Over the last decade or so there has been increasing

interest in the music of Alexander Zemlinsky, with a number of

recordings appearing - particularly of his Lyric Symphony.

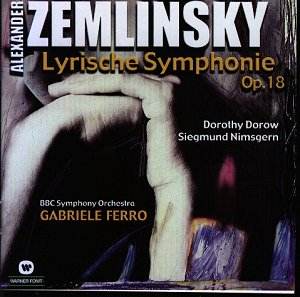

In fact this Warner Fonit reissue(?) of a 1978 BBC Symphony Orchestra

performance will soon face competition from a shortly to be released

Chandos recording.

Zemlinsky was more often known for his friendship

with Schoenberg (he married Zemlinsky’s sister) and as one of

the teachers of Korngold. His talent was admired and encouraged

by Mahler. In fact Zemlinsky’s Lyric Symphony strongly

resembles Mahler’s Song of the Earth. The Lyric Symphony

uses mystical poetry (by Rabindranath Tagore) of the East speaking

of dreamlike recollections of love.

The Warner Fonit recording of Zemlinsky’s Lyric

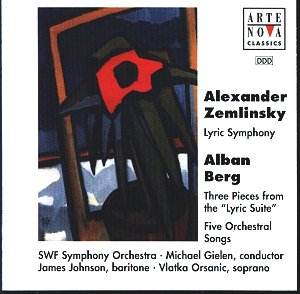

Symphony faces stiff opposition from the outstanding bargain

Arte Nova album that also includes the Berg pieces for good measure.

The opening song for baritone who is "athirst for faraway

things" and romantic adventure, employs huge orchestral resources

that Michael Gielen unleashes with ferocity and passion in a reading

that is more intense and faster than Ferro’s although the BBC

Symphony Orchestra’s response is not low on voltage either. The

Arte Nova sound has the edge too. Of the two baritones, both with

attractively arresting timbres, Nimsgern is more subtly expressive

and traces a more persuasive and sinuous vocal line.

The second song has a besotted young girl trying

to attract the attention of a prince as he passes beneath her

window. Gielen captures all her dreaming and yearning and then

despair as the prince passes on oblivious of her attentions, in

a glittering, voluptuous then crushing evocation as the prince’s

chariot drives over the jewel she had thrown in his path. In the

early section, Ferro’s recording is dreamier and more languid

as the girl ecstatically prepares herself and awaits the approach

of the prince. Dorothy Dorrow has a lyric soprano’s sweetness

suitable for the innocence of a young girl impossibly in love

while a deeper timbred Vlatka Orsanic is more volcanic in Gielen’s

more urgent pacing and more dramatic approach. But again Ferro

excites strongly too as the prince’s chariot unheedingly rushes

by.

Zemlinsky’s third song has the baritone dreaming

of his beloved and reflecting, "You are the evening cloud

floating in the sky of my dreams." The music very Mahler-like

here, yet not unlike Richard Strauss and Korngold too, is a perfumed,

floating sensuality as Ferro dallies over 7’:14" while Gielen

presses forward in 5’:27" allowing Johnson to be more persuasively

passionate, and opulent. The fourth song, a nocturne beginning

with a lovely violin solo sounds a note of sadness as the soprano

sighs, "Speak to me, my love!...I will clasp your head to

my bosom…the night will pale…The day will dawn. We shall look

at each other’s eyes and go on our different paths…" Zemlinsky

weaves orchestra magic here evoking a still, sylvan scene yet

with slightly disturbing spectral ripples. The soprano line is

beautifully merged into the instrumental fabric. One is reminded

not only of Mahler but also the nocturnes of Respighi and Korngold.

Ferro’s slower reading (by some 90 seconds) accentuates the sweet

despair more deeply while Gielen opts for a more romantic approach;

both sopranos are most persuasive.

In strong contrast, the fifth song has the baritone

anxious to break the silken bonds of love, "Free me from

the bonds of your sweetness … free me from your spells and give

me back the manhood to offer you my freed heart." The music

is brutal as the baritone is impatient to be free. Both conductors

compel the music forward in just over 1:50 with both baritones

terse and strident. Just as harsh is the soprano’s vindictive

response that is the sixth song. Both sopranos are viperish as

they scornfully dismiss their fickle lovers and their mounting

fury erupts spectacularly, especially by Gielen. The final song

with the baritone, more conciliatory, returns to the mood of the

first with "Peace, my heart … let love melt into memory and

pain into songs…O Beautiful End … I bow to you and hold up my

lamp to light you on your way." Nimsgern and Ferro are most

affecting while Gielen in the closing pages more strongly implying

that the lover is also anticipating fresh conquests.

Here I must complain about the very limited documentation

for both releases. The Warner Fonit album has detailed erudite

notes on Zemlinsky and his Lyric Symphony but includes

texts of the songs only in German and Italian. The Arte Nova release

has no song texts at all and the notes are poor and cursory. A

third, mid-priced recording of Zemlinsky’s Lyric Symphony

again with Michael Gielen conducting, this time, the BBC Symphony

Orchestra with Elisabeth Söderström and Thomas Allen

(with the same composer’s Six Maeterlinck Songs) released

on BBC Radio Classics in 1996 also leaves out the texts. It seems

that only full priced recordings of the Lyric Symphony have texts.

These are serious omissions and false economies by recording companies

– they only serve to frustrate and anger customers who really

need the texts to appreciate Zemlinsky’s achievement.

Gielen’s readings of the Alban Berg pieces included

on the Arte Nova recording are equally persuasive. The Lyric

Suite pieces, after the Zemlinsky composition, are colourful

and lyrical; experimenting with twelve-tone technique and frequently,

in Gielen’s Andante amoroso, and in the tremolandi and

pizzicatos of the Allegro misterioso, I was reminded of

Bernard Herrmann’s musical language for Hitchcock’s Psycho

and Vertigo. The oddly named Five Orchestral Songs after

postcard texts is more experimental and abrasive. Described

as a "subtly constructed work which invokes a doomsday atmosphere

by means of extreme drama" it pitches a lyrical soprano line

against a grotesque or violent or coldly remote musical landscape.

Although the newer Warner Fonit recording of

the Zemlinsky Lyric Symphony has much to recommend it including

two impressively expressive soloists, I marginally prefer the

dramatic power of Gielen’s Arte Nova recording in splendidly vivid

sound.

Ian Lace

![]() Dorothy Dorow (soprano)

and Siegmund Nimsgern (baritone)

Dorothy Dorow (soprano)

and Siegmund Nimsgern (baritone) ![]() WARNER FONIT 0927 43405-2

[48:01]

WARNER FONIT 0927 43405-2

[48:01]

![]() Vlatka Orsanic (soprano)

and James Johnson (baritone)

Vlatka Orsanic (soprano)

and James Johnson (baritone) ![]() ARTE NOVA 74321 27768

2 [66:07]

ARTE NOVA 74321 27768

2 [66:07]