Written five years before his death, the Violin

Concerto was Ponce’s last major work. It has always been closely

associated with Henryk Szeryng, to whom it was dedicated and by

whom it was premiered. His recording of it was last available

on ASV CDDCA 952 and was first available on an HMV LP. This was

a fairly late recording by the sixty-six year old violinist and

his reflexes, and vibrato, have very slightly slowed although

it is still a strikingly successful performance. His hegemony

in the work was almost total and in fact dedicated Ponce-Szeryng

admirers can seek out other recordings made or taped over the

years. The first was with the Colonne Orchestra and Bour (the

premiere recording) made for Odeon. Others include a live Preludio

featuring the fiddler back on his native soil with the Polish

National under Krenz from 1958 and a Melodiya traversal with the

USSR State under Khaikin. The ASV is with the RPO and Bátiz,

made in June 1984, three years before Szeryng’s death. So much

for Szeryng. How about the Centaur newcomer?

Cuckson is an agile player with an attractive,

centre-of-the-note clarity. She brings reserves of technique and

lyrical elegance to the Ponce, a work that can appear – or maybe

is – diffusely eclectic, especially in the longish opening movement.

That said I’ve always loved the deeply lyrical second subject

over a pedal point – most attractive here – and the scurrying

but rather conventional passagework for the soloist. The tension

between the national and modernist idioms is never quite resolved,

but it is notable how well Ponce integrates native dance elements

into the fabric of the first movement. This is something for which

historically he has been given somewhat less than his due, I think.

There are occasional hints of Hindemith along the way as there

are, more rapturously, of Delius in the passage immediately before

the extensive cadenza. The triplet-insistent coda is well played

here – though surely the final bars are somewhat too grandiose,

more Ponce’s responsibility than the orchestra’s. As is well known

Ponce embeds his 1910 Greatest Hit, Estrellita, into the

second movement – fragmented, alluded to, half revealed. The notes

don’t discuss it but I was always under the impression that Estrellita,

like Elgar’s Salut d’amour, was one of those songs sold

cheaply to a publisher. If so the reminiscence takes on an ambiguous

air; memories of Ponce’s celebrated song, regret, bitterness?

Well, it certainly doesn’t sound bitter because this is soaringly

lyrical music, played with perhaps too much restraint here. The

Czech National sounds a bit earthbound. The finale is a Corrido

dance, impressionistically elegant, with some cool orchestration.

The winds can turn exotic but the strings remain discreet and

gradually the giocoso sprit pervades the whole band. This

is certainly an attractive reading – a little small-scaled and

with occasionally diffuse orchestral support.

Coupled with the Ponce is the Korngold, an unlikely

disc-mate I’d have thought but one written a couple of years after

the Ponce. I say ‘written’ but stitched, weaved, fashioned, edited,

compiled and elaborated would be better words to describe this

joyous if sinful confection. Not only is it an unusual choice

to accompany the Ponce but it owes its life and existence to an

equally unlikely begetter – not Heifetz, as many think, but none

other than the arch Philosopher of the violin, proposed architect

of Pan-Europeanism as a political concept, the youth who played

to Brahms, Bronislaw Huberman. It wasn’t Huberman who premiered

it – that was Heifetz, whose recording still holds sway

and who reveled in its glittering virtuosity and vocality, its

glorious lyricism and surging drama. You can find much, though

not all, in this performance. She stresses the chaste lyricism

at the heart of the Romance (with its Anthony Adverse

Straussisms) and is bracingly attentive in the Finale. She must

yield to others in matters of tonal effulgence but otherwise this

is a winning performance. Indeed this is an attractive if, again,

unusual coupling of two mid-century works that embody entirely

differing musical aesthetics to make their points.

Jonathan Woolf

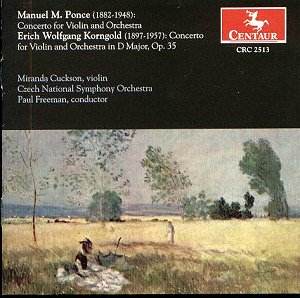

![]() Miranda Cuckson (violin)

Miranda Cuckson (violin)

![]() CENTAUR CRC 2513 [57.

52]

CENTAUR CRC 2513 [57.

52]