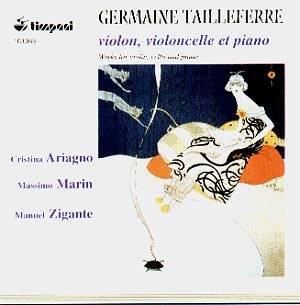

This disc brings together works for strings and piano

written between 1913 and 1978 by Germaine Tailleferre. What is remarkable

is the consonance and continuity of technique and expression between

the two extremes, which leads to the reflection that far from "not

developing" in the broadest most concentrated sense Tailleferre

grew to simplify her style but not to divert from its essential core.

Returning, for example, sixty years later to the Trio she had written

in 1917 she remains imaginatively the same composer when she added two

movements to it, movements both sympathetic to and enriching of the

originals. Write Tailleferre off at your peril.

That Trio, composed between 1916 and 1917, opens in

the Gallic hot house with an Allegro animato of richness and

density. The subsequently composed Allegro vivace (from 1978)

is animated and stomping with a vein of wit and a slight antique air

in the aloofly Ravelian mode whilst the third movement Moderato

dates from 1917 and is brief and slight. The finale opens harmoniously

before gathering some momentum - a strong work from 1978. As a pendant

the original 1917 second movement is presented; fleeting like gauze,

flickering but securely anchored by the cello you will reach for the

usual suspects of influence but I found it a subtle movement well deserving

its disinterment. At 538 it would formally and structurally, I suppose,

be said to unbalance the Trio, which in this composite form lasts only

13 and a half minutes. Nevertheless a slice of the muslin Tailleferre.

Her two violin sonatas have been recorded a number

of times before Renata Eggebrecht and Gassenhuber most recently on

Troubadisc TRO-CD 0406, also fearless champions of Ethel Smyth, but

also by Ehrlich and Eckert on Cambria; the Second Sonata has also been

recorded by Arnold Steinhardt and by Roche and Fried on Vox. The First

Sonata of 1921 opens sunnily but a rather more pensive and inward second

subject steals in darkening the mood. The Sonata was written for and

dedicated to Jacques Thibaud and he premiered it with Cortot in June

1922. The work clearly also carries within it an autobiographical charge

because of the relationship between violinist a suave womaniser

and composer. The rhythmically amusing piano writing of the second movement

scherzo runs beneath a lyrical violin line, some teasing little battles

between the two lending a flirtatious air to the movement whilst the

slow movement is dominated by the piano initially before the violin,

musing reflectedly at first begins a more passionate series of episodes.

In the finale there is more of a sense of consonance and solidarity

between violin and piano until the closing moments with a long held

note from the violin and the pianos strange unsettledness beneath until,

just in time, the violin perks up, the piano with it, for a little dance

tune to end the work.

The Second Sonata was derived from the Violin Concerto

of 1936, which was premiered by Yvonne Astruc and Pierre Monteux. Milhaud

liked it and was a known admirer of the violinist who had also premiered

his own work. Tailleferre revised the Concerto for violin and piano

for performance in 1946 and it was subsequently performed by Jeanne

Gautier the notes anglicise her name as Jane and Tailleferre herself

in 1951. Delightfully full of fresh air and uncomplicated the first

movement is avuncular and openhearted and the finale charmingly motoric

with room for quick light trills from violinist Massimo Zigante. The

Sonatine equally has a joyful freshness tinged with moments of

reserve, a light breeze of a work. Elsewhere the early Berceuse

shows her indebtedness to Fauré; the Adagio is a transcription

of her Piano Concerto an affectionately serious movement. The Pastorale

is a rocking, romantic work with an unexpectedly late Romantic profile.

Idiomatic and understanding these performances do Tailleferre

proud. They catch something of her elfin pleasure and also a touching

reserve. Its not surely necessary now to liberate her from the constrictive

notoriety of membership of Les Six; on her own terms she was a lyricist

and romantic, inheritor of Faurés gift for melody but tinged

by her modernist inclinations, and here a composer of still treasurable

generosity.

Jonathan Woolf