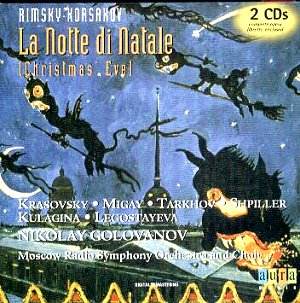

Composed immediately before Sadko, Christmas Eve (Noch’

pered Rozhdestvom) was based on the Gogol story that Tchaikovsky

had used for Vakula the Smith (Cherevichki). For all the charm

and brimstone, for all the lush orchestration and the stentorian devilish

rants, Christmas Eve succeeds mainly in demonstrating the relative limitations

implicit in the musico-scenic fantasies by which Rimsky was so greatly

taken. Following May Night, Snow Maiden and Mlada

Rimsky thought to complete the "Solar Cycle" with Christmas

Eve but its composition in 1894-95 overlapped with the beginnings

of interest in Sadko, a project that seemingly absorbed him far

more. Indeed the St Petersburg première of Christmas Eve was

boycotted by Rimsky, furious that the royal family had insisted on foisting

changes on it. Its reputation has scarcely recovered but if anyone was

going to breathe life into it Golovanov was the man. Recorded in 1947

with a strong cast this Lyrica double (from the Aura stable) comes with

a number of limitations for Anglophone, indeed non-Italian speakers

– there are no notes whatsoever and the booklet consists merely of an

Italian libretto. It’s as well to detail these potential bars to enjoyment

at the outset.

In the Introduction we are introduced to Rimsky’s delightful

amalgam of lush orchestration, and an antiquarianism jostling with Wagnerianisms

to particularly glistening effect (via those Russian horns). The sound

is splintery post War and boxy, quite raw and one dimensional without

spatial depth - but you won’t find it oppressive. The introduction is

full of incipient fantasy (horns joined by harp, setting up intimations

of Rusalka – Rimsky of course had dealt with the myth earlier

in May Night) and some nestling percussion and burnished strings

cultivated by Golovanov’s energetic, bristling baton. Of the singers

Kulagina is strong if strident, Pontryagin has a prominent tenorial

vibrato – though these seem not inappropriate given the slashing viola

support and blazing Scheherazade orchestration of their opening

scene in which Natalya Kulagina’s Solokha meets Pontryagin’s Devil.

Both basses are sonorous in the authentic Russian tradition and play

off each other well but Dmitri Tarkhov as Vakula opens somewhat weakly

with an indistinct head voice and a bleat lower down. But he develops

a lyric ardour later on with real Slavic bite and proves himself an

increasingly credible presence in an opera not bristling with much dramatic

tension and life; in fact it’s more of a tableau with minimal characterisation

and little motivic development, living instead through delightful morceaux

and a sense of the unreal for its vivacious life.

I enjoyed bass Sergei Krasovsky’s bleak black parlando

in his meeting with Tarkhov as I did the following piquancies of the

writing for flute and the elfin impress of the Second Scene in the First

Act (Rimsky seemingly taking delight in juxtapositions of tension and

orchestration). Whether you will swoon at the sound of the venerable

Natalya Shpiller rather depends on your tolerance level for Slavic Soprano

Wobble – but she’s certainly got plenty of range and dramatic projection.

As befits a work of this kind, where anvil and balladry are never far

away, Vakula’s song in the Second Scene is full of delightful folk inflexions

and the chattering and vigorous skittering of the Young Maidens who

end the Act is conveyed with no little vigour under the sweeping arm

of that maestro of monumentality, Nikolai Golovanov.

There are of course many other incidental – if uneven

– pleasures; Sergei Migay throws in a good act as the pompous Mayor

and the breathless clerk is tenor Sergei Streltsov, full of nasal insinuation

in his unaccompanied solo, a good touch. As the Fourth Scene of the

Second Act draws to a close we can hear again those Wagnerian motifs

and the driving, marching stridency and powerful direction that Golovanov

generates (in truth I sense he’s at his happiest in those moments of

orchestral reprieve where he can whip up band and choir into a dramatic

curve). As a pretty much static work – dramatically speaking – we get

more of the same; raw chilling trumpets, chattering wind, shrill choirs,

dance rhythms and folk inflexion. There’s a splendid role for the orchestral

leader in Act III and some blazing ferocity as the Act draws to a conclusion

– especially when the Devils get to work and when the Polonaise Chorus

begins to swirl. As the Tzarina, mezzo Ludmilla Legostayeva is introduced

with a novelty that hearkens back to the very opening orchestral introduction

– as befits her dignity and status Rimsky has her use a very old fashioned

and incongruous sounding operatic recitative. Her antique and timeless

measure thus established – and with the da capo work for choir as well

– and added to them the dark, rich tones of the Cossack chorus the work

threatens to come apart at the stylistic seams. Perhaps it does – who

cares when the Cossacks are having such stentorian fun. Elsewhere I

admired the extended scena for the soaring soprano Shpiller and the

orchestral leader, a virtuosic and attractive bit of scene painting

and the fine, incisive occasionally overwhelming contributions of chorus

and, not least, conductor.

With the limitations as noted, both in documentation

and recording – and also in terms of the work itself – this is so far

as I’m aware the only recording currently available (and I can’t vouch

that it’s in any way complete). I wasn’t converted to Rimsky’s musico-scenic

adventure but I enjoyed the sulphur and the rose petal along the way.

Jonathan Woolf