for Okeh. The Borodin is an abridgement – orchestra only – from

the last of the Polovtsian Dances. This and the Ippolitov-Ivanov

were of course staples of Stokowski’s performing career – though

the latter was only returned to on disc in 1947 with the NYPSO.

The colouristic and exotic qualities of the music are obviously

rendered problematic by the orchestral limitations

and by the rather dull sounding recording. The strings have a

chance to show their flexibility and weight in the Tchaikovsky,

even if dogged by brass bass line impedimenta. The meat of the

disc is the December 1925 recording of the Dvořák New World,

a work Stokowski recorded six times in total. The relatively unsatisfactory

nature of the recording and the rapidity with which studio engineers

gained a relative degree of mastery over it necessitated a remake

almost immediately in 1927. The other recordings were again in

Philadelphia in 1934, the All-American Symphony in 1940, His Symphony

in 1947 and finally nearly thirty years later in London with the

New Philharmonia. In 1925 there are powerful portamenti, expressive

diminuendos, idiosyncratic touches and a strongly etched personality

controlling the music making. But the recording all too faithfully

picks up the lugubriously heavy substitute bass instruments –

the counterpoint of filigree strings and stygian tubas was a little

too much even for me, and I’m a notorious admirer of the acoustic

era Stroh violin (the one that attached a mini horn to the fiddle

to direct the sound). I’d stick with Stokowski’s 1927 or 1934

Philadelphia recordings.

Still, a rather fascinating slice of Stokowski’s

musical life on record, preserved in excellent sound given the

inherent limitations of poor acoustic venues and compromised orchestral

balances. I’m glad I’ve heard these early electrics.

Jonathan Woolf