In many respects Schumann is the archetypal romantic

artist: deeply influenced by literature, committed to powerfully intense

emotions, creatively aware of the virtuosity of performers. He was himself

a fine pianist, and the first twenty-three of his published compositions

were for his own instrument. His marriage to Clara Wieck in 1840 coincided

with a new phase in his creative life, concentrating on song, for in

that year alone he composed some 140 lieder. Then two years later chamber

music became his priority, with three string quartets, and a piano quartet

and quintet, the latter one of the finest examples of the genre.

Schumann also wrote four fine symphonies and three

concertos, one each for the cello, the violin and the piano, as well

as choral music and two works for the theatre. But the man himself remains

something of an enigma, a depressive whose mental anguish resulted in

1852 in a failed suicide attempt, and incarceration in an asylum for

the last two years of his tragically short life. Much of his output

is little known, but there is no doubt that Schumann was one of the

key figures of the romantic movement and one of the great composers

of the 19th century.

Schumann was not fully at home with opera, despite

the excellent music to be found in his Genoveva. The Scenes

from Goethe's Faust has its operatic qualities, to be sure, but

like Berlioz's Damnation of Faust, it occupies a hybrid position

and is more at home in the concert hall, a kind of dramatic oratorio.

Schumann composed the work for the celebrations of

the Goethe centenary in 1849, although not all of it was complete in

time. It is no surprise that there were such difficulties, since the

music is constructed on an extended scale and composed with great attention

to detail. Here the symphonist and the song writer really do come together,

and the responses to the text and the drama are intensely felt.

Parts 1 and 2 contain portraits and other aspects of

Faust and Gretchen, whereas Part 3 (like the final part of Mahler's

8th Symphony) is concerned with Transfiguration. There are changes of

style and approach as suggested by this epic scheme, but no matter.

For this is a committed and visionary work which contains some of the

best music Schumann ever composed, not least because for him it was

a labour of love.

For example, he wrote nothing more dramatic than the

scene depicting the blinding and death of Faust. Moreover, after hearing

this, who dare suggest that Schumann was a poor orchestrator?

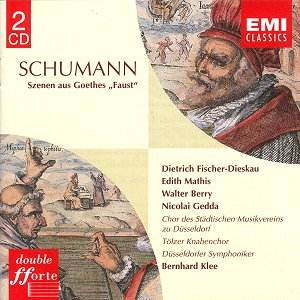

Bernhard Klee conducts a performance of vivid conviction

and drama, though the visionary aspect which comes to the fore in Part

3 is appropriately lyrical in tone. Of the singers, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

takes the leading role, as he did also in the recording conducted by

Benjamin Britten (on Decca). It is a tribute to his artistry that he

is equally successful as Faust and, in Part 3, as Doctor Marianus. In

truth there is a distinguished and particularly strong team of soloists

in this performance: Walter Berry, Edith Mathis, Nicolai Gedda are all

at the peak of their form. With very good, truthful recorded sound and

high production standards, this recording still gives enormous satisfaction

twenty years after it was made.

Terry Barfoot