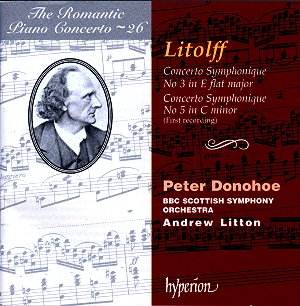

The listening public owes Hyperion a huge debt for

the series, 'The Romantic Piano Concerto,' of which the present issue

represents Volume 11. Litolff has been seen as even less than a one-work

composer - only one movement, the Scherzo from the Concerto symphonique

No. 4, has retained a hold on the repertoire, extracting notable interpretations

from Curzon, Cherkassky and Ogdon. The present recording represents

the only available recording of No. 2, and the only complete one of

No. 4; there is also an account of No. 3 in E flat, Op. 45 (c1846) by

Ponti on Vox.

Litolff was a student of Moscheles. He sits firmly

in the tradition of the performer-composer, helping to form a link between

the Classical and Romantic periods. He added an 'extra' movement to

his inherited concerto model, inserting a Scherzo between first movement

and slow movement. His five Concertos symphoniques sometimes

feel more in the mode of a symphony with piano obbligato (the piano

part is always virtuoso), although the pronounced lyricism of the Andante

of No. 2 leaves no doubt as to the piano's solo role. This movement,

in fact, captures Donohoe at his best: entirely in style and completely

convincing. There are, however, some hints towards Donohoe's propensity

to 'bang' the piano (i.e. to not give an appropriate fullness of tone

to passages above forte).

The Second Concerto dates from 1844. The orchestral

contribution is notable for being lyrical but with momentum: Litton

commendably does not allow over-sentimentality. It has to be said that

the orchestra sounds substantially more involved than Donohoe, who seems

to be always at one remove (despite the high quality of his filigree

and overall dexterity). Donohoe is actually at his best in the Allegretto

rondo-finale, with its playful and jaunty dance-like theme. He has no

problems with the strong virtuoso element of this movement.

Again, Donohoe is not quite up to the free-flowing

lyricism of the first movement of No. 4; and he fails to capture the

element of fantasy inherent in this music. That said, the Lisztian opening

gestures are well brought off, and the dramatic argument of the movement

remains intact. The orchestra excel themselves.

The famous Scherzo brings neat playing from Donohoe,

and a fair amount of panache towards the end, but here the element of

fun is the crucial missing piece to this jigsaw. The piano sounds uncomfortably

close in the Adagio religioso, and above mezzo-forte the legato appears

strained: it is only in the finale (Allegro impetuoso) that Donohoe

seems to fully let his hair down. Ironically, it is the orchestra (who

up until this point had been excellent), that lets the movement down

with scrappy string playing.

Worth hearing for the repertoire, certainly, even if

the overall impression is that of a 'near miss'.

Colin Clarke