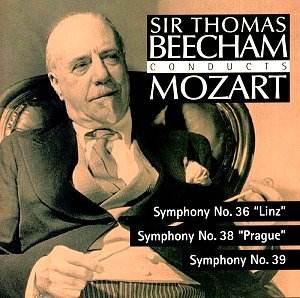

"Nothing from Moh-zart?" Beechamís

quip enquiring as to missing telegrams at his 80th

birthday celebration is one side of his waggish drollery. The

recorded evidence of his Mozart recordings in the 1950s Ė how

he relished the Edwardian splitting of the composerís name into

two evenly drawled parts Ė was a matter of increasing debate.

I find that the binary reputation that has persisted - pre-war

pretty good, post-war badly affected Ė tells only a partial story,

though its broad outline seems to me clearly true. Of the three

symphonies the E flat major receives a spacious but consistently

elevated, though not unproblematic, performance, the Linz a

vigorous one full of affectionate detail and the Prague

one that sometimes exposes Beechamís increasingly manicured phrasing

to some detrimental effect.

Firstly, the sound of the recordings; at this

period a rather resonant acoustic perspective was favoured for

Beechamís symphonic discs and that is of course mirrored in these

transfers. This does lead to a blunting of attacks from time to

time and a general weighty spirit prevails, not inappropriately

so given Beechamís considered affection for the works. The phrasing

in the adagio introduction to the Linz is affection itself

though the tempo is considerably slower than one would expect

now, a fact that is an irrelevance so far as Iím concerned, but

which might trouble those who constantly relate historical performance

practice to current notions or conventions. The full complement

of the RPO strings sound to be on show but, even so, telling wind

detail emerges, though not with quite the immediacy of other more

lissom readings. The Andante is songful and lyrical and is tinged

with a perceptible feeling of loss whilst the Presto finale is

bluffly vigorous and full of dynamic terracing and subtlety of

texture.

The Prague opens once more with affectionate

delicacy but here, in the earliest recorded of the trio, in 1950,

the details sounds unduly mannered. The self-consciously polished

phrasing of the initial Adagio precludes real depth and the lead

into the Allegro sounds especially artful. Once there, brio does

have its welcome place, but Beechamís preoccupation with texture

building and over emphases of various kinds negate much of the

virtuosity and intelligence of the music making. The Andante is

nicely flowing but again somewhat too often visited by inflection;

the finale is fine.

The E flat major has about it a greater weight

of concentration in this performance, albeit one accompanied by

emotive string crises, laden with depth of tone. Phrasing is strongly

romanticised, emphasis sometimes on detail Ė the sound not as

buoyant and aerated - surprisingly this applies to the strings

- as one might want. But there is to compensate, plenty of inner

part detail and a sense of cohesive direction. The slow movement

is lyrically phrased without undue exaggeration, though there

is a degree of it still, and the Minuet is one of Beechamís pomposo

treats. In the finale his fine little crescendi make their mark,

as does some somewhat unnatural sounding woodwind spotlighting

Ė otherwise this is avuncular, buoyant, subtle music making.

My own preference is for Beechamís pre-war recordings

with the LPO, which are more lithe and bristle with vigour and

sensitivity. Nevertheless these later traversals carry the inimitable

stamp of authority and there is much still to admire.

Jonathan Woolf