Petri was in his youth something of a multi-instrumentalist.

We remember him as Busoni’s greatest pupil and a Lisztian of coruscating

brilliance but he was also a violinist – not surprising as his

father, Henri, was an internationally renowned performer and teacher

– but also, less predictably, as a French horn player good enough

to take a place in the Dresden Symphony. Petri was a musician

of the utmost clarity, distinction and directness with a technique

remarkable even into old age and whose conception of space and

tonal value gave him a persuasive insight into music of intellect

and weight. As a Beethovenian he was distinguished - as a Chopin

player he maybe reflected something of his teacher Busoni’s own

professed ambiguity and duality of response. Petri’s pre-War Columbias

have been collated on APR and demonstrate his strengths in abundance.

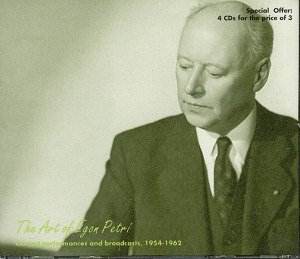

Music and Arts has here brought together his concerts and broadcasts

from the period covering 1954 to 1962, the year of his death.

His reluctance to travel, his physical lack of flamboyance, indeed

his active distaste of extravagance and extraneous gesture and

detail, meant that audiences didn’t much clamour to hear him.

Their loss is evident from this uneven but nevertheless exceptionally

significant series of survivals.

There’s a caveat to be made about the actual

piano sound on some of these off-air and private recordings; it

can be rather harsh but it’s not at all unlistenable. There are

also some imperfections to be expected – some wow and distortion

(minimal and fleeting) some dropouts (ditto) as well as pitch

distortion. These are all honestly noted in Music and Arts documentation

and I should mention them here; they didn’t unduly trouble me.

The repertoire is very much Petri’s canonical one – the last Beethoven

sonatas, Busoni, Chopin as well as Bach-Busoni and Bach-Petri.

He was always a charming exponent of Gluck, a more unexpected

one here of Medtner. Of Liszt there’s but a fleeting glimpse –

Venezia e Napoli, taped in the last year of his life.

We start with his Chopin Preludes Op. 28. Well,

best to get this over with I suppose. I find his Chopin rather

disappointing. His rubati in the Agitato opener are well judged

if unexceptionable (he was known to scorn the emotive exaggerations

of some of his colleagues) but he is very, very cool in No. 4,

the Largo in E. There’s a dispassionate control in No. 6, a Lento

from which, however, he seems to wish to expunge feeling. He is

fine though in another Largo, No. 9 in E – his truly noble sound

is affecting – but there isn’t enough distinction between the

hands in No. 11, where he fails to differentiate the melody line

in the right hand. There’s even a distribution between hands –

something that seems to me afflicts No. 13 in F sharp as well.

The Sostenuto in D flat (No. 15) is very dry playing indeed –

Petri adamantine in his refusal to indulge colouristic potential;

in addition his left hand covers the right at some crucial moments.

He improves considerably for the B flat Presto and the power contained

within as he does for the virility and energy of the Allegro appassionato

conclusion (he omits Nos. 21 and 22 for some reason). Throughout

I felt him most comfortable with the athletic, technical side

of the Preludes and rather less indulgent towards the lyrical

side that Busoni himself felt most ambivalent about. Of his Busoni

indeed I could hardly say anything other than that it is magnificent.

The Song of Victory from the Indian Diary is 1.16 of powerfully

sustained pianism of an exalted level whilst the eloquence of

the Bluebird Song shows that what he failed to do so glaringly

in Chopin he could manifestly do in Busoni. The final dance shows

off Petri’s superb rhythmic control, his colour and his sheer

depth of tone (never overdone). He was seventy-seven when he was

taped in Busoni’s All’Italia – sheer virtuosic panache. The disc

finishes with twenty-five minutes of Petri with the eminent pianist

Carlo Bussotti in a stratospherically impressive Fantasia Contrappuntistica;

the two men seemingly joined at the musical hip so intense and

marshalled their decisive vision.

The second disc is rather more bits and pieces

– but what bits what pieces. The Medtner is very

impressive playing indeed if not quite in the Moiseiwitsch or

Medtner class. The Danza Festiva is rather heavier than the composer’s

own recording but the Op. 20/2 Fairy Tale in B has some seismic

attacks. The Schumann Fantasiestücke are in somewhat splintery

sound but he plays them with rather more overt affection than

he did the Chopin; the Allegro con fuoco second is sonorous, the

third is affecting, without affectation, and the Vivacissimo,

Dream Visions is full of filigree drive, albeit one accompanied

by a degree of tape distortion. His own Bach Chorale arrangements

are justly famous as are his recordings of them. Sheep may safely

graze is nourishingly intimate and beautifully adept with its

sudden pianissimi, whilst I step before Thy Throne grows in authority

and grandeur. There’s little real difference between Petri’s 1930s

recording of the Minuet (from the W.F. Bach Notebook) and this

one, made in 1958. His Schubert-Liszt is duly frolicsome and the

Nocturne in D flat has quite a lot more vivacity and colour than

he lavished on the Préludes, albeit his rhythm is rather

heavy.

The third disc gives us his trademark Gluck-Sgambati

Melodie – and this time he must cede to his earlier self; he’s

heavier, more emphatic, less treble oriented preferring to concentrate

instead on the middle voicings. The captivating beauty of that

earlier recording has been replaced by a philosophic depth that

does seem rather alien to it. His Beethoven Op. 90 Sonata is characteristically

plain speaking and strong; the second of the two movements is

especially buoyant and decisive. The Chopin examples here, the

Sonata in B and the Nocturne in F sharp, are vitiated by choppy

rhythm. Petri was seventy-eight when these performances were taped

so maybe that has something to do with it but whilst there are

tonally delightful glints in the opening Allegro of the Sonata

it sounds as if, like a mathematician, Petri were actively breaking

the movement – and indeed the work as a whole – into units. The

algebraic-philosophic-contrapuntalist approach here renders much

of this very disappointing. I liked the lento much more though

and whilst the presto finale again suffers from rhythmic insistence

there are still compensatory features of colour and vivacity.

The final disc is in many ways the most consistently

elevated in musical terms, principally because it finds Petri

addressing Beethoven. There are some technical frailties in the

opening of Op. 109, it’s true, but more important by far is the

sense of powerful direction. Again the tiny Prestissimo second

movement taxes him for a moment but we should concentrate on the

Andante finale. Here Petri is very direct, almost casual, but

as the movement advances and his architectural priorities become

clearer we are aware of a mind of illuminating integrity at work.

By the later variations he develops a degree of metrical flexibility

that one would not have earlier suspected. There is no undue sentiment

and I would certainly understand those who hold this to be a logician’s

Beethoven. My own instincts are for something more overtly expressive

but I can but admire the tremendous concentration of his approach.

The A flat Sonata, Op. 110, again taped in 1954, certainly lacks

to my ears the molto espressivo in the first movement requested

of the performer. But Petri is careful to reserve the weight of

his intelligence and tonal resources for the first, Adagio section

of the finale. He keeps this moving with an almost Arietta delicacy,

though he certainly employs weight and shading. The Fuga is strong

and determined. In Op. 111 his Maestoso is fast, strong, with

no great tonal beauty to it. I have to say I found it inflexible,

on one level and rather superficial. It’s a performance that seeks

to divide and fracture still further, rather than reconcile, the

character of both movements. With a pianist such as Solomon the

seemingly disparate and oppositional movements take on congruence

and a retrospective sense of rightness. With Petri the implacably

oppositional nature of the Sonata is starkly delineated. In that

Arietta finale Petri is flexible without coming to a stop; his

syncopated passages are driving, even a little peremptory, but

he never seeks to extract huge weight of left hand tone or to

indulge abstraction. This is intelligent, lean, technically adept

and impressive playing, whatever ones view of its ability to move,

which I happen to find relatively limited.

Documentation consists in the main of an interview

between annotator Frederick Maroth and Petri’s English pupil,

Claire James who had attended the famous Busoni-Petri two-piano

London recital of 1921. They deal with the central features of

Petri’s pianism with acumen, as one would expect, with some quietly

revealing information disclosed along the way. This is a set of

some real importance in capturing Petri’s art at a time when he

was given considerably less than his due. Even at his most phlegmatic

his brand of musical stoicism added an imperishable page to the

annals of pianism on record in the twentieth century.

Jonathan Woolf